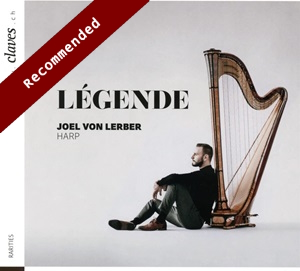

Légende

Joel von Lerber (harp)

rec. 2021, Berlin

Claves CD 50-3048 [61]

This CD has might be said to have a rather ‘brave’ programme, insofar as of the seven composers represented only two, Fauré and Liszt (the latter represented by an arrangement for harp), are likely to be familiar names beyond those with a particular fondness for the harp. To be more positive, perhaps the presence of those two names may tempt others to investigate the disc. I hope that that may be the case – and would guess that more than a few of those so-tempted might enjoy the disc.

Though several of the pieces recorded here were written in the twentieth century, the disc might reasonably be described as presenting music indebted to nineteenth-century romanticism. The title chosen for the disc (Légende) is apt. Specifically, it is borrowed from one of Henriette Renié’s compositions: Légende d’aprês “Les Elfes” de Lecomte de Lisle. Consideration of Leconte de Lisle’s poem makes clear what kinds of legends the album is dealing with. It is a narrative poem which begins with a scene of happy elves dancing in a forest clearing late at night. A knight on a black horse enters the clearing, his golden spurs shining in the darkness and moonlight lighting up his silver helmet. The elves surround him and their Queen asks him about the purpose of his journey and warns him that evil spirits live in the forest. She invites him to dance with her, but he refuses, explaining that he is on his way to meet his bride-to-be and that the two will be married on the next day. He spurs his horse and rides on into the forest, only to be confronted by a mysterious white form, its arms held out. The phantom declares itself to be the ghost of his beloved, already dead. Hearing this, he falls to the ground and dies. Clear analogues for the poem include Goethe’s Der Erlkonig and Keats’s La Belle Dame sans merci.

Renié’s Légende echoes the range of mood and emotion in Leconte de Lisle’s poem and there are some striking details. When we first ‘encounter’ the knight galloping on his black horse it is through music played on the low strings, with the rhythm alla marcia; the death of the knight is ‘painted’ in fast arpeggios. Renié’s music captures the ominous atmosphere, the moment of the challenge by the initially mysterious white figure and the fatal climax; the music’s use both of sudden glissandi and delicately lyrical traceries of sound is every bit as moving as its source poem (I am tempted to say more moving, since its ‘language’ is less dated). Joel von Lerber’s certainty of technique and imaginative insight do full justice to this intriguing composition.

Sometimes cross-pollination between the arts, when a work in one artistic medium is ‘seeded’ by one in a different medium, can result in complex sequences of interlocking works. There is one such case among the pieces on this disc: Liszt’s Le Rossignol (first version 1842, second version 1853), heard here in an arrangement for harp by Henriette Renié. Liszt’s work for solo piano was, in fact, based on a song by the Russian composer Alexander Alabyev (1787-1851), composed in 1825/6, which is a setting of a poem by Anton Delvig (1798-1863). Glinka was one of several composers who produced piano variations on the song. The poem, in three stanzas, consists of the outpourings of a profoundly unhappy female speaker, addressed to the nightingale. Renié’s arrangement appears to be firmly based on her immediate source by Liszt, but inevitably carries with it some of the earlier life of the poem and its vocal setting. Certainly, her arrangement has an impressive gravity, a sense of the weight of emotion in Delvig’s words, as filtered down to her through the chain of transmission outlined above. Yet it also finds time to evoke the song of the bird, addressed as the “vociferous nightingale” in the original poem.

Henriette Renié was an important figure in the modern history of the harp. She was playing the piano before she was five, but chose to take up the harp around the age of 8 after hearing a performance by the great harpist-composer Adolphe Hasselmans. From 1885 she was a student at the Paris Conservatoire. During her years as a student, she was awarded premiers prix in Harp, Harmony and Composition. She gave her first solo recital in Paris, aged 15, when she was already teaching harp privately. In later years, her pupils included Marcel Grandjany and Susann McDonald. During the Second World War, she prepared her Méthode compléte de harpe, which was published in 1946 and remains popular and widely used. She suffered a good deal of ill-health, which often curtailed her activities as performer and composer.

