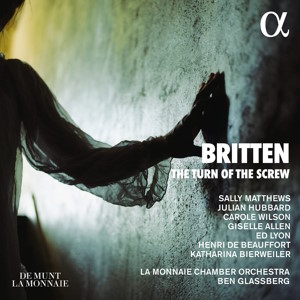

Benjamin Britten (1913-1976)

The turn of the screw (Opera in a Prologue and 2 Acts, Op. 54, 1954)

Governess – Sally Matthews (soprano)

Quint – Julian Hubbard (tenor)

Mrs Grose – Carole Wilson (soprano)

Miss Jessel – Giselle Allen (soprano)

Prologue – Ed Lyon (tenor)

Miles – Thomas Heinen (treble)

Flora – Katharina Bierweiler (soprano)

La Monnaie Chamber Orchestra/Ben Glassberg

rec. 2021, La Monnaie, Brussels, Belgium

Booklet includes English sung text and French translation, also notes in English, French and German

ALPHA 828 [2 CDs: 105]

Ed Lyon presents the Prologue possibly a little too declaimed yet with fair nuance. The Royal Theatre of La Monnaie is quite a resonant space for a chamber, yet sometimes set outdoor, opera and this affects the singing style. Lyon well contrasts forthright instructions and pondering the mysterious, underlying conditions and nature of responsibility. A moment of empathy for the child victims, ‘No time at all for the poor little things’ (tr. 1, 2:08) makes its mark. The solemn significance of the three-note piano motif (2:12), Benedict Kearns’ piano accompaniment ever reflective, is vivid, that motif expanding into the work’s main theme (tr. 2, 0:05).

The action of the opera is presented frenetically through a combination of Scenes and Variations. You can think of the latter like the Interludes in Peter Grimes which aren’t really that but orchestral commentaries on the immediate setting and its emotive impact. We first hear Sally Matthews’ Governess, the prime focus of the action, in Scene 1 (tr. 3) against a rugged, jolting carriage of tenor drum and timpani, nicely articulated by Luk Artois. Matthews brings a well-rounded portrayal of doubts in her new position and inherent love of children. But not having yet literally been spooked by the ghost Quint, is her climax, ‘A strange world’, top G sharp but only marked f (1:24), too distraught? Well, be warned, for Matthews’ portrayal distraught is second nature. From Ben Glassberg and La Monnaie Chamber Orchestra, Variation 1 (tr. 4) of the main theme has menacing density. For Scene 2’s first meeting with housekeeper Mrs Grose and the children (tr. 5), Matthews is accompanied by an ‘always expressivo’ violin solo, signalling a sensitive combination of anxiety and good intentions as she dwells expansively on the children’s charm, while Mrs Grose chatters about their goodness but also liveliness, the latter illustrated within the ensuing cacophony of four voices.

I compare this with the 2002 recording directed by Daniel Harding with the Mahler Chamber Orchestra (Erato 4563792 download only). In the Prologue Ian Bostridge is more animated than Lyon: he draws you in to the coming experience while his more marked softer passages have a conspiratorial quality. His pianist’s three-note motifs are a fascinating, lurking revelation. Harding’s carriage journey has a better-oiled crispness than Glassberg’s but is less vivid. Joan Rodgers’ Governess is a smiling, soft-hearted ingénue who can thus readily empathise with children. Her glossing over the climax ‘A strange world’ is more convincing in this context, but to realize much later that it’s she, not the children, who is innocent, is then more telling. The ensemble moving from two to four voices, more lightly articulated, is clearer, the Governess’ more petite, sweet violin a gentle wandering soul just like she seems.

Variation 2 (tr. 6) features the theme expanded on bassoon, harp and horn. In Scene 3 (tr. 7) Mrs Grose’s happiness at no longer having sole responsibility for the children, Miles and Flora, is quashed when the Governess receives a letter that Miles has been expelled from school for violence. Carole Wilson’s bluster as Mrs Grose, refusing to believe Miles violent, encourages Matthews to make the decision to do nothing which really pleases Wilson as both with a phrase, ‘It is all a wicked lie’ (2:12) which recalls Variation 2’s ruminations, opt blindly in favour of their idyllic environment. However, after Wilson’s ‘May I take the liberty?’ (2:49) to kiss her in congratulation, the diminuendo on these words should be clearer and the following silence filled with the sound of an actual kiss. In Harding’s account the diminuendo is clearer but there’s also no kiss.

