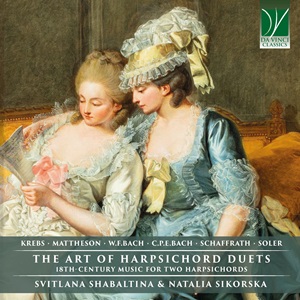

The Art of Harpsichord Duets

18th-century music for two harpsichords

Contents listed after review

Svitlana Shabaltina, Natalia Sikorska (harpsichords)

rec. 2012, St Lazarus Church, Lviv, Ukraine

Reviewed as a digital download with PDF booklet from Da Vinci Classics

Da Vinci Classics C00956 [69]

Keyboard instruments have played a major role in music history from the Middle Ages to the present day. They have come in various shapes: from large church organs for liturgical use to the very soft clavichord, to be played in the intimacy of a private room. They participated in ensembles, but were also used separately, and this has resulted in a large repertoire, varying from easy pieces for amateurs to virtuosic works for professionals. The disc under review is devoted to a special kind of keyboard repertoire: music for two keyboards. There is not that much repertoire of this kind, for a simple reason: keyboard music was usually written and printed for amateurs, and only a few of these could afford two keyboard instruments. This kind of music was also not of interest for professionals because public concerts were rare before the mid-18th-century. There was simply no demand for such music. Pieces for two keyboards were written for a specific reason, or, as in the case of Soler’s Concertos, for two specific persons: the composer and his employer.

In 1766 Soler was appointed music tutor to Crown Prince Don Gabriel de Borbón, who was very talented and collected numerous keyboard instruments. One of these was a rare vis-à-vis organ which was housed in the basilica of El Escorial. Obviously, one is inclined to think that these concertos were written for this instrument, especially as their title refers to the organ: Seis Conciertos de dos Organos Obligados. There is one problem: the compass of the organ was largely identical with what was common at the time, but Soler’s writing covers an exceptionally wide range. However, the fact that the collection is dedicated to the Infante indicates that these concertos were written for performances by him and his teacher. It seems more likely that they performed them on harpsichords. The range of these concertos, FF to G”’, points in that direction: Domenico Scarlatti wrote some sonatas which explore this range and that indicates that the court owned at least one keyboard with this compass. Svitlana Shabaltina and Natalia Sikorska end their recording with the Concerto No 6, which consists of two movements in different and contrasting sections. Although it is not sure that Soler has been formally a pupil of Scarlatti, the latter’s influence is very clear here.

The fact that the Infante was not only Soler’s employer, but also his pupil, points in the direction of another connection: that between teacher and pupil. Undoubtedly, music for two keyboards could also be written for pedagogical purposes. That is the case with the Sonata in G minor by Johann Mattheson. He is best-known for his theoretical writings, but he was also a highly respected composer. The sonata was originally followed by a suite with four movements in the then common order (allemande, courante, sarabande, gigue). The piece was dedicated to his pupil Cyrill Wich, son of the English ambassador to Hamburg. The pedagogical purpose explains why such pieces are usually technically demanding, and this sonata is no exception.

Playing music together is also a way of becoming a better musician. As Chiara Bertoglio, in her liner-notes, puts it: “[Playing] together is always a formidable school for young musicians, and it is particularly valuable when one’s teacher plays on the same kind of instrument. For a harpsichordist, playing with a professional violinist is certainly very profitable, but playing with another harpsichordist teaches volumes without uttering a single word.” But it is also entertaining. François Couperin wrote that he used to play some of his instrumental music on two harpsichords with members of his family. Chiara Bertoglio mentions the Bach household as the place where not only the sons, but also friends and pupils were welcome to play music. It is easy to imagine that, for instance, some of Bach’s concertos for two harpsichords may have been played there without string accompaniment. However, it seems unlikely that the pieces by the two eldest sons included here have anything to do with that. Wilhelm Friedemann composed his Concerto in F, as it was originally entitled, in Dresden between 1733 and 1746; in 1733 he took up the post of organist at the Sophienkirche. There he took part in the musical evenings of the Electress Maria Antonia Walpurgis of Saxony. It resulted in the composition of harpsichord concertos and music for harpsichord solo. It is quite possible that this piece was performed during such an event. It is in three movements, and includes elements of a sonata and of a concerto.