Renié is represented by a third work on this disc – her Danse des lutins (Dance of the Goblins). If there is a specific non-musical source for this work, I am unaware of it. Though more than one fairy story included dancing goblins – she might also have been aware of Antonio Bazzini’s notoriously difficult violin piece, La Ronde des Lutins, composed in 1852. Perhaps, if she needed a musical stimulus she might more probably have found it, as suggested in the booklet notes by Imke Griebsch, in Liszt’s Gnomenreigen (Dance of the Gnomes), one of his Two Concert Études, S.145, composed early in the 1860s. Renié’s own decidedly mischievous Danse des lutins certainly makes considerable technical demands on the performer, requiring considerable agility of both hands and feet, and of coordination to manage several harmonic changes with the pedals in quick succession. Such demands are met by Joel von Lerber with appropriate panache, as he captures the piece’s mixture of the playful, the menacing and the picturesque.

Fauré’s ‘Une chatelaine en sa tour’ returns us briefly to what I have called cross-pollination in the arts. Its title comes from the first verse of a poem by Paul Verlaine:

Une Sainte en son auréole,

Une Châtelaine en sa tour,

Tout ce que contient la parole

Humaine de grâce et d’amour;

The lines have been translated thus by Richard Stokes:

A Saint in her halo,

A Châtelaine in her tower,

All that human words contain

Of grace and love;

The poem obviously meant a lot to Fauré – he wrote a vocal setting of it, which opens his cycle La bonne chanson, Op 61, published in 1894. The cycle uses nine texts chosen from Verlaine’s collection, also called La Bonne Chanson, which was published in 1870. Some 24 years later, Fauré returned to his setting of the poem and used part of it for this composition for harp alone.

Three of the remaining pieces in this entertaining programme draw on materials by a different composer: Wilhelm Posse‘s ‘Variationen über “Der Karneval von Venedig”’, Mikhail Mchedelov’s ‘Variationen über ein Thema von Paganini’ and Nicholas-Charles Bochsa’s ‘Rondeau sur le trio “Zitti zitti” du Barbier de Seville de Rossini’.

Wilhelm Posse was a German harpist and composer, born at Bromberg (in Prussia), His father was a military musician and Wilhelm’s future seems to have been shaped by that fact. His father gave him his early music lessons, but his son claimed to have taught himself to play the harp. If so, he did a remarkable job, since he gave a concert in Berlin when only eight years old. He went on to study (1864-72) at the city’s Neue Akademie für Tonkunst, before becoming, when twenty, solo harpist with the Berlin Royal Orchestra and the Berlin opera. He also taught harp, from 1890-1923, at the Berlin Hochschule für Musik. Much of his output as a composer consisted of arrangements for harp of works by Chopin, Liszt and others); he also wrote études for harp, such as his 8 Grosse Etüden fur Harf (c.1890) and various short pieces for the instrument. The theme used in the set of variations recorded here, ‘The Carnival of Venice’ was adapted by Paganini from an old Neapolitan song O Mamma, Mamma cara; he made it the subject of twenty sparkling variations and thus popularised the tune. I have described Paganini’s variations as sparkling; unfortunately, that is not an adjective I can apply to those by Wilhelm Posse, some of which are, indeed, rather lacklustre.

Fortunately, there is more colour and vivacity in Mikhail Mchedelov’s ‘Variationen über ein Thema von Paganini’. The theme is that of Paganini’s Capriccio No 24. Born in Georgia, this harpist, composer and teacher “studied music in Tibilisi and Moscow” before “he became a member of the USSR Symphony State Orchestra in 1933 and taught at the Moscow Conservatory and the Gnessin Academy of Music” (quotations from the booklet notes by Imke Griebsch). He wrote several treatises to assist those learning the harp and composed some short works for beginners and children. Griebsch writes that “His Variations on a Theme by Paganini is the best known of his compositions”. This is certainly true; indeed, I can only recall ever hearing one other piece by him called, if I remember correctly, ‘At A Festivity’. In his Variations on a Theme by Paganini he follows the form of Paganini’s work, by stating the theme, following it by 11 variations and closing with a freer ‘fantasy’. While hardly profound, this is a lively and engaging work, which makes use of many of the harp’s resources, and employs some subtle variations in tempo and dynamics.