Variation 3 (tr. 8) is an increasing display of natural beauty, with oboe, flute arabesques, then clarinet and bassoon involved. Glassberg makes this pastoral environment vividly present but not really soft, so more dissecting than calming. The softer Harding achieves more sense of repose, smoothness, beauty and delicacy in the flute’s high tessitura birdcalls. In Scene 4 (tr. 9) this is appreciated for Glassberg with comparable vigour by Matthews, ‘My darling children enchant me more and more’ (0:42) and you think, ‘Yes, literally.’ Her greater satisfaction is, with reference to her master, in doing ‘his bidding’ (1:56), brimming with sensuality. Matthews also makes telling her understanding of being ‘Alone’ with a top B flat (2:45), as she is throughout, like many of Britten’s protagonists, the outsider. For Harding, Joan Rodgers’ softer ‘Alone’ (the doubling oboe is marked ppp) is more pained, intimate and secretive. Unsurprisingly, when Quint appears on the tower, clarified for us for now and the future by the unworldly celeste (2:52), Matthews eagerly identifies him as her master, a wish-fulfilment quickly rationalized, then panic follows. Rodgers’ reaction is at first sweet and intimate, then guiltily rationalized and fearful.

Variation 4 (tr. 10), ‘very quick and heavy’, is a spooky prelude to the children’s ‘Tom, Tom, the Piper’s son’ opening Scene 5 (tr. 11). For Glassberg their singing is just vigorous, but the preceding variation has given it an edge. Again, when she’s alone, Quint appears to the Governess, this time in the window. Matthews, describing him to Wilson, moves from curiosity to horror. But the climax of the scene is the unexpected intensity of Wilson’s worst, hitherto buried, fears in a mantra, ‘Dear God, is there no end to his dreadful ways?’ (2:47). She quickly unpacks the horror, Quint being ‘free with eve’ry one’ but especially with Miles and Miss Jessel, the previous governess, then both Miss Jessel and Quint died. So, in this scene the principal ladies move from sharing contentment to sharing distress. Matthews is transformed to a firebrand protector of the children; Wilson admits she doesn’t understand but will support her. Most fully scored, the ‘brisk’ Variation 5 (tr. 12) conveys their evangelist energy. Harding’s children are more enthusiastic. Jane Henschel’s Mrs Grose is more secretive in her narrative, recalling it rekindling her fear, a better contrast with the later asseverations, particularly those of Rodgers. Harding’s Variation 5 is more purposive but misses the more attractive, ironic naivete of Glassberg’s.

In Scene 6, ‘The Lesson’ (tr. 13), Glassberg gives us supercharged children and piccolo, but when Matthews wants more from Miles she gets his most memorable song, ‘Malo I would rather be’ (1:29), a boy personally haunted, made further distinctive by obbligato cor anglais, sustained viola and harp backing all strikingly revealed, 14-year-old Thomas Heinen’s voice of pure innocence divulging loss of it. ‘Malo’ in Latin means both ‘I would rather be’ and evil, ‘malum’ means apple and evil, referenced in Miles’ second line, ‘Malo in an apple tree.’ So, Miles likes being tempted but is worried about becoming evil, which is the crisis of the opera. In Variation 6 (tr. 14) the song continues to haunt, notwithstanding the sprightliness of flute and clarinet. Harding’s lesson is delivered as more routine sportiveness by the children which makes the Malo song a stronger contrast. Julian Leang’s Miles is more searching, but also seems more knowing and guilty, while the linking with the cor anglais especially is more intimate, I felt like a snake coiling around him.

In Scene 7, ‘The Lake’ (tr. 15), the Governess, testing Flora on her knowledge of seas, finds she would name her country house lake the Dead Sea. For Glassberg, Giselle Allen as Flora shows entrancingly motherly affection in a lullaby for her doll (beginning at 1:28 with gorgeous flute and clarinet backing), combined later with a mature appreciation that everything changes. You first wonder ‘How can a girl be like this?’, then realize with your ghostbusting antennae, the former governess, Miss Jessel, has become part of Flora. As listener, you’re privileged to realize this before the new, present Governess. Cue Miss J’s appearance. The Governess sees the apparition (4:04), Matthews naming it with a screaming sforzando top A sharp (4:38) and now completely loses her innocence in realizing the children are lost. However, Variation 7’s horn solo of the main theme (tr. 16), gradually louder then soft again, against the celeste solos identifying phantom presence, shows the Governess’ determination to continue with her opposition. For Harding, Caroline Wise’s Flora is a smaller, more childlike voice and therefore apparently more innocent, creating a more ironic climax in Rodgers’ distressed realization Flora is aware of Miss Jessel’s presence. In Variation 7 Glassberg provides intense, dramatic impact, yet Harding is more graphically suggestive with a quieter celeste entry then built up with more sense of inevitability about the horn solo’s statement.

