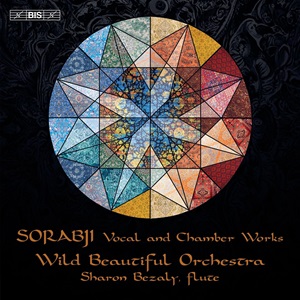

Kaikhosru Shapurji Sorabji (1892-1988)

Vocal and Chamber Works

Sharon Bezaly (flute)

Wild Blue Orchestra/Taylor Gonzales

rec. 2022/2023, Lamont School of Music, University of Denver, Colorado, USA

BIS BIS2683 SACD [79]

Pianist Chappell Kingsland, who appears in most of the thirteen works on this disc, has supplied a detailed and helpful booklet essay. The opening remarks remind us that Sorabji ‘is known more for his reputation than for his music’; and ‘it was a matter of pride that his works were generally too long or too complex for the public’.

This programme gathers pieces which last from fifty seconds (Désir éperdu) to sixteen minutes (Il tessuto d’arabeschi). Frammenti aforistici traverse four movements in less than ninety seconds. Those are mere bagatelles by Sorabji’s standards.

Sorabji believed that almost no performers would have a really convincing ability to play his works as he wanted. That, he must have assumed, would have led to strong, even vile criticism, especially before the last war. But the players here would not cause him problems. In my time, I have been involved in performing highly complex music, both ancient and modern. Yet I am truly astonished by the way these musicians not only get their heads around Sorabji’s music but make it sound musical. Much of this must come to down to the dedication of Chappell Kingsland and Marc-André Roberge, who have prepared many of the editions.

Take Il tessuto d’arabeschi. For almost its entire length, it tosses about in highly complex and dense counterpoint which, even after a few hearings, seems hard to assimilate. But the composer often remarked, and it is relevant to this piece, that the music could be like a seamless Persian rug. Now, we have one. As I look at its intertwining patterns, it is clearly impossible to see where one line ends and another begins, and how they fully relate. Standing back, they create an intoxicating vision of colour and configuration. Even so, the music does not necessarily make easy listening. In fact, it might try your patience unless you listen with very open ears. To a certain degree, this comment applies to other works recorded here.

As for the harmonic language, I played some of the songs to an ex-pupil just graduated from the Guildhall School of Music. We both felt, especially in the earlier songs, that there is a stylistic cross between Schoenberg and Debussy. So, although this is not atonal, the key is never clear. The harmonies shift from one chromatic chord to the next like a kaleidoscope. Just consider Le mauvais jardinier (completed by Chappell Kingsland), and the two versions of the Frammento cantato. Incidentally, the latter version requires two players at one organ!

The language can also be voluptuous. It reminds me of some almost erotic Arabic poetry. Arabesque falls into that category. Indeed, all of the early works have this characteristic. But it can sometimes be too elaborate. Chappell Kingsland tells us that the piano writing in the Trois poèms du Gulistan de Sa’di is reminiscent of Sorabji’s Nocturnes. It seems to me that the highly decorated and complex piano writing in this cycle totally dominates the rather uninteresting vocal line, which seems to bear almost no relation to it. The poems about male love – but not, I feel, homoerotic – cry out for some word painting, but there is almost none. The only relief from the constant elaboration is in the third song, La fidelité, which has a longish section in quasi-recitando.

That is one of three song cycles, which all last about a quarter of an hour. Imagine this high-density piano writing moved to a chamber orchestra (including piano) – that is the setting for Cinque sonetti di Michelangelo Buonarroti, five poems performed without a break, about love between men. This represents Sorabji’s first orchestral score ever recorded. One cannot doubt the passion behind the complex counterpoint and vocal line. Still, I have to admit that I have really never encountered any music quite like this. It is taking some time to come to terms with it. The differing layers of the orchestration, we read, represent certain characteristics to be found in the poems.

The disc ends with a more approachable work, Movement for voice and piano. The voice acts as a vocalise across the continuous, Debussian piano writing. Some of you will think the music may be more akin to Messiaen, capped by a dreamy and lyrical legato line of great beauty. This is perfect late-evening music, different from much else on the disc.

There is a lot here which will fascinate, and a lot that might frustrate even the most open-minded listener. Nonetheless, one thing one can say is that it is of a personality quite unique in twentieth century music. The marvellous performers are telling us to take this music seriously.

Gary Higginson

Buying this recording via a link below generates revenue for MWI and helps us keep free access to the site

Contents:

1. Désir éperdu for piano (1917)

2. Il tessuto d’arabeschi for flute and string quartet (1979)

3. Le mauvais jardinier for voice and piano (1918-1199)

4. Frammento cantato for baritone and piano (1967)

5. Fantasiettina atematica (1981)

6-8. Trois poèmes for soprano and piano (1941)

9-13. Cinque sonetti di Michelangelo Buonarroti (1923)

14. Arabesque for soprano and piano (1920)

15. Benedizione di San Francesco d’Assisi (1973)

16-18. Trois poemès du Guilstan de Sa’di (1926/1930)

19. Frammenti aforistici for piano (1977)

20. Frammento cantato for baritone and organ (1967)

21. Movement for voice and piano (1927-1931)

Performers:

Chappell Kingsland (piano and organ) [tracks 1, 3, 4, 6-8, 14-15, 19, 20]

Sharon Bezaly (flute), Wild Blue Orchestra/Chappell Kingsland [track 2]

Sharon Harms (soprano) [tracks 3, 21]

Andrew Garland (baritone) [tracks 4, 9-13, 15, 20]

Sarah Bierhaus (oboe) [track 5]

Julie Thornton (flute) [track 5]

Jeremy Reynolds (clarinet) [track 5]

Zoë Spangler (soprano) [tracks 6-8, 14]

Wild Blue Orchestra/Taylor Gonzales [tracks 9-13]

Emily Walker (organ assistant) [track 20]

Christopher Grundy (baritone) [tracks 16-18]

Bryan Chuan (piano) [tracks 16-18, 21]