The final work on this disc is the ‘Rondeau sur le trio “Zitti ziti” du Barbier de Séville de Rossini’ by Nicholas-Charles Bochsa. Bochsa was a talented harpist who wrote well for the instrument. However, alongside his musical career in Paris, he had a more disreputable career as a forger, fraudster, adulterer and bigamist. In his early career, before his criminal activities caught up with him, he wrote several operas for the Opéra-Comique. His compositions for the harp include several in which he ‘plunders’ (the term doesn’t seem inappropriate for Bochsa), although, in fairness, he does normally acknowledge his borrowings. I have in mind works such as his ‘Montechi and Capulette’, from Bellini; ‘Petite mosaique sur La Creation’ from Haydn and ‘dal tuo stellate soglio’ from Rossini’s Mosè in Egitto. Rossini was clearly a favourite of Bochsa’s and it is on that composer’s Barber of Seville that he draws in the work recorded here – specifically the terzetto from Act II. The result is a skilful and pleasant confection, written before the improvements to the harp made by manufacturers such as Erard and Pleyel. It would surely have been popular in more than a few Parisian salons and it gets a well-judged performance from Joel van Lerber, with some effective changes of emotional direction.

As a young man, the great English harpist and composer Elias Parish Alvars studied with Bochsa in London, to where Bochsa had fled from Paris after his criminal activities were discovered. Alvars went on to play across Europe, including periods as first harp at the Vienna Opera and as chamber musician to Frederick I of Austria. A website devoted to Alvars quotes some of Hector Berlioz’s (characteristically rapturous) praise of Alvars: “This man is a magician. In his hands the harp becomes a siren, with lovely neck inclined and wild hair flowing, stirred by his passionate embrace to utter the music of another world”. Written around the middle of the Nineteenth Century, La Mandoline responds to the contemporary popularity of that instrument. While La Mandoline cannot be said to be one of Alvars’ major works, it is undeniably attractive. It has remained a popular showpiece ever since its composition, as evidenced, for example, by the number of performances to be found on YouTube; this performance by Joel von Lerber is amongst the best I have heard.

In a programme full of works written in response to French poetry, Italian opera and the virtuoso extravagances of Paganini, Maurice Grandjany’s ‘The Colorado Trail, Fantaisie’ comes (both literally and metaphorically) as a breath of fresh air. Born in Paris, Grandjany started learning to play the harp when eight and was soon studying with Henriette Renié; at eleven he was admitted to the Paris Conservatoire, where he was taught by Alphonse Hasselmans. He gave his first solo recital when seventeen, made his London debut in 1922 and his first appearance in New York two years later. He moved to the USA in 1936, being appointed as Head of the Harp Department at the Juilliard School in 1938, where he taught until 1975. His students included several distinguished American harpists, such as Catherine Gotshoffer and Nancy Allen. Full of glissandi and harmonically complex colours, this Fantasie is a richly evocative celebration of the Colorado Trail (that at least, was probably what Grandjany had in mind; never having visited that part of the world, I found myself thinking of more modestly mountainous areas such as Snowdonia and the Pennines).

Throughout the disc the playing of the Swiss-born harpist Joel von Lerber is excellent; he draws out the character of each work (especially important in a programme made up of nine works, the longest of them under thirteen minutes long); his technique seems perfect, his touch sensitive and powerful as needed. The acoustic of Church Oberschönweide in Berlin is wholly sympathetic. All lovers of the harp will surely get much pleasure from this disc.

Glyn Pursglove

Help us financially by purchasing from

Contents

Gabriel Fauré (1845-1924)

Une chatelaine en sa tour, Op 110 (c.1918)

Marcel Grandjany (1891-1975)

The Colorado Trail, Fantaisie, Op 28 (1922)

Henriette Renié (1875-1956)

Danse des lutins (1911)

Wilhelm Posse (1852-1925)

Variationen über “Der Karneval von Venedig” (pub.1919)

Henriette Renié (1875-1956)

Légende d’aprês “Les Elfes” de Lecomte de Lisle (1901)

Elias Parish Alvars (1808-1848)

La Mandoline, Op 84 (c.1854)

Mikhail Mchedelov (1903-1974)

Variationen über ein Thema von Paganini (1962)

Franz Liszt (1811-1886)

Le Rossignol S250/1, (1842/1853). Arranged for harp by Henriette Renié.

Nicholas-Charles Bochsa (1789-1856)

Rondeau sur le trio “Zitti ziti” du Barbier de Seville de Rossini