The celeste remains for Scene 8’s ‘At Night’ (tr. 17), with gentle semiquaver-filled melismas. But when these are extended by Quint, unseen, calling Miles, from Glassberg’s Julian Hubbard they become agonized in urgency to maintain companionship. In full view and sound Heinen’s Miles announces he’s here and Quint parades a catalogue of energetic activities as temptation. Enjoy the falling, yawning glissandos of Heinen trying to stay awake and the deftly rising ones of Hubbard’s ‘The long sighing flight’ (4:03) of the ‘night-wing’d bird’ (4:09), Then it’s Miss Jessel’s summons and Flora’s response and the alternation of ghost/child pairs. Miss J is less certain of her efficacy, but both children affirm their allegiance. Now enter the Governess to stop all this and Act 1 ends with Miles simply, poignantly stating a personal realization of loss of innocence, ‘You see, I am bad, aren’t I?’, a line Britten added to the libretto.

Harding’s Scene 8 begins with celeste softer and Quint’s call more distant to more spectral effect. Bostridge’s Quint’s melismas are more beautifully virtuosic and tempting, and the gallery of personas he can assume seems more attractive. Leang’s ‘I am bad’ is sung with regret more than Heinen’s plain, a touch bravura, statement of fact.

Act 2 begins with Variation 8 (CD2, tr. 1). In Glassberg’s handling, for me these orchestral passages convey the hothouse atmosphere more arrestingly than the voices. The clarinet further extends Quint’s melismas, a duet of anguished, yearning violins (the children) responds. An animated flute chirps, viola and cello mourn. A muted horn’s march seems dysfunctional; the sustained, expressive progress of bassoon and cello contains a dragging effort, the bassoon indicating Miss J’s appearances. Harding’s soloists are more poised and calculated, distilled and considered, less immediate than Glassberg’s.

Scene 1 (tr. 2) starts with a colloquy. Miss J blames Quint for her torment. Hubbard, fully in charge, explains it away, admits he seeks a friend but laughs off Allen’s offer, provoking a searing top C flat ‘Ah’ from her (1:10). From Hubbard, a catalogue of the qualities he requires from Miles as subservient mate so that, quoting Yeats, ‘The ceremony of innocence is drowned’ (1:57), the orchestral force making this seem like a black mass. Miss J wants the same, so in this the two can agree and ‘come together’ vocalizing the opera’s main theme in unison (2:27), Allen with a touch more force, even desperation, than Hubbard. In Harding’s colloquy Bostridge is more forward in focus so Vivian Tierney’s Miss J begins subservient, Bostridge, unlike Hubbard, not following the stage direction to laugh at Miss J, but their duet of shared goal is more suitably evenly balanced.

The scene then switches to soliloquy. The Governess (3:26) can’t find a saving course of action, Matthews’ agitation embodied by a ‘labyrinth’ of tremulous strings’ semiquavers, viola especially, yet she seems determined to fight on, another consistent characteristic of her character and performance. For Harding, Rodgers is skittering all at sea, as if swept around powerless by the strings. The bells which enter in the brief Variation 9 (tr. 3) suggest help may come but the chimes contain increasing discords of deviance: Glassberg makes more of these than Harding. In Scene 2 (tr. 4) Flora and Miles lead the worship, but the glissandi and hidden sexuality within the Latin text again suggest a black mass. With Glassberg, only the chipper Wilson is innocent. Harding’s children show more spirit and mischief in their singing, with Glassberg’s you feel simply a façade of propriety. The dense vocal texture of the quartet (3:24), the children’s ‘benedicite’ against Mrs Grose’s optimism and the Governess’ understanding the ghosts are ever with the children, might to advantage be clearer, albeit the resonant acoustic of La Monnaie is helpful in evoking a large spiritual space and the main message, Matthews’ top A shrieks of torment (3:51, 3:56), comes across. Heinen’s Miles is clear and polite in revealing he knows Matthews knows the truth and challenging her to act. She now feels she must escape. Variation 10 (tr. 5) has a maelstrom of woodwind to illustrate.

In Scene 3 (tr. 6) the Governess is distraught at finding Miss Jessel in the school room vowing revenge, Matthews ironically offering a tender, soft top G flat for ‘the very heart of my kingdom’ (1:20) she feels has been violated. Allen matches this with a screaming A flat will to be ‘closer’ (1:40). Matthews makes a rival claim for possession of the children, with a blood-curdling top C for ‘horrible, terrible woman’ (3:14), while her later A flats (3:47) certify she’ll ‘write’ to the Guardian. Matthews and Allen are evenly balanced while, for Harding, Rodgers dominates. Glassberg stunningly reveals the orchestration to be that of torment and nightmare for both parties. Alone, both Matthews and Rodgers are intensely distraught: Matthews more tearful in her passion, Rodgers still also warm towards the Master in her letter to him. In Variation 11 (tr. 7) the main theme very softly broods on bass clarinet stalked by alto flute, both then animated into a flurry of semiquavers by the rap of a glockenspiel. Glassberg compels your attention. You think, why two instruments? Because there are two ghosts.

