Déjà Review: this review was first published in January 2007 and the recording is still available.

Benjamin Britten (1913-1976)

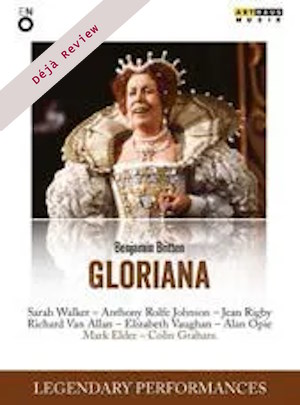

Gloriana, Op 53 (1953)

Sarah Walker (mezzo) – Queen Elizabeth I; Anthony Rolfe Johnson (tenor) – Essex; Jean Rigby (mezzo) – Lady Essex; Neil Howlett (bass) – Lord Mountjoy; Elizabeth Vaughan (soprano) – Lady Rich; Alan Opie (baritone) – Sir Robert Cecil

Chorus and Orchestra of the English National Opera/Mark Elder

Stage Producer: Colin Graham

rec. live, 1984, London Coliseum, London

Subtitles English, French, German, Spanish

Review of original release Arthaus Musik 102097 DVD

Arthaus Musik 109151 DVD [147]

This 1984 live English National Opera Gloriana is the first complete recording of the opera on DVD and could well be its earliest fully recorded performance. The first complete audio recording was made in 1992 by the Chorus and Orchestra of the Welsh National Opera/Charles Mackerras (Decca 4762593), while the first DVD to be released in 2006 was of Phyllida Lloyd’s film adaptation of the 1999 Opera North revival conducted by Paul Daniel (Opus Arte OA 0955D). The latter controversially cuts about one third of the opera and fuses performance and documentary. I refer you to my review for the details (see review).

Here from Arthaus we have the opera, the whole opera and nothing but the opera. Not just sitting you in the front stalls, however, as this DVD started life as a production for Channel 4 UK television directed by Derek Bailey. So there’s a fair mix of long shots taking in the stage set and court scene, the public spectacle, and close-ups, showing you the private emotions. Which is sensible because that’s what the opera is about, the conflict between the public persona of Elizabeth I as ruler and her private infatuation with the Earl of Essex.

For me the greatest strength of this performance is a then 37 year old Mark Elder’s magnificent realisation of the orchestration. It has more edge than either Daniel or Mackerras. Elder’s slightly pacier approach is a contributory factor. His overall timing before curtain calls is 143:39 against Mackerras 148:13. I’ll give just three examples of Elder’s skill. Those trumpet fanfares in the first scene are both resplendent and gaudy, prepared and spontaneous. They’re also heard first and last in the distance. This gives perspective to the procession, difficult to achieve on a stage where width is generally more noticeable than depth. But they also give perspective, as the opera does, to a reign: the Queen’s progress is to come and depart.

In scene 2, when the Queen sings of being wedded to the realm, the horns and contrabassoon backcloth symbolize what a weary burden this is at the same time as her heroic song of duty. Later, when Essex enters (tr. 7 27:08 in continuous timing) Elder creates a Puccinian frisson of tremolando strings which should be matched by the ardour of Essex’s ‘Queen of my life’ (27:35) but isn’t quite. The recorded sound, only in stereo, has excellent clarity if the somewhat fluorescent brightness of early digital recording.

The camera can be an unforgiving eye. Little errors of detail you might miss just watching a stage performance can irritate on DVD replay. In the first scene the stage direction – on page 17 of the vocal score – is that Essex is wounded because he turns at the sound of the Queen’s trumpeters. Not here (tr. 3 8:17). He’s just wounded in the course of a fight in which Mountjoy, or maybe Neil Howlett playing him, is a more stylish fighter! Sarah Walker’s Queen is an aristocratic presence rather wryly amused by this quarrel. In it Mountjoy sings ‘I flaunted nothing, you intruded’ (tr. 3 11:10) but this stage production has him getting his page to bind the Queen’s favour on his arm having already acknowledged Essex. I prefer Phyllida Lloyd’s production which has Essex lurking in the shadows, then coming out to address Mountjoy. After their reconciliation the Queen signals them to rise (tr. 6, 15:22) which they do, before she sings ‘Rise’ (15:25).

