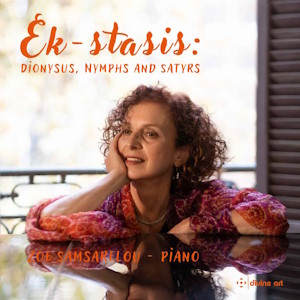

Ek-Stasis: Dionysus, Nymphs and Satyrs

Zoe Samsarelou (piano)

rec. 2022, Alternative Stage, Greek National Opera, Athens, Greece

Divine Art DDX21237 [2 CDs: 143]

The set aims to capture the essence, nature and exploits of the Greek god Dionysus and his crew. The album is sectioned into themes associated with the divinity: seduction, pathos, illusion, metamorphosis, transcendence, instinct, catharsis, mythos, paradox and transition. The label’s Web site says: “This creates an immersive experience that guides the listener through the various stages of the myth and offers a musical perspective on the story.”

Zoe Samsarelou is a Greek pianist who holds the post of Professor at the State Conservatory of Thessaloniki. She is the Artistic Director of the International Pelion Festival held yearly in Greece. She first majored in archaeology, and then pursued a career as a pianist. Mythology, history and the Arts have held a life-long fascination for her.

Dionysus was the god of agriculture and more importantly, wine. He also had a great interest in fertility, drama and festivities. His father was Zeus himself, and his mother was the mortal Theban princess Semele. In Roman mythology, he was known as Bacchus, hence the concept of Bacchanalian parties, which tended to descend into orgies. Admirers of Titian’s painting Bacchus and Ariadne (it now hangs in the National Gallery in London) will recall that he was accompanied by satyrs, maenads and the old man Silenus, who was nearly always under the influence of the vino. On a more serious note, Dionysus has been worshipped from the seventh century BCE even unto our own days. Most famous in recent years were the devotees of the Hellfire Clubs which thrived in the eighteenth century. He is associated with the Eleusinian Mysteries, Orphism and – in comparative religion – Jesus Christ.

As noted, Zoe Samsarelou has themed her recital. The music also falls into three main historical groups. The Baroque includes Rameau, Dandrieu, Couperin and Daquin. Then there are the romantics and moderns, among them Debussy, Dukas, Schmitt, Massenet and Bortkiewicz, plus the British composer Harry Farjeon. Next, several Greek composers, including the well-known Nikos Skalkottas. Lastly, Paul Juón, of Russian birth and Swiss and German descent.

Highlights for me include all the baroque works. Who can resist the vivacity of Jean Philippe Rameau’s take on the Les cyclopes or François Couperin’s thoughts on the Tendresses bachiques and the Fureurs bachiques? French Impressionism is represented with a transcription of Claude Debussy’s Prélude à l’ après-midi d’ un faune and two of his underplayed Six epigraphies antiques (Pour invoquer Pan, dieu du vent d’été, and Pour la danseuse aux crotales). Equally delicious is Déodat de Séverac’sLes Naïades et le Faune Indiscret, my favourite number in this recital.

Paul Dukas’s La plainte, au loin, du faune (from the 1920 collective work Le Tombeau de Claude Debussy) is hard-edged and a million miles away from his ubiquitous L’Apprenti sorcier. Lugubrious is a good description of Florent Schmitt’s Et Pan, au fond des bles lunaires, s’accouda from Mirages (also included in Le Tombeau de Claude Debussy).

A surprise for me was Sergei Bortkiewicz’s Valse grotesque (Satyre) from Trois morceaux, where hints of jazz and Gershwin abound. One of my favourites here is Ukrainian composer and pianist Mischa Levitzki’s dreamily romantic The Enchanted Nymph.

Then there is Harry Farjeon, the Englishman abroad. We hear his attractive, if Georgian, Pictures from Greece, which examine the Dryads, the Muses and the Graces amongst others.

Paul Juón, nicknamed the “Russian Brahms”, does not rely too heavily on the Brahmsian association in the nine pieces from his suite Satyre und Nymphen. Diverse movements present “scenes in life and times” of the characters. I especially warmed to the Valse lente: Dryaden reigen im Mondschein (The Dryads Dance in the Moonlight), and to the concluding Scherzo: Nymphe fiehl! Schnell! Satyr hascht dich (it can be creatively and playfully translated as “You’ve been caught, lassie!”).

The Greek composers’ works are a mixed bunch. Dimitri Terzakis’s Satyr und Naïaden features disjointed figurations, as he depicts the Satyr’s attempts to seduce the Naïades, with singular failure on their behalf. It is as dry as dust. His Ein Satyrspiel has more vivacity. From Tethys to the Mediterranean is part of Giorgos Koumendakis’s suite Mediterranean Desert. It is a dark and cheerless piece, with no relief, no Aegean warmth. Lina Tonia’s neo-impressionistic Prelude of a lost dream “is based on constant alternations between fast movements and small melodic patterns, like a floating between two different worlds, the world of dreams and that of reality”.

