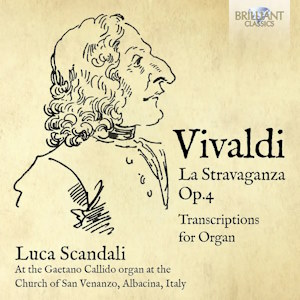

Antonio Vivaldi (1678-1741)

La Stravaganza Op. 4 (1716) – Transcriptions for Organ

Concerto in G (after Concerto in B flat, op. 4,1, RV 383a)

Concerto in F (after Concerto in G, op. 4,3, RV 301)

Concerto in A minor, op. 4,4 (RV 357)

Concerto in F (after Concerto in A, op. 4,5, RV 347)

Concerto in G minor, op. 4,6 (RV 316a)

Concerto in A minor (after Concerto in C minor, op. 4,10, RV 196)

Concerto in C (after Concerto in D, op. 4,11, RV 204)

Luca Scandali (organ)

rec. 2022, Chiesa San Venanzo Martire, Albacina (Alcona), Italy

Reviewed as a stereo 16/44 download

Brilliant Classics 96614 [65]

Italy has been the birthplace of many musical developments and genres. One of the latter was the solo concerto, which emerged around 1700 and in Vivaldi’s oeuvre received the form which was to become the standard for most of the 18th century.

In Germany, Johann Sebastian Bach can be considered one of the first who composed solo concertos in the Italian style. However, it was an aristocrat, Johann Ernst Prince of Saxe-Weimar, who was largely responsible for Bach’s becoming acquainted with the Italian concerto. He was the second son of Johann Ernst IX of the Ernestine branch of the Saxon house of Wettin. He was educated at the violin and received keyboard lessons from Johann Gottfried Walther. In February 1711 Johann Ernst left for the Netherlands to further his education. In Amsterdam he heard Jan Jacob de Graaf, organist of the Nieuwe Kerk, who used to play Italian solo concertos in his own adaptations for organ. This made such an impression on the young prince that he started to collect Italian concertos. Many of such works were published by Roger in Amsterdam. After his return to Weimar, Johann Ernst started to compose concertos in that style and asked his teacher Walther and Bach – who from 1708 to 1717 was court organist – to arrange them for organ or harpsichord.

Adaptations of music for different (combinations of) instruments were pretty common during the baroque period. Such adaptations could take different forms. Bach’s concertos for organ and harpsichord are often called ‘transcriptions’, but that does not do them full justice. Bach often made quite drastic changes, for instance by omitting certain passages or adding lines in order to make the counterpoint more complex. It is more appropriate to call them ‘arrangements’. It may be one of the reasons that especially the organ concertos are among his most popular works.

The present disc comprises seven concertos in keyboard transcriptions from a different source, known as Anne Dawson’s book. Nothing is known about this lady from the 18th century. This ‘book’ is an anthology of keyboard transcriptions, and may well be intended as a collection of exercises. According to Luca Scandali, in his liner-notes, it includes ten transcriptions of Vivaldi concertos: three from his Op. 3 and seven from his Op. 4. However, an edition of the concertos Op. 3 by Edmund Correia and Eleanor Selfridge-Field (1998-2005) comprises four concertos from the Op. 3. In his recording Scandali confines himself to the concertos from Op. 4, which were printed in Amsterdam in 1716. Apart from transcribing Vivaldi’s concertos, Anne Dawson added her own embellishments. As one can see in the tracklist, a number of concertos have been transposed to a different key. The liner-notes don’t indicate whether these transpositions are part of the book or the result of decisions by Scandali. The key of RV 316a is given as D minor, without an indication of transposition; the original key is G minor.

The frontispiece of this disc says that these are transcriptions for organ. That is not correct. Eleanor Selfridge-Field states: “The transcriptions of Vivaldi’s concertos found in the book compiled for Anne Dawson appear to have been written for a single-manual instrument (simultaneous duplication of tones between hands is carefully avoided).” She even thinks that they may have been inspired by the virginal, a keyboard instrument that was very popular in England until the late 17th century. That said, they may have been played on the spinet or on the harpsichord, the latter probably with a short octave. That does not exclude the possibility to play them on the organ. One should remember that in England organs with two manuals were rare. The organ that Scandali has chosen for this recording is also an instrument with one manual.

One may argue that an English instrument from the early 18th century would have been more suitable but I don’t know whether an appropriate instrument would be available. The organ played here is certainly a very nice instrument, which suits the character of Vivaldi’s music well. It was built in 1774 by Gaetano Callido, one of the main organ builders of the 18th century in Italy. The pitch is a’=435 Hz, the tuning ‘modified Tartini-Vallotti’. It is probably due to the tuning that the inventive harmonic progressions in Vivaldi’s concertos come off to full extent.

Scandali is an engaging performer, who obviously takes to this repertoire like a duck to water. Under his nimble fingers, Vivaldi’s concertos lose nothing of their brilliance and theatrical character. It is easy to understand why a composer like Bach and the unknown Anne Dawson felt attracted to them and wanted to study and to play them with their own means.

Those who love Bach’s concerto arrangements will certainly appreciate these more modest transcriptions, which have a value of their own. They are a nice complement to the better-known Bach works.

Johan van Veen

www.musica-dei-donum.org

twitter.com/johanvanveen

Help us financially by purchasing from