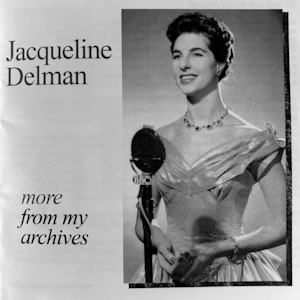

Jacqueline Delman (soprano)

More from my archives

Private recordings from radio and TV, mostly live

Oak Grove [2 CDs: 153]

Three years ago I received a 2 CD set with private recordings from Jacqueline Delman’s archives of reel-to-reel tapes (review). I was enthusiastic about them and nurtured a secret dream that one day there might arrive a sequel – and lo and behold, a few weeks ago the postman delivered a neat little parcel. Here are my reactions.

As was the case with the first volume, the sound quality varies – no wonder, considering that the earliest recordings were made almost 70 years ago – but Christer Eklund, who has transferred and restored the originals, has worked wonders. Don’t expect hi-fi quality, but enjoy this invaluable documentation of a versatile singer. Born and educated in London she very early made her opera debut in Rome as Mimì in La bohème aged 21 but a few years later she went to Sweden, married, and signed a contract with the Royal Opera in Stockholm in 1960. Fluent in several languages she has a wide-ranging repertoire both in opera and concert, and this second volume encompasses both standard repertoire and rarities.

The opera and operetta section which opens the first CD is an interesting mix. Here, well-known arias from Carmen and Manon Lescaut – exquisitely sung with great care for nuances – rub shoulders with Lauretta’s charming aria from Le Docteur Miracle, composed by an 18-year-old Bizet, and Quitiera’s aria from Die Hochzeit des Camacho, composed by the even younger Felix Mendelssohn, only 16 at the time. Millöcker’s operetta Die Dubarry is not as universally known as Der Bettelstudent, but the aria “I give my heart” is certainly a melodic gem that should entice all operetta lovers, sung here with glitter in the voice and with the right sentimental twist, while “I adore you, my dear” from Offenbach’s masterly La Périchole is so seductive. Both these are conducted by the legendary Mantovani from TV-shows, and the latter number receives a long round of applause. The section is rounded off with Gianetta’s “Kind sir, you cannot have the heart” from Gilbert & Sullivan’s The Gondoliers, again so finely nuanced, which is Jacqueline Delman’s hallmark, whether in opera, operetta, or song.

The rest of this crammed issue covers her extensive song repertoire, apart from two brief baroque arias. The first, “Se tu m’ami”, is attributed to Pergolesi, but it is one of the Arie antiche which were collected and arranged by Alessandro Parisotti in the 19th century, and could just as well have been composed by Parisotti himself. No matter who is the originator, it is a charming little song, well worth its place in this collection. “Prophetic raptures” on the other hand is authentic Handel, although the oratorio Joseph and his Brethren is one of his least performed, due to its poor libretto. Another aria from that work was included in the previous volume, and this aria is a fine piece, which gives the singer ample opportunities to demonstrate her ability for florid singing. That talent is exposed to great effect in volume one in pieces like Adele’s Laughing Song from Die Fledermaus and Violetta’s great aria from La traviata.

French mélodies is a niche that suits Jacqueline Delman to perfection. That was very obvious in volume I, and her choices here only confirm that impression. Bizet, Debussy and Duparc appeared in the previous volume, and more Debussy is featured here. Ariettes oubliées are six delicious poems by Paul Verlaine, and Debussy’s settings are congenial. The fragrance of Verlaine’s words is lovingly transferred to music; my only regret is that I can’t pick the individual songs, since they are performed on one track; however, on second thought I realise that the six poems are so tightly knit together that they are a unit. The three remaining Debussy songs are also settings of the cream of French poets: Verlaine again, Baudelaire and Mallarmé. I have to admit that I have a special affinity for Ernest Chausson’s music. His Poème for violin and orchestra was an early find, and I regularly return to it, but his vocal writing also has an honoured place in my heart, and Chanson perpétuelle, whether in the original for full orchestra or, as here, for string quartet and piano, is a great favourite. The chamber variant is the more intimate and suits Jacqueline Delman’s sensitive reading.

German Lieder and Russian repertoire occupy the second disc. Of course Schubert, Mendelssohn, Wolf, and Richard Strauss are core repertoire for every Lieder recitalist, and here Jacqueline Delman has discriminatingly chosen fairly unhackneyed songs. Schubert’s Seligkeit is an old friend, but neither Das Echo nor the Suleika songs is on Schubert’s top-20-list. Any Schubert songs are welcome, and hopefully some listeners will find new favourites here. You can rest assured that her readings are well considered and sung all her customary capacity for nuances. This also goes for the two Mendelssohn songs – the cradle song Bei der Wiege sung with beautiful legato and And’res Maienlied, which depicts witches riding on broomsticks to the Brocken to encounter Beelsebub, with all the dramatic intensity one expects in this otherworldly milieu. She was introduced to Hugo Wolf’s subtle songs by her first voice teacher Mark Raphael, and as she writes in the liner notes, “it was natural for me to include songs by him in my first solo recording for Decca”. The two Mörike songs included here are glorious proofs of her insight. Finally, the three songs by Richard Strauss are further gems in this collection.

