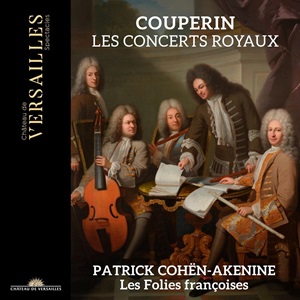

François Couperin (1668-1733)

Les Concerts Royaux

1er Concert in G

2e Concert in D

3e Concert in A

4e Concert in e minor

Les Folies Françoises/Patrick Cohën-Akenine

rec. 2021, Musée Instrumental, Provins, France

Reviewed as a stereo 24/96 download with pdf booklet from Outhere

Château de Versailles Spectacles CVS099 [61]

The name of François Couperin is inextricably linked with the harpsichord. Four books with harpsichord pieces were published between 1713 and 1730, and in 1716/17 he published his treatise L’Art de toucher le clavecin. He was also educated as a player of the keyboard and was for many years organist, first, from 1685, at St Gervais and then from 1693 onwards also at the court. He acted in this capacity for three months a year, alternating with three colleagues.

At about that time he started to compose chamber music, which shows the influence of the Italian style. As Italian music was not then appreciated in France, he didn’t present them under his own name. The sonatas from the 1690s were later included in the four sets of sonatas and suites printed in 1726 under the title of Les Nations. These can be counted among Couperin’s most famous instrumental works, together with the two Apothéoses. Before that, in 1722 and 1724 respectively, he had published four Concerts Royaux and ten pieces of the same kind under the title of Les Goûts-Réünis ou Nouveau Concerts.

The four Concerts Royaux are mostly recorded as a set. They were published as an appendix to the Troisième Livre de Clavecin on two staves, suggesting a performance on the harpsichord. However, in his preface Couperin explains that they can also be played on a variety of instruments, such as the violin, the flute, the oboe, the viola da gamba and the bassoon. This was certainly no novelty: before him, Charles (or François) Dieupart and Gaspard Le Roux had also suggested performances of harpsichord pieces with several instruments.

Couperin himself played his Concerts Royaux at the chamber concerts of Louis XIV with André Danican Philidor (oboe), François Duval (violin), Pierre Dubois (bassoon) and Hilaire (Alarius) Verloge (viola da gamba). It is often assumed that he composed them in 1714/15 – that is, at the very end of Louis XIV’s life (he died on 1 September 1715). But he merely writes that he “arranged them by key and preserved the titles under which they were known at court in 1714 and 1715”. From this statement, we have to conclude that those are the years he put them together in the form we know them. Individual pieces may be considerably older. There can be no doubt that they reflect the rather conservative taste of the Sun King. That doesn’t mean that they are devoid of Italian influences, but Couperin incorporated them in such a way that they fit into the traditional French style which dominates here.

The four concerts open with a prélude which is followed by a sequence of dances; some of these have the additional description of air. The 2e Concert closes with the only piece with a title, Échos, which has the form of a rondeau, which was frequently used. The 4e Concert closes with a forlane en rondeau. In this work, we find the only specific reference to the Italian style: a courante française is followed by a courante à l’italienne. The 3e Concert ends with a chaconne, a form which was especially popular in France and part of every 17th-century opera.

The title of the ten concerts published in 1724 reflects Couperin’s ideal, which he wanted to express in his instrumental works: the blending of the two main styles of the time, which for so long had been rivals. Thomas Leconte, in his liner-notes, explains that these ideals are realised in different ways in the four Concerts Royaux. The 2e Concert, for instance, is not unlike an Italian sonata in its sequence of slow, fast, slow, fast; the second and fourth movements are fugues, as in many sonatas by Corelli. The Echos then brings us back to France. Interestingly, the complete title (not given in the tracklist) is Échos tendres et champêtres – the latter term refers to the countryside. Many pieces by French composers of the 18th century include such references, as part of the Enlightenment was the admiration of the countryside, with its ‘natural’ living conditions. An instrument connected with the countryside was the musette, and pieces called after it also often appear in instrumental music, here in the 3e Concert. The mixture of the French and the Italian style in the 4e Concert has been mentioned already.

The alternative instrumentations Couperin himself mentions offer many different opportunities to performers. This means that despite the number of recordings, it is often possible to come up with a real alternative through the use of different instruments. The Trio Sonnerie (ASV Gaudeamus, 1986) recorded the Concert Royaux with violin and basso continuo, Musica ad Rhenum (Brilliant Classics, 2004) used transverse flute and violin. Even if ensembles use the full range of instruments, as is the case here, there are various opportunities to employ them. One can decide to allocate each movement to a different instrument or combination of instruments. Another possibility is to vary between one phrase and the next. Instruments can play on their own or in various combinations, playing colla parte. In the recording by Les Folies Françoises the instruments mostly participate in different combinations in the various movements. The 4e Concert is an interesting case, in that the French courante is for the most part played by winds, whereas the Italian courante is entirely performed by the violin – the instrument most strongly associated with the Italian style.

These pieces are available in a number of recordings, and as I indicated, one does not need to choose, as many of them offer different solutions with regard to the line-up. I am quite happy with this production; not only do we get here the full array of instruments mentioned by Couperin, but they are used in different ways, which results in colourful performances. The character of the individual pieces comes off perfectly. Elegance and refinement were highly appreciated at the time, and that is exactly what we get here.

If you don’t have these concerts in your collection yet, this disc may well the performance to go for – and if you already have a recording in your collection, this one is a worthy addition.

Johan van Veen

http://www.musica-dei-donum.org

Help us financially by purchasing from