Two pieces by Nikos Skalkottas are included. He was influenced by the Second Viennese School’s serialism, traditional Greek music and the broader classical tradition. Echo, largely tonal, portrays the well-known myth of Echo and Narcissus. It is quite lovely, romantic and impressionistic, especially the aquatic effects. It ends quietly as befits the tale. Procession to Acheron is very different in mood. It depicts the flow of the river from the land of the living to Hades, and it is dark-hued and bitter.

Nestor Taylor’s Erinyes from Huit clos is a short but immensely powerful toccata. It depicts the Furies, “the goddesses of vengeance and retribution, who also oversaw the implementation of the punishment imposed on the people by the judges of Hades”.

Dionysus and the pirates, the voyage from Ikaria to Naxos by Dimitris Marangopoulos supposedly tells the story of when “the god Dionysus, disguised as a rich, young man, was seized by pirates to be held for ransom, and the miracles that happened”. Aspasia Nasopoulou’s Krokeatis Lithos-Lakonia from Raw Rocks (not Row Rocks as in the liner notes) is loud, slow and pesante. It is not something I would have chosen to conclude this long recital with. The background to the piece would seem to be more about geology than mythology.

The documentation leaves much to be desired. Most serious is the absence of analytical or descriptive notes about the many non-Greek numbers. Equally remiss is the lack of dates for these works. I was able to look them up, so presumably the producer of the disc could have done so too. The track listing gives one correct and then one incorrect set of dates for Jean-François Dandrieu, and has his name as “François”. Déodat de Séverac’sdates are also wrong. I think those given are of Gilbert Alexandre de Séverac, a French 19th-century artist.

At least, all the Hellenic pieces have concise programme notes. That is helpful, because the composers may not be widely known. (Flaws aside, I have borrowed several apt quotations from the booklet, with thanks.)

This fascinating recital explores a wide range of music set against the background of Classical mythology. Zoe Samsarelou plays enthusiastically, and reveals considerable depth of interpretation and technical expertise. The recording is clear and bright.

Divine Art’s Web site sums up this release’s unique programme: “It’s a celebration of the Greek spirit that has influenced humanity for over 2,500 years, highlighting the creativity and ingenuity of these wonderful composers.” It is a recital to savour slowly.

John France

To gain a 10% discount, use the link below & the code musicweb10

Contents

CD1

Jean-François Dandrieu (c.1682-1738)

2ème Livre, 6ème Suite, La sirène (1728)

Déodat de Séverac (1872-1921)

Les Naïades et le Faune Indiscret (1908-1919? publ.1952)

Dimitri Terzakis (b. 1938)

Satyr und Naïaden (2005)

Jean-François Dandrieu

2ème Livre, 6ème Suite, La bacante (1728)

Paul Dukas (1865-1935)

La plainte, au loin, du faune (Le Tombeau de Claude Debussy) (1920)

Giorgos Koumendakis (b. 1959)

From Tethys to the Mediterranean (from the suite Mediterranean Desert (1999)

François Couperin (1668-1733)

Pièces de Clavecin, 23ème Ordre, Les Satyres (1730)

Claude Debussy (1862-1918)

Prélude à l’après-midi d’un faune (arr. Leonard Borwick) (1894, arr. 1912)

Lina Tonia (b. 1985)

Prelude of a lost dream (2020)

François Couperin

Pièces de Clavecin, 4ème Ordre – Les Bacchanales – No. 1 Enjouements bachiques (1713)

Mischa Levitzki (1898-1941)

The Enchanted Nymph (1928)

Nikos Skalkottas (1904-1949)

Echo, AK77 (1946)

François Couperin

Pièces de Clavecin, 4ème Ordre – Les Bacchanales – No. 2 Tendresses bachiques (1713)

Pièces de Clavecin, 4ème Ordre – Les Bacchanales – No. 3 Fureurs bachiques (1713)

Florent Schmitt (1870-1958)

Mirages, op. 70, No.1 Et Pan, au fond des blés lunaires, s’accouda (1920-1921)

Nestor Taylor (b. 1963)

Erinyes (from Huit Clos) (2017)

Nikos Skalkottas

Procession to Acheron, AK79c (c.1948)

CD2

Jean Philippe Rameau (1683-1764)

Pièces de clavecin, 3ème Suite in D major: No. 8, Les cyclopes (1724)

Jules Massenet (1842-1912)

Bacchus – Le bapteme par le vin (arr. Alice Pelliot) (1908)

Sergei Bortkiewicz (1877-1952)

Trois morceaux, op. 24, no. 2. Valse grotesque (Satyre) (1922)

Dimitri Terzakis

Ein Satyrspiel (2003)

Louis-Claude Daquin (1694-1772)

1ère Suite, No.7 La ronde bachique (1735)

Claude Debussy

Six épigraphies antiques, No. 1 Pour invoquer Pan, dieu du vent d’été; No.4 Pour la danseuse aux crotales (1914)

Dimitris Marangopoulos (b. 1949)

Dionysus and the pirates, the voyage from Ikaria to Naxos (1998)

Harry Farjeon (1878-1948)

Pictures from Greece, op.13, (1906)

Paul Juón (1872-1940)

Satyre und Nymphen: 9 Miniaturen für klavier, op. 18 (?)

Aspasia Nasopoulou (b. 1972)

Krokeatis Lithos-Lakonia (from Raw Rocks) (2017)