Robert Schumann (1810-1856)

Carnaval, Op.9 (1834-1835)

Arabesque, Op.18 – Prélude (1839)

Clara Wieck-Schumann (1819-1896)

Soirées musicales, Op.6, No.2 Notturno – Prélude (1836)

Franz Liszt (1811-1886)

Sonata in B minor, S178 (1852-1853)

Prélude – Consolation No.3 in D flat major, S172 (1849-1850)

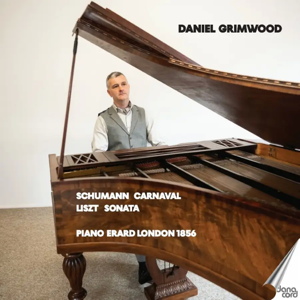

Daniel Grimwood (piano)

rec. 2024, Sir Jack Lyons Concert Hall, York, UK

Danacord DACOCD986 [75]

Erard pianos have always been highly regarded. Sébastien Érard founded the company in Paris in the late 18th century. The instruments were popular with many composers, among them Liszt, Mendelssohn and Hummel. The pianos were known for their powerful tone, with complex overtones. The present instrument, made in 1856 by Erard London, is housed in York University’s School of Music Performance. In this recital, it is tuned in unequal temperament. (Equal temperament divides the octave into twelve equal parts, which allows consistent tuning across all keys. Unequal temperament varies the tuning, favouring certain keys for richer harmonies. Each has its unique sound and character which influence the music’s emotional expression and historical development.)

The sound of this piano could be summarised as intimate and nuanced in the quieter moments, but equally capable of making powerful, dramatic statements. Another remarkable facet was the incisive tone in the concluding fugato passage of the Liszt Sonata.

I wondered if I would enjoy Schumann’s Carnaval played on a period instrument. This captivating suite of twenty-one short piano pieces posits personalities at a masked ball in the Venetian carnival season. Schumann introduces characters fictional and actual. There are offerings to his future wife Clara Wieck, Chopin and Paganini. Estrella is Ernestine von Fricken, who at that time was Schumann’s secretly engaged fiancée. Then there are figures from the commedia dell’arte, such as Arlequin, Pantalon and Colombine, and Pierrot. There are the important Eusebius and Florestan, Schumann’s alter egos: the former represents the tempestuous side of his character, the latter the reflective side. Then there are the unplayed Sphinxes or cryptograms which provide a “sense of unity amongst the seemingly disparate musical aphorisms”. They ‘spell out’ Asch, Ernestine’s birthplace. Carnaval concludes with the splendid Marche des “Davidsbündler” contre les Philistins, which represents “the eternal battle between the outmoded and the new”.

Any performance of Carnaval must balance whimsy, imagination and sheer hedonism opposed to introspection. I had my misplaced misgivings about Daniel Grimwood’s use of the Erard London 1856: he has created a satisfying account. As it unfolds dizzyingly, he holds the disparate sections in a cohesive whole.

When Schumann resided in Vienna, separated from Clara save by letters, he wrote three important works: the Arabesque, Op.18, the Blumenstück, Op.19 and the Humoreske, Op.20. We hear the first of the three. It is a modified rondo, with a memorable principal theme and two episodes in the minor key, one stormy and the other oppressive. Unusually, the piece ends with a quiet epilogue of “pristine beauty”.

Clara Wieck-Schumann’s Soirées musicales was one of a set of six written when she was only sixteen or seventeen years old. They were influenced by Schumann and Chopin. The second number of the set, Notturno, is quite lovely: a simple tune with some remarkable decoration and varied accompaniment, at times chordal, typically arpeggiated.

Much has been penned about Liszt’s Piano Sonata. Most famously, Richard Wagner said: “The Sonata is beyond all conception, beautifully great, lovely, deep, and noble – sublime.” Liszt dedicated it to Robert Schumann. It is ostensibly in a single movement but encompasses the traditional four movements. The unity is derived from a small set of themes subject to constant transformation as the piece develops. Although there is no programme, it has been suggested that the Faust legend may have been in Liszt’s mind.

This massive work requires unbelievable technical skill and stamina. Equally important is the interpretation which should cover a wide range: there is drama, power, tenderness and love. It has been said that there is “virtually every emotion known to humankind in these pages.”

There is an eye-watering number of recordings of the Sonata. Great masters have presented their interpretations to the world: let me only mention Martha Argerich, Daniel Barenboim, Emil Gilels, Van Cliburn and Vladimir Horowitz. I was again a little skeptical at first, but I cannot fault Daniel Grimwood’s powerful and unified performance on the London Erard. It would not be my first choice for listening, but it makes a refreshing change to the modern concert grand.

Liszt’s second version of six Consolations remains amongst his most popular piano works. No.3 is really a Nocturne, clearly inspired by Irish composer John Field, whom Liszt much admired. The piece is gentle and lyrical, with a lovely melody supported by delicate arpeggios; it ends with a short cadenza and a ppp close. It sounds well on the Erard.

In three of these works, the recitalist has adopted the old practice of improvising a Prelude before beginning to play the work proper. It is not helpful. The pieces are designed to be stand-alone or part of a set, and do not need any introduction to prepare the listener’s mood.

Daniel Grimwood is noted for his performances of 19th-century virtuosic piano repertoire, particularly the music of the German composer Adolph von Henselt. He has performed at significant venues worldwide, including the Wigmore Hall and Symphony Hall in Birmingham, as well as venues in Europe, Egypt, Lebanon, Oman and Australia. Grimwood is a Research Associate at the University of York, specialising in 19th-century performance practice. For enthusiasts of British music, his recording of Doreen Carwithen and William Alwyn’s piano music (Edition Peters, EPS007, 2019) was well received by The Gramophone and the BBC Music Magazine.

The helpful liner notes give a good introduction to the music, and the information about the piano and performance aesthetics. The recording is splendid.

As I noted, historic pianos would not be my preferred choice for listening to this repertoire. Nonetheless, it was a fascinating experience to hear Carnaval and Liszt’s Sonata played on an instrument that would have been more or less contemporary with the music.

John France

Buying this recording via the link below generates revenue for MWI, which helps the site remain free.