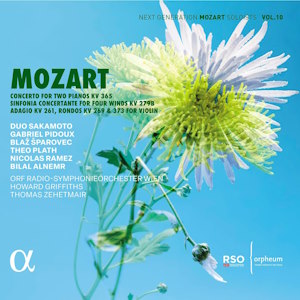

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791)

Piano Concerto No. 10 for 2 pianos in E flat, K365

Rondo for Violin and Orchestra in B flat, K269

Adagio for Violin and Orchestra in E, K261

Rondo for Violin and Orchestra in C, K373

Sinfonia concertante for four winds in E flat, K297B

Piano Duo Sakamoto (pianos)

Bilal Alnemr (violin), Gabriel Pidoux (oboe); Blaž Šparovec (clarinet); Theo Plath (bassoon); Nicolas Ramez (horn)

ORF Radio-Symphonieorchester Wein/Howard Griffiths, Thomas Zehetmair

rec. 2021/22, ORF RadioKulturhaus, Großer Sendesaal Wien, Austria

Next Generation Mozart Soloists Vol 10

Alpha Classics 1087 [72]

This is volume 10 of Alpha’s ‘Next Generation Mozart Soloists’ series. I select my favourite and unfavourite tracks. High among the former is track 1, the first movement of Mozart’s only purely conceived Concerto for 2 pianos composed for himself and his sister ‘Nannerl’. Here are novelty, variety and entertainment – and also the determination that the pianists should upstage the orchestra. The latter wavers between grand tutti flourishes, strings with quipping appoggiaturas and emphatic accents (tr. 1, 0:09), searching out an individual lead in the following tutti sporting a motif anchored on six identical quavers (0:34) which the wind instruments readily copy. The six quavers expand to eight in the first violins (0:58) against which the second violins and violas are more purposively thematic but the two horns steal the limelight with a delightful motif all their own (1:04). Through such intricacy, well conveyed by Howard Griffiths conducting the Vienna ORF Radio Symphony Orchestra, we hear how the introduction gradually forms a coherent, confident exposition. Now come the pianists, both hands playing in octaves, an electrifying opening by the sisters, Piano Duo Sakamoto. Then how much clearer and beguiling are the appoggiaturas, and the added ornamentation is presented in turn, solo, by first and second pianos. Soon the pianists bring new material (2:37), tripping then scampering downwards in turn. Our soloists’ interchange is sensitive yet vibrant, their invention seems inexhaustible. But the orchestra hasn’t entirely disappeared; e.g.the oboes echo the pianos’ nostalgic melodic descents in turn (from 5:09). The recap of the opening theme in the minor mode doubles as development (6:20), quickly dispelled by the pianists’ animation. Mozart’s cadenza begins with the soloists’ opening blaze, the second piano now particularly bullish yet also reintroducing that balmy descending phrase (9:19). The Sakamoto sisters are like twins, for ever mimicking yet also sustaining one another.

I compare this with two sisters also of Japanese lineage, Mari and Momo Kodama, recorded in 2023 with L’Orchestre de la Suisse Romande conducted by Kent Nagano (Pentatone PTC 5187202). Nagano’s introduction is brighter, suaver, but with less exploratory growth than Howard Griffiths’. The Kodamas’ entry has less impact but their ornamentation is neat and their interplay bubblier. The Sakamotos’ less brilliant but calmer, more graceful, approach makes melodic descents more magical and the minor key visit more telling.

Of the three pieces for violin and orchestra, my favourite is the Adagio in E for its greater presence and character in its arioso-like solos, distinctive as the highest lines and are often unexpectedly airborne by the strings. Bilal Alnemr accomplishes this role with distinction, aided by playing on a Lorenzo Carcassi instrument of 1774 loaned to him by Michael Barenboim. For me, Thomas Zehetmair’s orchestral introduction is a shade too fulsome but Alnemr’s response has a sensitive blending of firm focus and sweetness. Accordingly, it’s appropriate he’s allowed to introduce the second part of the first theme (tr. 5, 0:52) and, while the orchestra starts a frolicsome third part (1:17), Alnemr embellishes it with more substance which the orchestra in turn develops exquisitely. His central extended passage (2:13) illustrates coping in sadder times. The return of the opening is capped by a cadenza. Alnemr supplies his own which fixes your attention on the first theme then brings a new focus on Vivaldi bird-call-like phrases of exploration before deferring to, and enhancing, earlier expressions of contentment.

I compare this with Renaud Capuçon, soloist and here leader of L’Orchestre de Chambre de Lausanne recorded in 2022 (Deutsche Grammophon 4864067). Timing at 6:51 against Alnemr’s 5:27, Capuçon is more relaxed yet still flowing. He has a sunnier, more cantabile sweetness, a more golden tone and suaver contrast of registers. The orchestral contributions are more stylish, the bass less heavy. Alnemr, however, makes his mark in two aspects: his central section has a more sorrowing impact; his cadenza is more imaginative than the simpler one by Robert Levin Capuçon plays, with a more direct recall of the opening theme and low and high tessitura extemporisation around this, leading to a neat resolution.

Now my unfavourite track! The Sinfonia Concertante for four winds comes in the Mozart Neue Ausgabe with works ‘of doubtful authenticity’, its source a 19th century manuscript, some of which lacks Mozart’s style and quality, but the virtuoso wind solos sound the real thing. After a short, rather demure first theme opening from the strings the sun comes out with the orchestra’s oboes and horns (tr. 7, 0:14). Benign progress gets stuck in a chain of repeated phrases. A second theme begins gracefully (1:25) but is peremptorily thrust aside for more ostentation and then folksy jollity. For exposition coda (2:01) comes a cluttered return of oboes and horns repeating the same note against tremolando violins and the lower strings taking up the first theme start. Fortunately, the wind soloists recap the first theme (2:37) with the melody gorgeously interchanged between the four and for a worthy development (4:08) they add extensions of semiquaver runs. The second theme recap blossoms as the oboe releases it from its shell (4:52). More cavorting semiquavers lead us now naturally to the quartet together with the folksy end of this theme. Even the three elements of the coda are articulated with more clarity and purpose. The second theme earlier jolly close is more suitable as the soloists’ cadenza, capped by their lovely postlude (12:02).

I compare this with the Academy of St. Martin-in-the-fields/Neville Marriner recorded in 1983 who play a reconstruction by Robert Levin (Philips 4111342, now reissued by Presto). This introduces the soloists from 0:14, integrating their contributions without orchestral rambling. Repetitions of the same notes are banished, so the return of the first theme only against upper strings’ tremolando makes both elements more potent. Tuttis are fewer. The soloists’ cadenza is more flauntingly virtuosic. Marriner times at 9:30 against Zehetmair’s 12:53. It is altogether a more satisfying experience, but two caveats: Levin restoring Mozart’s original scoring of flute, oboe, horn and bassoon makes a less exhilarating grouping than oboe, clarinet, horn and bassoon; Marriner takes a more energetic approach which misses the more glowing joy of making melody of the excellent Alpha soloists.

Michael Greenhalgh

Buying this recording via a link below generates revenue for MWI, which helps the site remain free