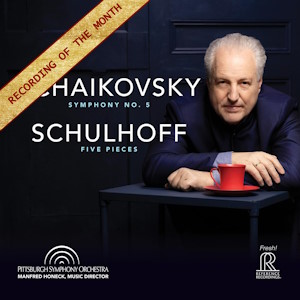

Piotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky (1840-1893)

Symphony No. 5 (1888)

Erwin Schulhoff (1894-1942)

Five Pieces for String Quartet (arr. Honeck/Ille) (1923)

Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra/Manfred Honeck

rec. live, 17-19 July 2022, Heinz Hall for the Performing Arts, Pittsburgh, USA

Reference Recordings FR-752 SACD [60]

This is the second time this partnership of conductor and orchestra has recorded Tchaikovsky’s Fifth Symphony; the first was also a live recording on the Exton label in 2006 which I haven’t heard (review); apparently it is very good but by all accounts this new release exceeds it in terms of both sound and performance. The excellence of this collaboration and the engineering of their recordings by Soundmirror in Boston is something we are beginning to count upon; the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra is now surely one of the very best in the world and several of their recordings over the last decade or so – especially their Brahms Fourth Symphony, the Strauss orchestral suites and their Eroica – have leapt to the head of my preferred lists.

There are so many recordings of Tchaikovsky’s Fifth Symphony that acquaintance with them all is impossible and choosing a favourite is almost aleatory; my own happens to be that by Frank Shipway with the RPO, which, I think, imparts something vivid and personal to the score, but Karajan and Mravinsky were always superb in Tchaikovsky and they, too, put their mark on the music – although of course they could not enjoy the high-tech sound of this Reference recording, even if Shipway’s “Audiophile Collection” digital account is very fine. Shipway and Karajan come in at a minute or two under fifty, while Mravinsky is more volatile and impetuous at forty-three minutes; Honeck’s forty-five minutes might represent the juste milieu, as his application of the “Andante” marking for the first two movements and “Allegro moderato” is more urgent, if not as headlong as Mravinsky’s, whereas there is generally more agreement about what pacing is apt for the finale. However, he does in a sense “take liberties” with the score – or some would say he simply does a conductor’s job and interprets it – as he explains in his notes: ““I have taken the liberty of creating a dynamic wave, first dropping the sound level and then immediately growing with a large crescendo to add dramatic emphasis as the music propels forward.” Again, in the second movement, he lengthens the caesura after the succession of massive chords eleven minutes in, and in the finale: “It is almost as if fate is continuously in conflict with the euphoria. In an effort to emphasize this contrast, I have asked for a subtle stretching of the semitone step”.

The first thing to strike the listener is the width of the dynamic range; no compression here. Honeck in his notes makes much of Tchaikovsky’s markings from ppp to fff; particularly helpful is the combination of bar numbers (for those with scores) and timings (for the casual listener) marking where Honeck wishes to emphasise a particular point. Of course, there is no need to follow his guide but the overall impression is one of a meticulously prepared and thought-out performance which coheres into a masterful organic whole. Especially graceful and convincing is Honeck’s command of phrasing; nothing sounds forced or self-conscious but the psychodrama of Tchaikovsky’s writing is vividly realised. The listener might already feel emotionally drained at the end of the first movement, yet there is still so much more to come.

In the second movement Honeck strikes the perfect balance between the lyrical and the tragic; the serenity of the beautiful melody is shattered by those fateful, chordal blows and the ensuing, elongated silence. The hemiolas of the third movement are subtly inflected without overt point-making. The fourth movement is a kaleidoscope of moods and effects; especially striking is the energy of the Allegro vivace (alla breve) section beginning at 3:11; Honeck works hard to ensure that all sections of the orchestra are felicitously balanced and succeeds magnificently in delineating the knife-edge tension between triumph and disaster which characterises this movement.

The Schulhoff dances are strange, exotic pieces, marked by a rhythmic adventurousness reminiscent of Holst and a perverse playfulness which to my ears is ironic and even parodic in mood, insofar as, for example, there is nothing of the serenade about the second “Alla serenata” and the Czech polka is distinctly satirical. I like the sensuousness of the fourth tango, which showcases the virtuosity of individual soloists, and the final tarantella is enormously energised. They might be designated as dances but little about them is joyful and they make fascinating pairing, being, like Tchaikovsky’s symphony, exercises in ambiguity.

Additional contextual and circumstantial interest is contributed by the sad fact that the composer , who was both Jewish and a Soviet citizen, was transported to Wülzburg, a Bavarian concentration camp where he died of tuberculosis aged 48 in 1942.

There is absolutely no evidence of this being a live performance beyond the crackling atmosphere of the occasion.

Ralph Moore

Help us financially by purchasing from