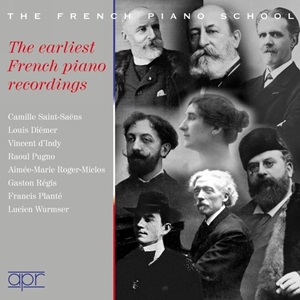

The Earliest French Piano Recordings

Various Composers and Pianists

rec. 1903-1928

APR APR7318 [3 CDs: 239]

In the latest addition to APR’s marvellous exploration of the French Piano School we are taken back to, if not quite the dawn of recording, then at least its earliest years. Even after four decades of collecting historical piano recordings I still find it remarkable that we can hear performances by pianists born 190 years ago and indeed three of the pianists on this wonderful anthology were born during Chopin’s lifetime. Chopin was just 25 years old when Saint-Saëns was born and he still had six years to live when Louis Diémer was born.

The recordings of Saint-Saëns, Raoul Pugno and Louis Diémer were collected together in a Marston set (Marston Records 52054-2 review) but those of Francis Planté were only available on one of their preferred customer Lagniappe CDs. Thankfully APR include them all along with other rarities, the recordings of Vincent D’Indy, Aimée-Marie Roger-Miclos, Lucien Wurmser and Gaston Régis.

Saint-Saëns was 68 when he recorded his first solos in just one session in 1904. They include includes three solos based on the music of three his concertante works, Africa, the Rhapsodie d’Auvergne and the first movement of the G minor piano concerto. Utterly blistering technique is the order of the day and high speeds; pianist Harold Bauer said that ‘he played everything too fast’ and he certainly races off the mark here though admittedly he mostly avoids the slower sections of the music. Even with the excellent transfer work done by Bryan Crimp on the original APR release and additional work by Andrew Halifax some of the music here is only just within the range that the G & T Company’s Paris machines could capture; parts of the right hand passages in the Rhapsodie d’Auvergne are barely audible but thankfully this is only in a few bars. He didn’t record again until 1919 and though he was now in his mid eighties his fingers show little change; the Valse mignonne appeared in both sessions and while the earlier version is frothier he is no slouch in 1919 and every bit as elegant. We may bemoan the lack of more serious fare but at least we can appreciate his command and panache in music that repays a committed performance and Saint-Saëns does that in spades. APR have omitted the vocal items for this release, and I confess that I do not miss them, but they have included the three pieces in which he collaborated with Gabriel Willaume. The Havanaise is familiar but neither the Élégie or La Déluge prélude are heard that often and Saint-Saëns proves himself a sensitive a chamber partner in these attractive works. The Havanaise was recorded two days later than the other 1919 items and Saint-Saëns does rather sound like he has been relegated to the adjacent room, Willaume’s rich steady tones now really taking centre stage.

I assume that many pianophiles were, like me, first introduced to names like de Pachmann and Rosenthal, Gabrilowitsch and Hambourg and others through Harold Schonberg’s book the Great Pianists (Gollancz 1978). I first read it at a time when the odd track might appear on an LP if you were lucky; for many years the only Saint-Saëns available was Africa on an International Piano Archives disc the Landmarks of Recorded Pianism (IPA117) – such a treasure! There was little hope of hearing the next pianist, Louis Diémer and his idiotically banal Valse, as Schonberg described it. Diémer’s name is now known in relation to the many students that passed through his classes; Alfred Cortot, Yves Mat and Robert Casadesus are the most familiar names from a long and distinguished roster. He was also an influential pianist though and a glance at imslp.org shows just 39 of the works dedicated to him including Franck’s variations symphoniques and the fifth concerto of Saint-Saëns. I am a little more forgiving than Schonberg and enjoyed the grande valse de concert for the frothy morsel it is and can only marvel at Diemer’s effortless and strikingly clean finger work. The piece is cut dramatically and though there are a few more bars in the later version the lyrical trio and a series of even more extended scale runs in the reprise are missing; there is still more than enough to show what a technician Diémer must have been. This is also evident in his Caprice de concert, Le Chant du Nautonier, the song decorated with enviably swift and polished arpeggios and a feather-light scherzo at its heart. Both recordings are cut though Diémer includes a little of the brief introduction in the 1906 recording. The later versions are both very dry with hardly any pedal and though the sound is better their admittedly slight musical value is exposed more; the sailor singing this song had probably been a bit too liberal with the wine. Benjamin Godard’s chromatic waltz is very much in the same world as the Diémer pieces, all the more so with the little alterations that Diémer makes – adapted left hand, passages in octaves. The popularity of Mendelssohn’s spinning song is clear when you notice that four of the eight pianists here recorded it and by the time Francis Planté added his version to the list it had been recorded nearly forty times – and many more if you include piano rolls. It is a supple as would be expected under Diémer’s fingers. The Chopin nocturne that follows is relatively quick though I have heard faster versions; even so Diémer shows himself to be more than a speed merchant.