Her interest in the Russian repertoire has its roots in her early acquaintance with the legendary Russian born soprano Andrejewa von Skilondz, who from the mid-1910s was a leading singer at the Royal Opera in Stockholm, and after this career embarked on a career as voice teacher with famous international names like Elisabeth Söderström and Kim Borg among her pupils. She became Jacqueline Delman’s mentor and triggered her to sing Russian songs and also study the Russian language. It’s no exaggeration to say that there is a true authentic atmosphere about her singing of Tchaikovsky and Rachmaninov, the two most performed Russian composers. The typical melancholy of most of Tchaikovsky’s oeuvre is particularly well caught. Rachmaninov was generally more cosmopolitan in his tonal language, but there is often more than a hint of the gloom also inherent in Norwegian, Swedish and Finnish music. It is often said that the darkness of the long winters in the Nordic region is mirrored there. Glinka’s songs are less often heard outside the Slavonic world, which is a pity. Many years ago I heard the great Russian bass Evgeni Nesterenko in a recital, singing a handful of Glinka songs, and that was an ear-opener for me. He definitely didn’t sing Marguerite’s Song, which Jacqueline Delman does here, and it is a very fascinating Russian version of Goethe’s Gretchen am Spinnrade, immortalised by Schubert.

The very last song, Prokofiev’s The ugly duckling, is a true challenge for interpreter and audience alike. I wasn’t aware of Prokofiev’s song production until a few years ago when I had an all-Prokofiev disc with a selection of his not-so-numerous songs for review. He wrote some songs in his youth in the 1910s, but during his exile after the revolution he was largely inactive in this field until he returned to the Soviet Union in 1936, after which he mainly wrote songs based on Russian folk music. The ugly duckling, composed in 1914, has a text by Nina Alexeyevna, which of course is based on Andersen’s fairy tale. Stylistically it is bravely revolutionary expressionistic with harsh harmonies and bewildering accompaniment, that must have been a hard nut to crack for the audience at the premiere. At a playing time of around 13 minutes, it is more a dramatic scene than a song, and I believe that a present day audience could feel a bit disoriented. The formidable Russian mezzo-soprano Margarita Gritskova on the disc mentioned above made a great impact when I first heard the piece, but Jacqueline Delman’s reading is on the same level, and she brings the disc to a stirring grand finale. The majority of the songs are accompanied by Geoffrey Parsons, who for many years was her regular accompanist.

To sum up, this compilation, together with its predecessor, is a valuable documentation of the versatility of Jacqueline Delman, both musically, repertoire wise and linguistically.

Göran Forsling

Availability: Artist (by email)

Contents

CD 1 [75:32]

Opera/Operetta

Millöcker: I give my heart from Die Dubarry [2:47]

Bizet: Micaëla’s aria from Carmen [6:10]

Bizet: Lauretta’s aria from Le Docteur Micacle [4:23]

Mendelssohn: Quitiera’s aris from Die Hochzeit des Camacho [5:32]

Puccini: In quelle trine morbide from Manon Lescaut [2:43]

Offenbach: I adore you, my dear from La Périchole [1:56]

Gilbert & Sullivan: Kind sir, you cannot have the heart from The Gondoliers [3:32]

French melodies

Debussy: Ariettes oubliées [18:05]

Debussy: Le jet d’eau [6:35]

Debussy: Colloque sentimentale [4:13]

Debussy: Apparitions [3:58]

Chausson: Chanson perpétuelle [8:04]

Baroque repertoire

Pergolesi: Se tu m’ami [2:56]

Handel: Prophetic raptures from Joseph and his Brethren [3:38]

CD 2 [77:58]

German Lieder

Schubert

Seligkeit [2:03]

Suleika 1 [5:22]

Suleika 2 [4:27]

Das Echo [3:02]

Mendelssohn

Cradle song [3:49]

And’res Maienlied [2:20]

Wolf

Lebe wohl [2:58]

Auf einer Wanderung [3:38]

Richard Strauss

Befreit [5:35]

Die Nacht [2:58]

Schlechtes Wetter [2:32]

Russian repertoire

Glinka

Marguerite’s song [3:12]

Tchaikovsky

Tell me why [2:54]

Cradle song [3:48]

Not a word, beloved [3:13]

Whether day dawns [3:25]

Rachmaninov

Lilacs [1:42]

To the children [3:29]

April, a festive Spring day [2:07]

Prokofiev

The Ugly Duckling [13:35]

Other performers

Various orchestras conducted by Annunzio Mantovani, Carmen Dragon, Meredith Davies, Anthony Bernard, Vilhelm Tausky, Stanford Robinson and Jean Pougnet

Aeolian String Quartet

Piano accompaniment by Geoffrey Parsons, Viola Tunnard, Martin Isepp and Jan Eyron.