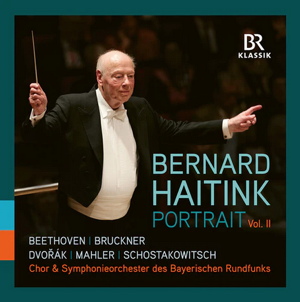

Bernard Haitink (conductor)

Portrait Volume II

Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra and Chorus

rec. 1981-2019

BR Klassik 900720 [9 CDs: 525]

This second volume of BR Klassik’s retrospective of Bernard Haitink’s work with the Bavarian RSNO isn’t quite as top-drawer brilliant as volume one was (review), but it’s still very welcome, and what’s good in it is very good.

You get a sense from some of their choices that they may have been rootling around in the archives rather than consciously selecting the best, as they did in volume one. While all of the performances captured here are interesting, several have their flaws, too. Take the Beethoven 9, for example. Much of it showcases Haitink’s unarguable gifts as a musical architect, and does so very well. Listen to the muscular, slow burning majesty of the opening, for example, which is the very embodiment of “old school”, and the assertive way the brass and timps punctuate the lyrical second theme of the first movement, or the pulverising climax that marks the beginning of the recapitulation. This is Beethoven that means business! That very weight becomes an issue in later movements, however. The Scherzo bounces, for example, but only just, and it doesn’t quite dance, a bit too overburdened by its own importance. Conversely, and counter-intuitively, the Adagio is too fast so that the tempo relationships between the movements are out of proportion, and while the finale is well played, it lumbers somewhat. The soloists are perfectly fine, though the recording balance favours them somewhat too much. So overall if you’re looking for Haitink in Beethoven 9 you’re far more likely to turn to his recordings from Amsterdam or London over this one.

Pacing is a bit of a problem in this 2011 Mahler 7, too, especially in the outer movements. The very opening is taken at a rather too stately pace, and it never quite finds the boosters required to power the main Allegro sufficiently. The same is true for the finale, which is strongly argued but, again, too stately in pace to have that sense of reckless abandon that it needs in order to convey Mahler’s sense of creation run riot. Both movements, however, are still moulded with complete surety and a marvellous sense of shape, and the instruments love every minute, each solo or spotlit moment is relished for all it’s worth, and that really helps the two Nachtmusik moments to twinkle. The recorded sound is really good here, too, with space and depth that seem to take to into and through the music – you’ll go a long way before you hear better recorded cowbells! – giving everyone their moment without ever losing the big picture. Moreover, Haitink’s pacing in all three middle movements is much more balanced, and that feeds into his shadowy Scherzo, too, which even manages the piece’s touches of humour. After the Concertgebouw and the Berlin Philharmonic, this is the third orchestra with which Haitink has recorded Mahler 7, a tally few conductors reach, and a suggestion that it’s a work that’s close to his heart.

The Bruckner selection is dependable and contains no surprises. In fact, it’s interesting how little Haitink’s readings change from his recordings elsewhere. The most straightforwardly successful of the set is No. 7 which was, let’s remember, the work with which Haitink took his final bow in 2019 (see review). Key to it is pacing, which reflects a lifetime of experience, and is much more certain – unarguable, even! – than in the examples above. Bruckner’s vast paragraphs unfold in a manner that makes it feel impossible to imagine them doing so in any other way. That’s particularly effective in the finale, which can sound problematically blocky in some performances, but here seems to breathe naturally, straining forwards and holding back in the right proportions. The playing is stellar, too, with a particular chapeau to the brass in the slow movement, who never sound doleful or miserable in Bruckner’s threnody to Wagner, but instead sound majestic and often even airborne.

Symphony No. 4 opens steadily, a little too slowly, perhaps; but the finale sounds surprisingly light on its feet, agile in places where elsewhere it can lumber. The Bavarian horns sound fantastic, not just in the opening solo, which reminds you how key the (German) sound of the horns is to Bruckner’s sonic world, but also in showpiece moments like the third movement trio. The strings are magisterial in the second movement. Weight is the default for the Te Deum, but there’s surprising lightness of touch in some of the solo moments. The passages with the violin solo sound truly lovely, making a very winning combination with the good solo team

Bruckner 8 plays to all of Haitink’s strengths, too. It’s huge, magisterial, and SLOW! You must look elsewhere if you want something nimble or period inflected. At the climaxes, however, it’s completely thrilling. The first movement’s sound is titanic, like a giant drawing breath, and the coda (in the Haas edition) has a terrible inevitability to it. But the Scherzo surprises us all by being as agile and pacy as the finale is vast and labyrinthine, yet still with a big sense of space in Scherzo’s B section which becomes almost cosmic. The trio sounds a little twee and unconvincing next to this, but then it often does. The playing in the Adagio is drop-dead-gorgeous playing in a movement that really suited Haitink: so clear, every note distinctively delineated, not a hint of aural sludge. When the brass come in to underpin the molten brown string sound, the effect is stunning. Sure, the finale is patchy, but it always is, and it carries a convincing sense of build through all the bitty episodes up to the blazing conclusion.