Vincent D’Indy is known as a composer though little of his music is heard in the concert hall; perhaps his Symphony on a French Mountain Song very occasionally and some pianists have taken up his huge Sonata in E. He was a decent pianist however and had studied with Diémer and his predecessor Antoine Marmontel (1816-1898). He recorded four of his Tableaux de voyage, his musical diary of his walking trips in Germany which have more substance than Diémer’s pieces though I note a review that describes a recorded selection as uninspired in the extreme. Lac Vert was the only overlap so perhaps the reviewer needed to hear this happy selection which is full of life and is crowned by the vigorous depart matinali demonstrating quite clearly that d’Indy was no slouch at the piano. The Danses rythmiques is even more interesting with its rondo dance theme in 14/16…and 10/8, 12/16 and other time signatures, bookending a valse grotesque marked completely detached and a lyrical section marked to the beloved. D’Indy is adept at the rapid changes of the main dance and is perfectly grotesque and detached when needed.

Raoul Pugno had a successful career both as a soloist and as recital partner to Belgian violinist Eugène Ysaÿe though after studies with Chopin pupil George Mathias and a successful early début he spent his time as an organist and composer before restarting his piano career at the age of 41, just a decade before he made the series of discs released here. He certainly displays a more varied repertoire than any of the others pianists here though it rests on the romantics – even the Handel and Scarlatti selections are highly romanticised. Many pieces here attest to Pugno’s fully rounded technique with dazzling playing in the Liszt Hungarian rhapsodie, Weber Rondo and Massenet’s mad waltz, a piece that was dedicated to him. He shares the crystalline fingerwork of Saint-Saëns and Diémer but with more muscular playing as displayed by the Liszt, Mendelssohn Hunting song and Chabrier scherzo-valse. His Chopin selection includes an extremely fast A flat waltz that one might ascribe to the limitations of time were it another pianist. I get the feeling that this was probably how he normally played it; it was not unusual to get faster in more virtuosic sections and the more lyrical sections are no faster than I have heard others play them and he is absolutely in control in the even faster coda. The berceuse is fluent and it is only in the thirds that it sounds a little hard edged and the outer sections of the F sharp minor nocturne are taken quite slowly though Pugno apparently inherited this idea from his teacher. It may be a little unusual but he does vary the speed a little throughout so it doesn’t sound lugubrious. More striking to me is funeral march from the second sonata; Pugno is rather stentorian in the march and plays fortissimo at its return only to die to a hushed tone that continues to the end. This ending and the brief trio show just what a singing tone Pugno had.

