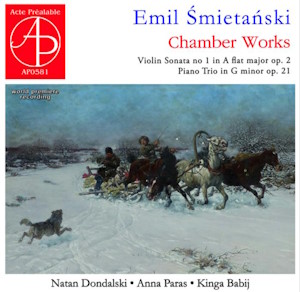

Emil Śmietański (1845-1886)

Violin Sonata No. 1 in A flat major, Op. 2

Piano Trio in G minor Op. 21 (1867)

Natan Dondalski (violin), Anna Paras (piano), Kinga Babij (cello)

rec. 2023, Studio Czesław Niemen, Polish Radio, Koszalin, Poland

Acte Préalable AP0581 [46]

Acte Préalable proprietor Jan Jarnicki continues his endless quest to shed light on the most inaccessible recesses of bygone Polish music with the label’s first release of works by Emil Śmietański whose brief life ended abruptly in a train crash in Mödling, near Vienna in 1886. Śmietański’s obscurity is reinforced both by the brevity of his biography in the booklet and by the wry, revealing yarn Jarnicki spins regarding his unsuccessful attempts to access scores of this composer’s music from the library of the Warsaw Music Society directly after hearing the trio recorded here at a recital in the early 2000s. By all accounts the management of this organisation were extraordinarily precious regarding access to scores for those perceived as outsiders at that time; the moment passed and not unreasonably Jarnicki moved on and directed his curiosity towards other forgotten Poles. A quarter of a century later the Acte Préalable catalogue boasts a tally of just shy of 600 titles, a fact which reveals much about Jarnicki’s extraordinarily dogged commitment to the cause of Polish music.

In any case he never completely forgot Emil Śmietański and was thus astonished many years later to find that the Warsaw Music Society’s entire archive of scores had apparently been digitised and made accessible to the public. Jarnicki was thus able to rescue that elusive trio as well as an early violin sonata with which it is coupled on this new disc. He has unfortunately been unable to trace any other scores of chamber music by Śmietański, despite his apparent reputation as a prolific composer. This accounts for the disc’s relatively brief playing time.

To summarise the salient biographical points from Karol Rzepecki’s booklet portrait of the composer, Emil Śmietański was born in Tarnów, schooled in Kraków and studied piano (and presumably composition) in Vienna during the early 1860s. At some point in the latter part of this decade he returned to Kraków where he taught piano and performed as a celebrated local virtuoso. His burgeoning reputation led to concerts across Poland, Germany and Austria and Śmietański even premiered Robert Fuchs’ B flat minor piano concerto in 1880. He evidently composed until his untimely demise.

The question, as ever, is whether Śmietański’s output is worthy of preservation. At my first hearing of his Piano Trio Op 21 I could certainly discern why Jan Jarnicki was immediately taken by this music. It is really difficult to place it, or to relate it to any obvious stylistic fingerprints of Śmietański’s more celebrated peers and contemporaries. A rather chromatic and richly textured introduction actually seems to anticipate Szymanowski – the booklet describes the Allegro molto that ensues as ‘exuberant’ – it is anything but. It is Slavic, impassioned but somehow repressed. The fluency of its utterance seems to conceal something mysterious and complex. There are plenty of moody tremolandi for all three players. The word ‘plodding’ may seem a bit loaded but in this case it aptly characterises the pace of the piece. The melodic content is strangely elusive but stubbornly memorable with repetition. I do get the sense that all three players find Śmietański’s style rather unusual and at times they seem to be struggling for unanimity, but all in all the performance is decent and the sonics serviceable. The central Larghetto is most obviously song-like in the violin’s long, soaring melodic lines, but the overall mood Śmietański projects seems to be a continuation of that which prevailed in the first movement. The slower section towards the conclusion of the movement seems in danger of sagging but is just about rescued by the violinist’s octave jumps. The Presto finale employs an earthy, lively Slavic dance style, but intermittent episodes are as ambiguous, if not quite as troubled as the content of the first two movements.

I really liked Śmietański’s trio. It doesn’t really seem to fit the era of its provenance, yet it somehow hangs together against the odds. Ultimately the playing here just about carries the work but I wouldn’t be surprised if fellow listeners felt that the performers would have benefitted from considerably more rehearsal time before committing this recording to posterity. I can’t help thinking that there’s actually a really interesting, unusual work here – one that’s worthy of much more studied investigation. I heartily encourage readers to try it.

Śmietański’s Violin Sonata in A flat, Op 2 which opens the disc is an apprentice work, and not unexpectedly incorporates a more traditional classically informed four movement structure. Its first movement, marked Allegro assai, is the most substantial in terms of duration but its dimensions seem too grand for its material. The Beethovenian theme introduced by the piano is certainly catchy and even elegant; it’s developed with some vigour by the violin although its vernal promise peters out rather swiftly. It’s as though Śmietański doesn’t quite know what to do with it. Both elements are blended in a minor key central section which seems equally perfunctory before the main theme returns for the coda. The slow movement is wistful and rather doleful – the piano projects the more interesting melodic content whilst the reliance on repeated note patterns in the violin part seems as effortful for Natan Dondalski as it proved for this listener. At least the pair of swift movements which conclude the sonata more than hold the listener’s interest. The third is a delightful Scherzo whose main idea owes something to Schubert. The Presto finale is equally attractive, the violin colourfully imitating the piano’s lead as the movement proceeds. Both these movements display a palpable confidence in Śmietański’s writing which provides a refreshing and memorable counterpoint to the tentativeness and uncertainty which hinder their predecessors.

The performances by what appears to be a scratch trio of stalwarts from the Polish chamber music scene are solid and whole-hearted although the unfamiliarity of the music (and the sheer awkwardness of the first half of the sonata) reinforce my view that considerably more rehearsal time would have benefitted both pieces. The Acte Préalable sonics are commendable in the main, although some of the thicker textures in the trio seem a little cluttered – to the disadvantage especially of the cellist Kinga Babij. The documentation proves to be somewhat eccentric, at least in terms of the English translation; notwithstanding Jan Jarnicki’s fascinating insight into the politics of administering Poland’s musical archives, Karol Rzepecki’s analysis of the two works themselves seems superficial and repetitive.

As for Śmietański’s music the trio seems surprisingly adventurous for 1867 and has certainly piqued this reviewer’s curiosity regarding the music he produced in the last two decades of his life. It’s not the first time Acte Préalable and their indefatigable CEO have unearthed forgotten repertoire of uncommon interest – folk with an insatiable curiosity for genuinely unknown figures like Emil Śmietański have countless reasons to be grateful to Mr Jarnicki.

Richard Hanlon

Availability: Clic Musique!