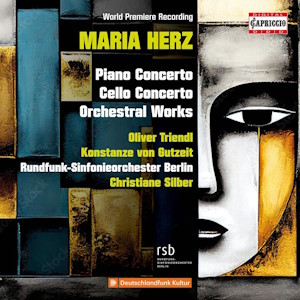

Maria Herz (1878-1950)

Piano Concerto, Op 4

Four Short Orchestral Pieces for Large Orchestra, Op 8 (1928)

Cello Concerto, Op 10

Orchestral Suite, Op 13 (1932)

Oliver Treindl (piano), Konstanze von Gutzeit (cello), Rundfunk-Sinfonieorchester Berlin/Christiane Silber

rec. 2022/23, RBB, Saal 1, Berlin, Germany

Capriccio C5510 [81]

Maria Herz studied with Max Pauer, a pupil of Mozart’s son Franz Xaver. In her twenties, she moved from Cologne to Manchester with her chemist husband, with whom she had four children. Moving back to Germany in 1914 just before the outbreak of war, she remained there, surviving her husband’s death in 1920, bringing up her children and then taking composition lessons with Philipp Jarnach. A small amount of success came to her in the later 1920s when her Four Orchestral Pieces, Op.8 – performed in this disc – were premiered by Hermann Abendroth. Despite this, few of her works were published and, in the worsening political climate of the early 1930s she moved back to England. After the end of the war, she went to America to join one of her daughters, where she died in 1950.

Capriccio surveys her work chronologically and though it seems impossible to locate the exact date of composition of a number of them a rough guess would put her Piano Concerto as somewhere around 1926. This is an intriguingly angular work, a battle of wits between piano and orchestra, in which the piano increasingly tries to unshackle itself of the orchestra’s inhospitable attentions via some rhapsodic and fast-running decorations, mixed with stern chording and delicate tracery. Toward the end of a relatively long first movement – 14 minutes – the orchestra reasserts its authority. The central movement casts a languorous spell, from the piano chimes and reflective soliloquizing to the lyricism of the cor anglais. Terse brass figures introduce the finale which contrasts with a kind of elvish stomping, the music moving between extreme states whilst the piano puckishly plays off the glowering orchestral forces, gradually asserting itself in a braggadocio-like peroration. What an unexpected and interestingly conceived concerto from a virtually unknown composer.

The Orchestral Pieces, Op.8 espouse a toughly-hewn late-Romanticism and owe something to Reger and Schreker, perhaps. They’re well characterised, and include nocturne-like elements as well as sinewy, powerful dissonance. One can see that a work as sharply defined and athletic as this would have interested someone like Abendroth. The Cello Concerto, Op.10 is her most overtly Jewish work. Its clotted cello ascent and dour orchestration may be initially forbidding but it’s clear that the music plays out questions of striving, and seemingly failing, to reach a natural harmonic resolution. It’s only when a Mahlerian gong is heard and a freilach breaks out that the music dances wildly for a while, the cello’s ascending line accompanied by a melange of orchestral colour, notably high winds – the cello concerto is a tricky beast to balance sonically – before a fugato swiftly brings the revels to a close.

The Orchestral Suite, Op.13 dates from 1932 and is cast in six movements – four brief and two in excess of four minutes. There’s a richly-voiced chorale, a kind of tango, some neo-classicism, and a rip-roaring, brassy fugue.

A word about the performers, then. Pianist Oliver Triendl must play a previously unknown piano work every week. He has an impossibly fecund discography and plays the Concerto with all his accustomed nuance and stylistic acumen. Konstanze von Gutzeit has a rather less extrovert vehicle with which to work but manages to convey its dualities very well. She’s the cello principal of the Rundfunk-Sinfonieorchester Berlin which plays splendidly throughout under Christiane Silber.

No complaints about the well-judged recorded sound or the notes, which are mildly and engagingly quixotic, and biographically helpful.

These are all world premiere recordings, it would seem – note the critic hedging his bets. That’s Capriccio’s claim at any rate. This really fine, thought-provoking disc celebrates a composer whose career looks ad hoc but who strived against many odds to assert her musical values.

Jonathan Woolf

Buying this recording via a link below generates revenue for MWI, which helps the site remain free