The only female pianist to grace this collection is Aimée-Marie Roger-Miclos; Cécile Chaminade recorded several sides in 1901 that are available on APR5533 and in the booklet these are described as a special case. One wonders if there will be a further release in the French Piano School series that will include them in the spirit of completeness? Roger-Miclos was born in 1860 and studied with Henri Herz. She married twice and the earliest of her recordings date from the year of her second marriage to musician Louis-Charles Battaille. The booklet says that after 1905 she maintained a very low public profile which possibly explains why she made no further recordings after 1906 despite living until 1951. Considering the fleet fingers we have heard so far Roger-Miclos is relatively restrained; she is not far behind Pugno in the figuration of the A minor Hungarian rhapsodie, curtailed to nearly half the length of Pugno’s version and sparkles in the Mendelssohn items and the Chopin D flat waltz but it is not the gossamer of Diémer. She finds more time for melody in the nocturne op.15 no.2 though in spite of Pugno’s slower opening he comes in at 3.36 to Roger-Miclos’ 3.35. She is a little stiff in the outer sections of the C sharp minor waltz, her rubato getting slightly in the way of the dance but is delightful in the runs, characteristically faster. Some may prefer her more relaxed take on Mendelssohn’s E minor scherzo though I would plum for the more frenetic but also cleaner Pugno recording. She ends with Schumann’s Traumenswirren and like most of her recordings it is well executed without being outstanding; the booklet relates George Bernard Shaw’s description of her playing in her cold, hard, swift style having previously said that he admired her in the way that I admire the clever people who write a hundred and eighty words a minute with a typewriter, neither of which seem to fit with the relaxed, lightweight and pleasant playing on these records; I wonder what he would have made of Diémer or Pugno?

With the help of the International Piano Archives in Maryland and collector Jonathan Dobson APR have found a real rarity in Gaston Régis, a Nimes-born pianist who studied under Charles-Wilfrid de Bériot (1833-1914) son of the violinist Charles-Auguste de Bériot. Régis settled in Oran in Algeria, remaining there until his death in 1935. He met and performed on two pianos with Saint-Saëns and it was in Algeria that he recorded these tracks of his friend’s music along with a relative rarity, the tarantelle by Chopin. I would have liked to hear more as he appears to be an unaffected and tasteful pianist with charm and plenty of technique, rivalling Saint-Saëns’ elegance and suave playing in the valse mignonne and bringing those qualities to bear in a fine tarantelle and two dance movements from Saint-Saëns seldom hear Suite op.90. The piano sound of these discs is a little more recessed than the others here but the detail still shines through.

Francis Planté was probably one of the greatest French pianists of the 19th century and it is sad to think that were it not for the fact that he abandoned public appearances in 1900 he might have made records at the same time as Diémer or Pugno. Like d’Indy he was a pupil of Marmontel and graduated from the Paris Conservatoire at the tender age of 11 and began a highly successful career, attracting plaudits from all sides, that continued, with the occasional extended absence à la Horowitz, into his eighties. Having declared in 1900 that he would never appear before the public again he kept his promise when he began to perform again in 1915, getting round his vow by performing behind a screen; there must have been something of de Pachmann the Chopinzee in him. Determined to capture Planté on disc while they still could engineers travelled to his villa at Mont-de-Marson, the resulting discs being the eighteen pieces on disc three of this set. Schonberg was scathing about these recordings; it is a little embarrassing to discuss them he writes continuing his playing is spasmodic at best. One wonders if he actually heard them all or based his judgement on one or two that he managed to track down? Whatever the case there is lots of genuinely fine playing amongst them starting with the Mendelssohn pieces that start the set. The Hunting song is undoubtedly slower than he would have taken it even a decade earlier but this is not stumbling, spasmodic playing, rather it has strength and vigour combined with a wonderful delicacy in the faster music. His Spinning song may be the slowest on this disc, almost thirty seconds slower than Pugno but with his clarity and sense of direction it does not sound slow. Perhaps the E minor Scherzo is a little cautious and halting but I have not yet heard the uncontrollable power that Schonberg describes. The Chopin études tax him more and these would not stand up to any of today’s steel fingered virtuosi but for the most part he still gives good accounts of them, even forgiving the smashed chord at the end of op.10 no.7 and the cry of merde! that follows it. His butterfly is a little heavy handed occasionally but he is controlled enough to bring character and light and shade to even the toughest sections of op.10 no.4 or op.25 no.11 and in op25.no.1 he turns in a performance that puts a very slightly younger French pianist, Auguste de Radwan to shame (Sakuraphon SKRP78015-16 review). I rather like his Schumann; the F sharp major romance is a little fast but the melody really sings and his tone in the second section is beautiful. Any doubts about his technique are banished by the romance from the four pieces op.32 and Debussy’s transcription of at the Spring, originally a four hand work which are both supple,energetic and full of character. The Sérénade de Méphistophélès swaggers convincingly and listening to this without context I doubt one would consider this an old man playing. I am less convinced by Planté’s own transcription of the famous Menuett from Boccherini’s E major quintet; though for the most part it skips innocently along it is marred by mis-struck left hand notes and whacking accents at the end of phrases. His transcription of the Gluck Gavotte, more elaborate than the popular arrangement by Brahms, is more attractive as long as you ignore the hefty ritardandi at every verse-end. The main difference in Planté’s arrangement is in the trio where each repeat is accompanied by a running left hand, smoothly executed by Planté. Schonberg may not have heard all of the these recordings and its a guarantee that he never heard them in such clear, rich sound but his judgement still seems unfair after giving these a decent hearing. What a shame that his unpublished discs have never surfaced; they include the finale from Liszt’s 6th rhapsodie, Schumann’s Vogel also Prophet and the first movement of Weber’s C major sonata.

