Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky (1840-1893)

Symphony No 5 in E minor, Op 64 (1888)

Franz Liszt (1811-1886)

Mazeppa, Symphonic Poem No 6, S.100 (1851/54)

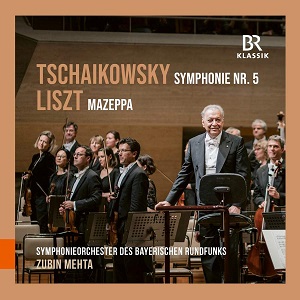

Symphonieorchester des Bayerischen Rundfunks/Zubin Mehta

rec. live, 25 February & 1 March 2013, Philharmonie im Gasteig, Munich

BR Klassik 900207 [60]

Selected from the Bayerischer Rundfunk archives, this is the first release from the Symphonieorchester des Bayerischen Rundfunks (BRSO) with its celebrated guest conductor Zubin Mehta, a recording made from concerts in the Philharmonie in 2013. The Indian-born maestro has strong connections to Munich. Having guest conducted both the BRSO and Münchner Philharmoniker, and having been the music director of the prestigious Bayerische Staatsoper from 1998 to 2006.

Around 1990 when the super-trio of Pavarotti, Domingo and Carreras with conductor Mehta were out promoting their ‘Three Tenors’ tour and bestselling album, I held the view that this enterprise was nothing but blatant commercialism and was devaluing opera, so for a time, I railed against them and their conductor, and boycotted their albums. This was all to change in the Berlin Musikfest 2015, when I reported on a concert in the Philharmonie, Berlin, when Mehta conducted the visiting Israel Philharmonic Orchestra in Schoenberg’s First Chamber Symphony for fifteen solo instruments followed by the greatest account I’ve ever heard of Mahler’s Ninth Symphony (review). My realisation that Mehta was a remarkable conductor of real substance, who had earned his renown, was instant, and soon reinforced by other recordings.

Liszt was a pioneer of the symphonic poem, a new type of programme music, writing a set of thirteen such works. I don’t see too many of Liszt’s symphonic poems in concert programmes; they seem to have fallen out of fashion. Lord Byron’s epic poem Mazeppa (1818) influenced Victor Hugo to write his own version of Mazeppa contained in his collection of poems Les Orientales (1828); Liszt, in turn, was inspired by it to write a solo piano work that became the fourth of his set of twelve Transcendental Études, S.139 published in 1852. In 1851, he reworked this fourth Étude into Mazeppa, his sixth symphonic poem, of which he conducted the premiere in Weimar in 1854.

According to legend, Cossack prince Ivan Mazeppa enraged a Polish nobleman by having an affair with his young wife. In retribution, Mazeppa was strapped naked to a wild horse, dragged through the steppes to Ukraine and eventually rescued by his countrymen. For the programmatical element of Hugo’s text, Liszt seems to divide his score into three sections: the wild ride; the collapse of the horse and Mazeppa’s brush with death; his liberation, renewal and transformation. Inherent in Liszt’s symphonic poem is the anguish, endurance and redemption afforded to the Romantic hero.

Mehta conducts an exhilarating account of Mazeppa. The level of perspicacity and virility that Mehta and the BRSO produce is striking; they revel in Liszt’s richly colourful score. The most enduringly admired recording of Mazeppa – and rightly so – is by Herbert von Karajan with the Berliner Philharmoniker in 1961 on Deutsche Grammophon, which has been reissued several times and remastered. Karajan’s evergreen account now has stiff competition from Mehta in Munich.

Tchaikovsky wrote the Fifth, one of his most admired symphonies, in the summer of 1888. It was a highly personal composition, as when he began work on the score he was suffering from depression and a lack of confidence, and was also physically unwell. Fortunately, he found some respite from his troubles in the countryside around his house in Frolovskoye, close to Klin outside Moscow. The E minor score reflects that emotional pain and anguish Tchaikovsky had been experiencing at the time of its composition. The Fifth can be seen as a journey from dark despair to bright optimism. In each movement, Tchaikovsky employs a recurring motto, sometimes named the ‘Fate’ theme.

Mehta is a trustworthy guide throughout Tchaikovsky’s impassioned journey, written while he was in a state of intense self-doubt; a convincingly sombre tone permeates the score, but out of the melancholy emerge beams of sunlight to provide a gratifying sense of positivity.

There is a high level of exuberance and buoyancy in the first movement; Mehta emphasises the wealth of themes and motifs; the playing of the pair of clarinets in the despondent ‘fate’ motto is especially successful. The main theme in the Andante cantabile, a movement redolent of a musical love-letter, stands out gloriously. The famous horn solo, one of the repertory’s greatest, is quite exquisitely played. Mehta demonstrates excellent control of the moods, contrasting the stirring drama contrasted with intense sorrow. As with the entire symphony, Mehta here adopts a sensible approach to tempo and dynamics without resorting to injudicious extremes.

Marked Valse. Allegro moderato, the third movement feels like welcome relief after all the emotional energy expended before. The performance of Mehta’s players in this light and lissom waltz has a persuasive charm. My watchwords in Tchaikovsky’s majestic final movement are anticipation and exhilaration, which Mehta and his players achieve adeptly, resulting in a stirringly dramatic conclusion.

Tchaikovsky’s Fifth Symphony has proved a highly popular choice for conductors in the recording studio and the competition amongst the many recordings is fierce. Of the older recordings, I savour Yevgeny Mravinsky conducting the Leningrad Philharmonic Orchestra in a red-blooded live account from 1960 at the Musikverein, Vienna, and remastered on Deutsche Grammophon ‘The Originals’.

Currently, I am greatly enjoying playing the first-rate account by Manfred Honeck with the Pittsburgh Symphony. I am not referring to Honeck’s admired 2006 recording with the same orchestra on Exton (review); my utmost praise goes to Honeck’s more recent live 2022 account recorded at Heinz Hall, Pittsburgh on Reference Recordings, part of the Pittsburgh Live! Series (review), where he conducts an even more successful performance which is hard to beat for its dramatic intensity. Mehta is thus up against more dynamic accounts of the Fifth, but none are able to match the level of profundity, coherence and sincerity that he and his players achieve in this outstanding live performance.

Both this and the Liszt work were recorded for radio broadcast by the Bavarian Radio and the sound quality is very satisfying; there is little unwanted noise and the applause at the conclusion of each work has been removed. The booklet contains a worthwhile essay providing basic information for each work.

Michael Cookson

Help us financially by purchasing from