Antonio Vivaldi (1678-1741)

Prelude in A minor (after the Concerto RV 355)

Jean-Marie Leclair (1697-1764)

Concerto in A minor, op. 7,5

Antonio Vivaldi

Concerto in B minor (RV 384)

Pietro Antonio Locatelli (1695-1764)

Concerto in E minor, op. 3,8

Jean-Marie Leclair

Concerto in D, op. 10,3

Antonio Vivaldi

Prelude in C (after Trio sonata RV 60)

Concerto in C ‘Per Anna Maria’ (RV 179a)

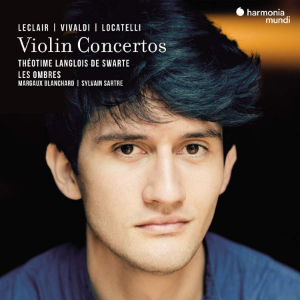

Théotime Langlois de Swarte (violin)

Les Ombres/Margaux Blanchard, Sylvain Sartre

rec. 2021, Large Hall of l’Arsenal, Metz, France

HARMONIA MUNDI HMM902649 [78]

When around 1600 a new style emerged in Italy, the violin emancipated from an ensemble instrument into a solo instrument that was given virtuosic and often idiomatic parts to play. In the course of the 17th century it became one of the main instruments, not only in Italy, but also above the Alps. The next stage was the birth of the solo concerto, in the last decades of the 17th century. In the 18th century many violin concertos were written, mostly by composers who were virtuosos on the instrument themselves. Antonio Vivaldi, Pietro Antonio Locatelli, Francesco Maria Veracini, Jean-Marie Leclair and Giuseppe Tartini were some of the great stars of their time, not unlike the violinists of the 19th and 20th centuries, who were celebrated in their time and are still held in high esteem. Three of these stars are represented on the present disc.

Antonio Vivaldi is the oldest of the three and one of the first who composed brilliant solo concertos for his own use. His father was also a skilled violist and Antonio received his first lessons from him. It was Francesco Lorenzo Somis in Turin, who further developed the young Vivaldi’s capabilities. Vivaldi composed most of his concertos for his own performances, but also for the girls of the Ospedale della Pietà, where he was appointed maestro di violino in 1703. One of these girls is known as Anna Maria; the Concerto in C which closes the programme, was written for her. The other concerto, in B minor, can be connected to Johann Georg Pisendel. In 1716/17 he stayed in Italy, where he met Albinoni and Vivaldi, from whom he wanted violin lessons, but who considered the German his equal. Pisendel developed into one of the main promoters of Vivaldi’s music above the Alps, and due to his collector’s mania, the library of the Dresden court chapel, of which he was concertmaster, includes the second-largest collection of pieces by Vivaldi in the world.

During one of his visits to Rome, Vivaldi met Locatelli, who was from Bergamo and was a pupil of Corelli. According to Olivier Fourés, in his liner-notes, there are good reasons to believe that the two became close friends. At the time Locatelli played in the orchestra of Cardinal Ottoboni. Between 1723 and 1727 he spent some time in Venice. He made several appearances in Germany, where he met Jean-Marie Leclair, and then settled in Amsterdam. Locatelli’s output is much smaller than Vivaldi’s, but his set of violin concertos Op. 3 has become groundbreaking, especially because of the inclusion of capriccios in each of the fast movements.

Jean-Marie Leclair started his career as a dancer, but later moved to the violin, and took lessons from Giovanni Battisti Somis, the son of the above-mentioned Francesco Lorenzo. Unlike in Italy and Germany, the violin played a modest role in France during the 17th century. It was used in the opera orchestra and for dance music, as well as in chamber music. Sonatas for violin and basso continuo were not written until around 1700. Among the first exponents of the violin as a solo instrument were Elisabeth Jacquet de La Guerre and Jean-Féry Rebel. In 1734 Jacques Aubert published his concertos Op. 17, the first of this kind in France. Three years later Leclair’s concertos Op. 7 came from the press, followed in 1745 by six further concertos as his Op. 10. It is in these concertos that the influence of the Italian style manifests itself. However, Leclair did not entirely embrace what was typical of the Italian style. In several prefaces he warned against exaggeration with regard to tempo and ornamentation. The two concertos included here are different from those by Vivaldi and Locatelli. The elegance that was a hallmark of the French style, is always present. That comes well off in these performances.

Locatelli, on the other hand, liked to show his technical prowess. The story goes that after performing a dazzling solo he exclaimed: “Ah! What do you have to say about that?” He must have been aware that only a few violinists of his time were able to perform the capriccios in his concertos. They are not obligatory, but performers of our time usually include them. A modern virtuoso as Théotime Langlois de Swarte has no problems with them. It is the challenge to a performer to give the impression that they are improvised on the spot, and that is where Langlois de Swarte succeeds with flying colours. One may think that these capriccios are nothing more than demonstrations of the player’s technical skills, but most of them have musical qualities as well, and that comes to the fore here too.

This recording is an impressive testimony of Langlois de Swarte’s technical skills, and there is nothing wrong with that. However, he does not forget to make music. This collection of virtuosic solo concertos is very enjoyable from a musical angle. This disc is an excellent demonstration of what was written for the violin in the high baroque era. They mark the gradual change from the soloist as primus inter pares to the status of a star, comparable with a singer in the opera. I should not forget to mention the ensemble which supports Langlois de Swarte, and is his perfect partner.

Johan van Veen

www.musica-dei-donum.org

twitter.com/johanvanveen

Help us financially by purchasing from