Bringing up the rear is another rare name, Lucien Wurmser. I knew of him from many years back when I got a 10” disc of piano and dramatic selections by Yvonne Arnaud on which she played his Impromptu; her performance can be found on youtube. Other than that I was ignorant of the man himself and indeed the booklet acknowledges that little biographical information is available. He was born in Paris in 1877 and was granted a long span, dying in 1967. Along the way he graduated from the Paris Conservatoire where he was another pupil of Charles de Bériot, played alongside Raoul Pugno, toured as the conductor for ballet dancer Anna Pavlova’s Australian tour, wrote film scores and, in addition to the pieces on this disc, recorded chamber music by Schumann, the piano trio op.110, and Beethoven, the quintet for piano and wind op.16.

His recordings reveal him as an elegant pianist with a lovely tone shining through the swish and hiss of the 1911 discs, none so clearly as the pastorale variée in which he omits the triplet variation, presumably for reasons of space. The cadenza seems to confirm that the authorship is doubtful; it sounds a bit too modern for Mozart. He wants to enjoy the opening of the B minor mazurka a little too much though it is sensitively done and is suitably energetic in the more upbeat sections. I prefer his C sharp minor to the version by Roger-Miclos; her little scurries through the quavers of the opening distort the time a little too much and Wurmser is more lilting. He manages to sustain the slow tempo that he adopts for the A flat waltz though not surprisingly picks up the tempo when more decorative figuration enters. I like his two salon miniatures which could have come from the pen of Chaminade; petite aubade with its serenade morning over a gently syncopated accompaniment and the flowing impromptu that has moments of early Debussy. His playing is supple and suave, quietly flamboyant without the extrovert playing of Diémer or Pugno. Two Schubert encores finish his set; Fischoff’s straightforward transcription of the Rosamunde ballet music – the intricate Godowsky and Pouishnoff versions were far in the future – and the once ubiquitous Tausig transcription of the four hand marche militaire. The booklet notes that in addition to the chamber works alrady mentioned he recorded thre Debussy piano solo and Le Moulin and the Fantasie for piano and orchestra by Albert Perilhou; that would be a nice future release for this series.