The loveliest surprise in the set comes from his performance of Dvořák’s Symphony No. 7. Haitink isn’t at all renowned for this sort of repertoire, but he takes to it with remarkable flair, helped perhaps by conducting an orchestra that had once been Rafael Kubelik’s. Of all Dvořák’s symphonies, this is the one that most lends itself to Haitink’s gifts for architectural insight and for building a grand musical paragraph, and you get both of those in spades in a terrific first movement that grips right from its swirling, brooding opening. The first orchestral tutti is sweetened by lyrical winds in its second subject, and Haitink shows his mastery in the final pages in the way the music speeds up to the coda and then slows down for the final bars, all sounding completely natural. The slow movement is expertly paced, and shaped with enough transparency to allow the solos to shine through the textures (and a passing bravo to the principal horn for his), while the Scherzo has uplift and bounce, preparing the way for a finale that feels driven and focused in every bar. In short, this is a triumph. The accompanying Scherzo Capriccioso lumbers a bit in comparison, but it’s saved by a second subject with a lovely, Ländlerish lilt.

Unlike Dvořák, Haitink most certainly was known for Shostakovich, and the two of his symphonies that feature here end the set with a real mark of quality. Haitink controls perfectly the vast span of the opening movement of No. 8 so that the great climax at the keystone of the arch feels both surprising and inevitable, the jagged shape of the motifs giving unarguable structural unity to the great piece. There is a similar sense of growth and retreat to the finale, which ends with surprisingly ethereal hush, and Haitink’s painterly touch enlivens the shorter movements, too. The second movement has a magisterial sense of threat to it, while the toccata feels like it’s driven by manic energy that never gets out of control. The slowly turning wheel of the Passacaglia has a gripping sense of scale in the cellos and basses, with haunted wind solos on top to give it poignant communicative colour.

The enigmatic No. 15 is all the more compelling because Haitink embraces the mystery without trying to solve it. The tempo for the first movement is on the stately side, which makes the grisly humour sound all the more grotesque. The brass in the second movement are haunting; the winds in the third are raucous and vulgar, while there is beguiling delicacy to the violins’ theme at start of finale. The ending is a disconcerting mix of chilly horror and empty irony, which is exactly what it should be.

So not everything is terrific, but the good things are very good indeed, and both of these BR Klassik volumes, taken together, serve as a wonderful testament to a conductor who had a longstanding, enormously successful relationship with this orchestra. All of the performances are in very good recorded sound, and all are live, but there is never a hint of audience noise, nor or applause. The accompanying booklet is rather feeble, with a little note about the artists but nothing about the music, which confirms that this isn’t aimed at newcomers to any of this repertoire. It’s aimed at Haitink’s admirers, which, let’s face it, means nearly all of us. It’s also a very economical way to pick up a lot of good performances at once. When you consider that the Dvořák 7 and Shostakovich 15 have recently been released separately at full price, this set becomes a viable bargain.

Simon Thompson

Buying this recording via a link below generates revenue for MWI, which helps the site remain free.

Contents

Ludwig van Beethoven

Symphony No. 9 [71:58] (rec. Philharmonie im Gasteig, Feb. 2019)

Sally Matthews (soprano), Gerhild Romberger (mezzo), Mark Padmore (ten), Gerald Finley (bass)

Anton Bruckner

Symphony No. 4 [68:05] (rec. Philharmonie im Gasteig, Jan. 2012)

Symphony No. 7 [63:48] (rec. Herkulessaal, Nov 1981)

Symphony No. 8 [88:06] (rec. Herkulessaal, Dec 1993)

Te Deum [23:30] (rec. Philharmonie im Gasteig, Nov 2010)

Krassimira Stoyanova (soprano), Yvonne Naef (mezzo), Christop Strehl (tenor), Günther Groissböck (bass)

Antonin Dvořák

Symphony No. 7 [37:36] & Scherzo capriccioso [12:05] (rec. Herkulessaal, March 1981)

Gustav Mahler

Symphony No. 7 [81:54] (rec. Philharmonie im Gasteig, Feb 2011)

Dmitri Shostakovich

Symphony No. 8 [64:47] (rec. Philharmonie im Gasteig, Sep 2006)

Symphony No. 15 [45:54] (rec. Philharmonie im Gasteig, Feb 2015)