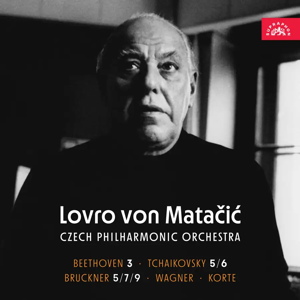

Lovro von Matačić (conductor)

Czech Philharmonic Orchestra/Lovro von Matačić

rec. 1959-1980, Dvořák Hall, Rudolfinum, Prague, Czechia

Supraphon SU4354-2 [6 CDs: 379]

I am immediately struck by the lightness, clarity and precision of the Czech Philharmonic under Lovro von Matačić here; these qualities, in combination with the excellence and transparency of the recorded sound could easily convince you that you were listening to a much more modern recording. I note that all six discs are AAD but no one will find anything to complain about; their analogue origin is not an issue. Furthermore, being habituated to the richer, denser sound of the BPO under Karajan or even Cluytens in this era, I was surprised by the degree to which von Matačić’s way with the Eroica shows that “period” sensibility is not an invention of the 80s. That impression is further enhanced by the grainy timbre of the Czech woodwind and the fact that, in the words of a contemporary critic quoted in the notes, von Matačić’s “Beethoven is austere, strict, yet truly classical and grand.” Everything he conducts has a great energy and impulse without ever becoming blowsy.

The change from Beethoven to Wagner is startling; we move from the dawn of Romanticism to its apogee, from classically spare to its lush efflorescence. It is as if we are hearing a different conductor-orchestra pairing. The playing is so highly charged that even a voice-maven like me hardly misses the singers in this arrangement of music from Götterdämmerung into a powerful twenty-five minute suite.

The first of the two Tchaikovsky symphonies here, No. 5, grips the listener from its first notes, not least because of the beauty of tone von Matačić secures from the Czech orchestra and his ability to establish and maintain tension as the music moves through the various themes. Despite their embrace of a highly Romantic affect, the orchestra’s homogeneity is again very much a feature of their playing. In the emotionally intense Andante cantabile, solo bassoon, horn and oboe are all first rate and the sweetness of the concerted string playing is beguiling, while that quintessentially Czech woodwind tone provides piquancy. Von Matačić certainly knows how to build to climax and make the music “swoon”, too. The sequence of waltzes in the Scherzo , from the stuttering hemiola of the first through to the sparkling Trio and concluding waltz, again employing hemiola, is elegantly despatched. It is amusing to read of the bewilderment and consternation the fury of the final aroused in contemporary critics. To be fair, even the composer was convinced of its bombastic failure but to most modern ears it is just the most glorious riot of passionate resistance. Von Matačić does not go overboard too soon but carefully controls the gradual ratcheting up of tempo and dynamics while building to the controversial peroration.

The Sixth Symphony must stand comparison with some formidable rivals. For me, no interpreter has ever bested Karajan’s 1971 recording on EMI and for a more recent account, I commend Currentzis’ wholly absorbing and eccentric version (review). In truth, I find von Matačić to be a little too swift, perky and angular in the introduction and Czech strings sound thin and undernourished in the yearning andante which ensues – but perhaps I am too habituated to the lush Berlin sound. The crashing start to the development, however, is splendid and again the conductor is pushing his orchestra with a very demanding tempo. Everything is right from then on, through to the stoic pizzicato conclusion. The “wooden-legged waltz” is again rather too fast for my taste; indeed, it lacks grace. The reprise at 4:33 unaccountably surges forward even more quickly and I don’t like it at all. That speediness is much better suited to the thistledown lightness of the third movement scherzo and its movement into martial frenzy. Von Matačić first brings a leaner manner to outlining the desperate main theme but there is no lack of Angst there and the spiralling into blackness is effective – if not as shattering as Karajan’s more laboured and painstaking descent.

Oldřich Korte’s The Story of the Flutes makes an odd pendant to the symphony, as it is mostly a noisy, bombastic, discordant piece interspersed with meandering flute duo noodlings; frankly, it does absolutely nothing at all for me. You can check out this same performance on YouTube should you so desire.

Half of the selection here is devoted to three Bruckner symphonies, beginning with one of the most challenging to bring off: the Fifth. Von Matačić’s introduction is exceptionally serious and deliberate, then unusually fast in the abrupt tempo change two minutes in, belying early impressions that this is going to be another grand, steady account. Both of the last two movements reverse that assumption; the Scherzo is decidedly urgent – indeed, the outer Ländler sections tend to sound more rushed than urgent and comparison with other versions indicates that it is one of the swiftest. For me, this nervous pecking at the staccati robs the movement of its inexorable sense of forward motion.