I am very impressed with the transfers here, Bryan Crimp, Roger Beardsley in making the transfers for previous releases and Andrew Hallifax in the additional restoration and pitch stabilization have done a great job dragging a decent sound out of these troublesome early discs. I won’t be without my Marston set; I feel that Ward Marston finds more music in the Saint-Saëns such as the opening of the rhapsodie d’Auvergne that is just that more audible in those transfers and he tidies up the distortion in the opening chords of Africa. Impressive though that set was for pitch stabilization on the Pugno discs the software has presumably come on since 2008 and there is even less wobble in the sound in these new transfers. It is a minor difference and collectors could be very happy with either set though I will be keeping both. The Marston has Grieg’s complete recordings as well as the vocal items missing from the Saint-Saëns and Pugno, assuming it is Pugno accompanying Maria Gay in his song page d’amour, Debussy accompanying Mary Garden and an ultra rare disc of Massenet accompanying an aria from his opera Sapho. The treasures collected here make this perhaps the most significant addition to APR’s French Piano School series; these are early enough to represent the pure French style, mostly uncontaminated by other piano schools. It is ironic really that it was the rapid growth of the recording industry in the years following these discs, an industry that allows us to enjoy the playing of Saint-Saëns and his fellow musicians, that ultimately helped to dilute national playing styles. For pianophiles this is self recommending release and anyone with any interest in historical piano playing should snap up this wonderful set.

Rob Challinor

Buying this recording via a link below generates revenue for MWI and helps us keep free access to the site

Contents

CD1

Camille Saint-Saëns (piano)

Camille Saint-Saëns (1835-1921)

G&T Co. Paris acoustic recordings. rec. 26 June, 1904

Africa Fantasie, abbreviated for piano solo Op.89

Valse mignonne Op.104

Valse nonchalante Op.110

Piano Concerto No.2 Op.22 andante sostenuto abbreviated for piano solo

Rhapsodie d’Auvergne Op.73 abbreviated for piano solo

G&T Co. Paris acoustic recordings. rec. 24 November, 1919

Rêverie du soir (à Blidah) – Suite Algérienne Op.69 No.3

Marche Militaire Française – Suite Algérienne Op.69 No.4

Première Mazurka Op.21

Valse mignonne Op.104

Prélude from La Déluge Op.45 arr. Violin and piano

Élégie Op.143

G&T Co. Paris acoustic recordings. rec. 26 November, 1919

Havanaise Op.83

Gabriel Willaume (1873-1946) (violin) in Opp.45, 143 and 83

Louis Diémer (piano)

G&T Co. Paris acoustic recordings. rec.1904

Louis Diémer (1843-1919)

Grande valse de concert Op.37

le Chant du Nautonier Op.12

Benjamin Godard (1849-1895)

Valse No.5 Valse Chromatique Op.88

Felix Mendelssohn (1809-1847)

Song without Words Spinnerlied Op.67 No.4

Frédéric Chopin (1810-1849)

Nocturne in D flat major Op.27 No.2

G&T Co. Paris acoustic recordings. rec.1906

Louis Diémer (1843-1919)

le Chant du Nautonier Op.12

Grande valse de concert Op.37

Vincent D’Indy (piano)

HMV Hayes, Middlesex; acoustic recordings 7 June 1923

Vincent D’Indy (1851-1931)

Tableaux de voyage Op.33

No.4 Lac vert

No.5 Halte, au soir

No.6 La poste

No.9 Départ matinal

Danses rythmiques No.2 from Poème des Montagnes Op.15

CD2

Raoul Pugno (piano)

G&T Co. Paris acoustic recordings. rec. April, 1903

George Frideric Handel (1685-1759)

Gavotte and variations from Suite in G major HWV.441

Domenico Scarlatti (1685-1757)

Sonata in A major K.24

Raoul Pugno (1852-1914)

Impromptu-Valse

Frédéic Chopin

Waltz in A flat major Op.34 No.1

Franz Liszt (1811-1886)

Hungarian Rhapsodie No.11 S.244 No.11

Carl Maria von Weber (1786-1826)

Rondo Brilliante in E flat major Op.62

Felix Mendelssohn

Song without words Op.19b No.3 Hunting song

Raoul Pugno

Sérénade à la lune

G&T Co. Paris acoustic recordings. rec. Nov, 1903

Frédéric Chopin

Nocturne in F sharp minor Op.15 No.2

Felix Mendelssohn

Song without words Op.67 No.4 Spinning song

Jules Massenet (1842-1912)