The second scene finds the Queen addressing her political adviser Cecil as ‘my pygmy elf’ (tr. 7 21:50), an authentic term but here rather kettle calling the pot black as they’re both about the same height. Essex later refers to Cecil as ‘the hunchback fox’ (tr. 21 65:59), yet he appears to have no deformity here. Only in Act 2 does he take to sporting a stick! Again Phyllida Lloyd’s production is more fastidious in such details. A key moment in the present one’s second scene finds the Queen showing Cecil ‘this ring’ (tr. 7 22:09), signifying the realm to which she is wedded, only Sarah Walker doesn’t really make a point of showing it at all.

Now comes the intimate audience with Essex and his two lute-songs. Anthony Rolfe Johnson sings with directness, clarity, brightness and lightness of tone with well rounded, graceful melismata in the second song ‘Happy were he’. There’s a trivial mistake: he sings ‘In contemplation ending all his days’ (tr. 10 31:44) rather than ‘spending’. I only mention it because this is the opera’s best known song. As for the contemplative Queen, we see her careworn and serene by turns. Elizabeth and Essex’s first duet (tr. 11 34:40) seems a kind of decorous musing in which neither barely looks at the other. What stays in the memory is the steely resolution of Walker’s final soliloquy statement, ‘I live and reign a virgin, will die in honour’ (tr. 13 39:23) to the splendour and burden of that orchestral brass again, especially the trombones, before movingly sinking to her knees in prayer.

Time to consider some crucial points of comparison. Is Sarah Walker’s portrayal of the Queen as fine as Josephine Barstow’s in the other recordings? Not quite. She gives an accomplished performance but Barstow stands apart more from the court and seems totally identified with the role. Being a soprano, for which voice Britten wrote it, helps. Her upper register has more density and, where appropriate, lightness and there’s more evenness across her range than Walker’s mezzo’s inevitably more regal lower register. Tom Randle is a more vibrant and sympathetic Essex than Rolfe Johnson. He has more ardour, energy and in the lute-songs subtlety and variation of delivery. There’s also an evident chemistry between him and Barstow in the duet. On the other hand Daniel’s orchestral backcloth seems in comparison more atmospheric than the third figure in the drama that Elder makes it.

In my earlier review I referred to ages of the cast in relation to those of the historical characters so it’s pertinent to do the same here. Elizabeth was actually 66, twice Essex’s age, when she sent him to Ireland. This puts a different perspective on their relationship, from both sides. With Barstow 59 and Randle 41 the age difference is more appropriate than Walker at 39 and Rolfe Johnson 44. To put it crudely, she’s too young and he’s too old. On the other hand, Van Allan at 49 is an excellent match for a Raleigh of 47, better than Bayley’s 39.

Act 2 Scene 1, the Queen’s visit to Norwich, is her happiest time in the opera. All finery and floral decoration. Mutual affection of Queen and subjects and those six choral dances, brilliantly written in an updated madrigal style for semi-chorus. The fast peal of the first, ‘Yes, he is Time’ (tr. 15 47:42) is formidably realized here. The third, ‘From springs of bounty’ (tr. 17 51:53) is also very quickly despatched given the marking ‘Gracefully swaying’ but its continual echoes between female and male voices are refreshingly revealed. The proceedings are directed by a fresh-voiced Adrian Martin as Spirit of the Masque, albeit he doesn’t have the poise and grace of John Mark Ainsley in the Mackerras audio recording.

In this DVD both the spectacle and symbolism of the dance strike home. Time as a dancer holds centre stage, then Concord, his loving wife. They join in an idyllic interlude of stillness, ‘each needeth each’ (tr. 16 50:50). The inference being Elizabeth isn’t complete without Essex and vice versa. In giving thanks Sarah Walker comfortably rises to her highest note in the opera, B flat (tr. 19 58:23) before the opera’s mantra, ‘O crowned rose’, appears in its most ecstatic, dazzling version (59:18).

Act 2 Scene 2 finds the all purpose set cleverly draped to become the garden of Essex’s house. Mountjoy and Lady Rich have an adulterous love duet, one step beyond that of Elizabeth and Essex. Joined by Essex and Lady Essex a plot begins to unfold in ensemble. Seeing this is more sinister than just hearing it. And you feel sympathy for Lady Essex who’s all the time in a minority of one in urging caution.