The opening of the finale promises better; more than any conductor I know, von Matačić emphasises the gawky humour of the clarinet’s interjections before a really weighty treatment of the fugal theme, but again, this emerges as one of the fastest renderings on record, comparable with Roegner, but for me Roegner finds greater overall consistency and coherence compared with Von Matačić’s more “stop-go” approach. Again, there is an odd sense of him pecking at the rhythm of the second fugue and it sounds fragmentary, failing to cohere. I miss the massive dignity of more “monumental” interpretations and it is not a Fifth I feel inclined to return to. The conclusion is loud and brash but not convincing; there is more than an element of “sound and fury signifying nothing”. This performance simply doesn’t gel and I can only conclude that von Matačić initially decided on a strategy which – at least for this listener – backfires.

For the Seventh, von Matačić sounds like a different Bruckner conductor. Thankfully, he drops notions of barrelling through the music and eschews any capricious alternating between extremes of tempo; his timings are now in line with those of my favourite recordings by such as Eichhorn and Haitink with the VPO in 2019; the music sings and surges without any unduly agogic instances and the CPO sounds wonderful, recorded in the rich, blooming acoustic of the Rudolfinum. Everything proceeds as it should and the coda is absolutely magnificent – especially the horns; galaxies wheel and collide! The Adagio is similarly wholly successful and here von Matačić’s application of rubato in the Gesangsperiode is apt and subtle, abetted by beautiful string tone. The first climax at 10:46 is superb and the second at 19:08 completely satisfying; again, I note the lovely brass playing which ensues – especially the trombones and Wagner tubas which provide a magically atmospheric conclusion the movement. The Scherzo is taken quite steadily and is heavy with menace, the Trio unusually lazy and languorous but lyrically sustained. The pace of the finale is likewise very measured but builds assuredly and yet again the brass are “awesome”; one could complain that the last two minutes are a bit jumpy as von Matačić somewhat over-tinkers with the tempi, pulling them around too much but the results are undeniably exciting. In my judgement, von Matačić’s Seventh is as rewarding as his Fifth is problematic

That leaves the Ninth Symphony – three movements only, of course. It begins imposingly – those Czech horns again; the tempo, phrasing and dynamics are right and the first grandiose outburst at 2:26 really makes its mark. The cantabile passage flows mellifluously but as in the two previous Bruckner symphonies, I am occasionally conscious of von Matačić pulling back rather too obviously and some coughing obtrudes, although we are not told that any of these performances was live. In compensation, the sheer sound of the CPO is ever a joy. This is a reading on the swift side but I have no problem with that emphasis upon the dramatic over the reflective and the coda is gripping. The Scherzo is fine, but I have heard more bite and attack in the pounding ¾ rhythm and it is taken a fraction too fast for me. The Trio is fleet and liquid but it is all a little lacking in the balefulness a steadier beat imparts. For some reason, the opening of the Adagio sounds a little thin of tone compared with my favourite versions and the sublimely beautiful and ambivalent second theme is actually taken too slowly – in direct opposition to von Matačić’s habitual tendency toward faster speeds. I do not find here the magical sense of concentration; it actually drags somewhat and the great “sunburst” moment at 16:32 is most disappointing: thin and under-powered.

In the end, a fine but not exceptional Seventh notwithstanding, I find myself wondering why Supraphon opted to include so much of von Matačić’s Bruckner in this tribute, when he excelled in so many other areas. Perhaps that is what they had in their archives, but more of his Beethoven rather than Bruckner’s Fourth and Ninth symphonies would have been welcome as I do not think Bruckner was his forte.

Ralph Moore

Buying this recording via a link below generates revenue for MWI, which helps the site remain free.

Contents

Beethoven: Symphony No. 3 in E flat major, Op. 55 ‘Eroica’ rec. 15-18 March 1959

Wagner: Götterdämmerung. Orchestral Suite from Opera rec. 24 March 1967

Tchaikovsky: Symphony No. 5 in E minor, Op. 64 rec. 20-22 March 1960

Tchaikovsky: Symphony No. 6 in B minor, Op. 74 ‘Pathétique’ rec. 10-14 February 1968

Bruckner: Symphony No. 5 in B flat major rec. 2-6 November 1970

Bruckner: Symphony No. 7 in E Major rec. 20-23 March 1967

Bruckner: Symphony No. 9 in D Minor rec. 4 & 5 December 1980