The oeuvre of Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach includes very few pieces for two keyboards; apart from a sonata, which is an arrangement of a trio for keyboard and transverse flute, there are the four ‘little duets’; they probably date from after 1768, when Bach was working in Hamburg, where he had succeeded Georg Philipp Telemann as Musikdirektor. It seems possible that these duets are also meant for performance by teacher and pupil. They are different in content and in length; the first two are the longest, the other two very short.

Johann Ludwig Krebs may have been one of those pupils who attended the Bach household and took part in performances. He was Bach’s favourite student, and some of his organ works are stylistically so close to Bach’s that they were attributed to the latter. In 1753, he performed at the court in Dresden, for which his Concerto in A minor was written. The first movement has the character of a solo concerto: the first harpsichord has the busiest part, and the second largely provides the accompaniment. In the second movement, the two keyboards are treated on a more equal footing. That is also the case in the last movement. The piece includes passages in which the two keyboards play in unison or in parallel motion.

Lastly, Christoph Schaffrath: he was one of a group of composers who played an important role in the musical life of Berlin, at and around the court of Frederick the Great. Not much is known about Schaffrath before the 1730s. In 1734, he entered the service of Frederick the Great, who was still Crown-Prince at that time. Frederick started his own chapel in Ruppin, which moved to Rheinsberg in 1736. With his accession to the throne in 1740 Schaffrath became harpsichordist in his chapel. But in 1741 he entered the service of Frederick’s sister, Anna Amalia. It seems this resulted in Schaffrath’s leaving the court, as his name does not appear in a list of musicians of the chapel from 1754. In his oeuvre we find quite a number of pieces with the title of duet, mostly for keyboard and a melody instrument, such as the oboe or the violin. It is very likely that the keyboard parts of these duets were to be played by Christoph Schaffrath himself and therefore reflect his own brilliance as a keyboard player. In the Duetto in C the second keyboard could have been written for Anna Amalia, who was a very good keyboard player herself. In this duet episodes for one of the keyboards alternate with passages in which the harpsichords join each other. But the duet never gets an ‘orchestral’ character, because when the harpsichords play together their bass parts are identical. This assures a great amount of transparency.

As I already noted, the repertoire for two keyboards is not that large. This explains why most of the pieces performed here are available in other recordings. That goes especially for the work by Wilhelm Friedemann Bach; in comparison, the pieces by his brother and those by Schaffrath and Mattheson are far less well-known. The two artists, both of Ukrainian birth, play two different instruments: copies after Hemsch and Ruckers respectively. They have divided the first and second parts among themselves. They are a perfect match and deliver energetic performances. I was a little surprised by the tempo of the first movement in Wilhelm Friedemann Bach, which I have heard played more speedily. However, the tempo indication says ‘allegro e moderato’, and therefore it makes much sense. This is a most enjoyable recording, and in the concerto by Soler the two artists let their hair down, and there is much Spanish flair and panache in their performances. It makes for a rousing conclusion to this entertaining programme.

N.B. The recording dates from 2012, but was released only in 2024.

Johan van Veen

http://www.musica-dei-donum.org

Availability: Da Vinci Publishing and Qobuz

Contents:

Johann Ludwig Krebs (1713-1780)

Concerto in A minor (Krebs-WV 840)

Johann Mattheson (1681-1764)

Sonata in G minor

Wilhelm Friedemann Bach (1710-1784)

Duetto (Concerto) in F (BR WFB A 12)

Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach (1714-1788)

Vier kleine Duette (Wq 115 / H 610-613)

Christoph Schaffrath (1709-1763)

Duetto I in C

Antonio Soler (1729-1783)

Concerto No 6 in D