And it’s she who’s the victim in Act 2 Scene 3, the Whitehall ball. Essex decks her out in an outstanding gown. A step too far for Elizabeth, who steals it and puts it on to deride it and Lady Essex. But the gown in question isn’t the dazzling vermilion of Phyllida Lloyd’s production but only the pinkish hue of Colin Graham’s. Lady Essex’s plain dress isn’t markedly different. And on the Queen the gaudy one doesn’t noticeably appear, as she sings ‘too short’ (tr. 30 79:11). Nor are the general pauses in the score at 80:37, 42, 50 and 54 sufficiently marked to clarify what’s intended to be the Queen’s grotesque, halting exit, though the heavy brass venom is notable.

The dances themselves are very naturally played. The dancers fill the stage munificently. Essex, Mountjoy and their ladies lead the galliard, Elizabeth the lavolta. The morris dancer (tr. 28 77:10) doesn’t have ‘his face blackened’ (vocal score, p. 133) but whitened. I suppose more PC, even in 1984. Lively goosing, as well as some silky movement, in this from Robert Huguenin whom Britten buffs will recall as the original Tadzio in Death in Venice.

As in the first scene of Act 2, that of Act 3 has an echo chorus but this time it’s a fractious crack of dawn rumour exchanged between sopranos and contraltos as the Maids of Honour debate ‘What news from Ireland?’. Even with a combination of wide stage-shot and close-ups it’s pretty static here and Phyllida Lloyd was right to have swift panning and a claustrophobic dim lit environment. Essex is most distraught in Rolfe Johnson’s movingly emotive ‘forgive me’ (tr. 36 95:27). Walker’s Elizabeth caught nearly half dressed actually looks not weaker but harder and more resolute, so their second duet is bitter, the recall of their first with ‘Happy were we’ (tr. 36 100: 39) frozen in sorrow. Barstow and Randle make this a more beauteous, reflective elegy. Phyllida Lloyd makes better use than Colin Graham of the dressing-table song to adorn and prettify a Queen barely out of bed. What’s more striking in the present DVD is the energy of the orchestral accompaniment to Cecil’s report and the vehemence with which it backs the Queen’s decision to place Essex under guard.

It’s interesting to compare Act 3 Scene 2 in this DVD and the Mackerras CD. This scene relates the news of Essex’s escape and failed attempt at rebellion through the perspective of a group of old men outside a tavern in the City and a Blind Ballad Singer with gittern player who gets most of his news from a boy runner. On the CD Willard White as the Beggar has a richer, more velvety voice and more smilingly philosophical objectivity which extends to the roundedness of the response of the men’s chorus, but the rabble Essex boys are rather polite. Mackerras’s orchestra is lively but not as graphically so as Elder’s, whose timing for this scene is 9:35 against Mackerras 10:35. For Elder, Norman Bailey’s Beggar has more character with a somewhat more gnarled voice. The fellow feeling with the men’s chorus is less clear as they’re rather posh in attire but there is one telling visual image: the march past of the Essex boys, an army without arms and almost without clothing let alone armour, no threat to anyone.

In the final scene starkness is all. Everyone largely in black as if already in mourning for the condemned Essex. The tension boils over with the councillors in great alarm when Cecil suggests the Queen might pardon Essex. The Queen’s dilemma, ‘I love and yet am forced to seem to hate’, is movingly presented in soliloquy with unpitying directness by a pallid Sarah Walker (tr. 43 126:36). The trio of pleading Mountjoy, Lady Essex and Lady Rich (tr. 44 128:05), musically very severe because of the rich tone of the mezzo Lady Essex, is vividly gaunt when all kneel before the anguished Queen in view, singing what we know from her soliloquy are her thoughts as well as theirs. It’s Lady Rich who has the top C ‘Ah’ (tr. 45 134:28) when Elizabeth has signed the death warrant, but the Queen appears simultaneously to be letting out a silent heart-wrenching sigh.

Time to sum up and it’s difficult. If you’re looking to make a first purchase of Gloriana this should be your choice as it’s the closest recorded representation of the full operatic experience. But there are times, as I’ve indicated, when the other recordings offer a finer interpretation.

Michael Greenhalgh

Buying this recording via a link below generates revenue for MWI, which helps the site remain free

Other cast and details

Richard van Allan (bass) – Sir Walter Raleigh; Norman Bailey (bass) – A Blind Ballad Singer;

Adrian Martin (tenor) – The Spirit of the Masque; Malcolm Donnelly (baritone) – Henry Cuffe

Video Director: Derek Bailey

NTSC 4:3. Colour. Region Code All. PCM Stereo.