This segues into Scene 4 (tr. 8). Miles, restless on the edge of his bed, is prompted by the cor anglais to sing his ‘Malo, Malo’ song. But the ghosts’ semiquavers remain and, because of the juxtaposition, you discover the kinship of outline between the song and main theme, both owned by the ghosts. When the Governess enters, she questions Miles, ‘Is there nothing you want to tell me?’. Quint, unseen, immediately calls ‘Miles’ who shrieks and lies that’s because he blew the candle out. In Variation 12 (tr. 9) Quint begins tempting Miles to take the letter written to the Guardian, Hubbard often going into parlando and finishing with a glissando at ‘easy to take’ (1:11), melodrama for us but scary for Miles. For Harding, Rodgers and Bostridge play Scene 4 more quietly and intimately, Rodgers more affectionate in questioning, Leang less awkward in response. As Scene 5 begins (tr. 10), Miles goes towards the letter, takes it and the cor anglais plays the ‘Malo’ song confirming its centrality in Miles’ guilt. Variation 13 (tr. 11) appears at first to be a calm interlude but, as with the bells earlier, discords increasingly creep in. For Glassberg, Kearns makes these clear, yet this contradicts Britten’s marking ‘Easy and graceful’ which Harding’s pianist creamily follows and, because the discords remain, creates a more unsettling effect than Kearns’ spotlighting.

Another segue, into Scene 6 (tr. 12) reveals this is Miles playing, over which Mrs Grose and the Governess salivate. Glassberg’s Kearns is suitably demonic in Miles’ first piece and nimbly fingered in the second which accompanies Flora playing cat’s cradle. As often, Glassberg’s emphasis is on stunning impact and propulsion, but here I prefer Harding letting us hear the voices more clearly and some softer and sweeter pianism. Wise’s Flora for Harding more beguilingly coaxes Mrs Grose asleep than Bierweiler’s for Glassberg (2:37) while Miles’ playing mesmerizes the Governess until she realizes Flora has disappeared. Variation 14, ‘Triumphant’ (tr. 13) is Kearns and Glassberg’s fittingly seized opportunity to present a nasty victory parade where Harding and pianist present a polite one.

In Scene 7 (tr. 14) Flora is found by the lake and the Governess knows Miss Jessel will also be there, but is invisible to Mrs Grose while Miss J and Flora conspire to refute the Governess’ sighting, compellingly with Flora’s song, for Glassberg Bierweieler with spiteful relish enhanced by manic piccolo (1:41), culminating in a scream of hatred (2:06). Matthews is left alone in a searing passage of self-censure, admitting her failure and ‘there is no innocence in me’. Harding’s orchestra is less forward and frenetic than Glassberg’s but this makes the text and ensemble clearer where four voices sometimes sing simultaneously and often overlap. Wise’s Flora is more playful, even her less penetrating scream. Rodgers’ isolation is more that of personal grief than Matthews’ epic declamation.

Variation 15 (tr. 15) is huge posturing in crescendos from ppp to fff and manic piccolo returning. Glassberg scares us where Harding, more detached, observes. In Scene 8 (tr. 16) Mrs Grose and Flora are flitting but the former has now experienced the horror of Flora’s dreams. This exonerating the Governess only makes her determined to face the crisis and try to save Miles on her own. The two meet alone, but then Quint calls to Miles, who will tell the Governess everything, but not yet. He confesses to taking the letter. It’s the Governess’ time to tempt and command, ‘Only say his name and he will go for ever’, at which Miles bursts out ‘Peter Quint, you devil!’ (6:56). The Governess congratulates herself, ‘Together we have destroy’d him.’ In effect an epilogue starts when Hubbard intently and sorrowfully bids Miles farewell with his final melismas (7:39), but the Governess now sees Miles has died. Matthews has a top A climax for the song Malo (9:08) with the flute sharing two screams an octave higher, a piercing acknowledgement of Miles’ guilt transferred to her, bewitching a grief-stricken, eternal, desolate grey postlude. And there, too, you have the difference between the two approaches: Glassberg provides a vivid and sustained concentration on an unfolding tragedy where Harding offers a more varied distillation of contrasted moods and happier moments, so Bostridge’s softer farewell is tender and Rodgers sorrowingly accepts and quietly reconciles the outcome in repose. Harding irradiates finesse, light and shade; Glassberg brings you Armageddon.

Michael Greenhalgh

Help us financially by purchasing from