Valse folle

Emmanuel Chabrier (1841-1894)

Pièces pittoresques No.10 Scherzo-valse

Raoul Pugno

Trois airs de ballet No.1 valse lent

Frédéric Chopin

Impromptu No.1 in A flat major Op.29

Berceuse Op.57

Piano Sonata No.2 Op.35 Marche funèbre

Felix Mendelssohn

Scherzo in E minor Op.16 No.2

Aimée-Marie Roger-Miclos (piano)

Fonotipia recordings, Paris; acoustic recordings Sept, 1905

Benjamin Godard (1849-1895)

Mazurka No.4 from suite de danses anciennes et modernes Op.103

Frédéric Chopin

Waltz Op.64 No.1

Felix Mendelssohn

Song without words Op.67 No.4 Spinning song

Rondo capriccioso Op.14 (abridged)

Franz Liszt

Hungarian Rhapsodie No.13 S.244 No.13 (vivace only)

Hungarian Rhapsodie No.11 S.244 No.11 (andante sostenuto to end)

Fonotipia recordings, Paris; accoustic recordings 15th Nov, 1906

Frédéric Chopin

Nocturne in F sharp major Op.15 No.2

Waltz in C sharp minor Op.64 No.2

Felix Mendelssohn

Scherzo in E minor Op.16 No.2

Robert Schumann (1810-1856)

Traumenswirren No.7 from Fantasiestücke Op.12

Gaston Régis (piano)

Gramophone Company, Algiers: acoustic recordings 21st July, 1921

Frédéric Chopin

Tarantelle Op.43

CD3

Camille Saint-Saëns

Suite pour le piano Op.90 No.2 menuet

Suite pour le piano Op.90 No.3 gavotte

Valse mignonne Op.104

Francis Planté (piano)

French Columbia, Saint-Avit, Mont-de-Marsan; electric recordings 4th July, 1928

Felix Mendelssohn

Song without words Op.19b No.3 Hunting song

Song without words Op.62 No.6 Spring song

Song without words Op.67 No.4 Spinning song

Song without words Op.67 No.6 Serenade

Scherzo in E minor Op.16 No.2

Frédéric Chopin

Étude in C sharp minor Op.10 No.4

Étude in G flat major Op.10 No.5 black keys

Étude in C major Op.10 No.7

Étude in A flat major Op.25 No.1 Aeolian harp

Étude in F minor Op.25 No.2

Étude in G flat major Op.25 No.9 butterfly

Étude in A minor Op.25 No.11 winter wind

Robert Schumann

Romance in F sharp major Op.28 No.2

Romance in D minor Op.32 No.3

Robert Schumann arr. Claude Debussy (1862-1918)

Á la Fontaine (Am Springbrunnen) Op.85 No.9

Hector Berlioz (1803-1869) arr. Ernest Redon (1835-1907)

Sérénade de Méphistophélès from La Damnation de Faust

Ridolfo Luigi Boccherini (1743-1805) arr. Francis Planté (1839-1934)

Célèbre Menuet de Boccherini

Christoph Willibald Gluck (1714-1787) arr. Francis Planté

Gavotte from Iphigénie en Aulide

Lucien Wurmser (piano)

Gramophone Company, Paris: acoustic recordings April and May, 1911

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791)

Pastorale variée K.anh.209b (probably spurious)

Frédéric Chopin

Mazurka in B minor Op.33 No.4

Waltz in A flat major Op.69 No.1

Waltz in C sharp minor Op.64 No.2

Lucien Wurmser (1877-1967)

Petite aubade

Impromptu

Franz Schubert (1797-1828) arr. Robert Fischoff (1856-1918)

Rosamunde ballet music D.797 No.9

Franz Schubert arr. Karl Tausig (1841-1871)

Marche Militaire in D flat major D.733 No.1