Ernst von Dohnányi (1877-1960)

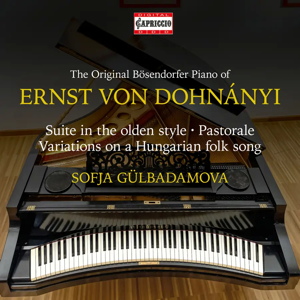

The Original Bösendorfer Piano of Ernst von Dohnányi

Waltz from Delibe’s Coppélia (arr. Dohnányi, 1925)

Pastorale on a Hungarian Christmas Song (1920)

Suite in the Olden Style, Op 24 (1913)

Variations on a Hungarian Folksong, Op 29 (1917)

Three Pieces, Op 23 (1912)

Treasure Waltz from Strauss’s The Gypsy Baron (arr. Dohnányi, c.1930)

Sofja Gülbadamova (piano)

rec. 2022, Museum of Music History, Budapest, Hungary

Capriccio C5519 [68]

The history of the piano is littered with ideas to improve it. Several have been successful and have gradually been introduced into the design; extended ranges, a cast iron frame and Érard’s double escapement action which allowed for fast repeated notes are just three of the better ones. A curved keyboard to bring all the notes within easy reach has never caught on though there have been a few attempts, one by Frederick Clutsam among them. Clutsam was born in New Zealand – the booklet describes him as an Australian musician and inventor but it appears he didn’t move to Melbourne until 1891 when he was in his early twenties. In 1907 he registered a semi-circular keyboard that attracted enough attention to be adapted and sold in pianos manufactured by Grotian, Berdux and, with Dohnányi’s promotion, Ibach. Dohnányi’s first documented use of this piano in concert was in 1909 and the booklet notes that his concert programs up until 1913 often mentioned the use of the keyboard with the Clutsam adaption. Bösendorfer started adding it to some of their pianos in 1910 and they made at least one, perhaps two for Dohnányi; the one which he used at his Budapest home until he emigrated to America in 1944 now sits in the Museum of Music History in Budapest and was used for this recording. Sofja Gülbadamova has already recorded a good deal of Dohnányi’s music including all the piano concertante works and a double CD of his solo music (Capriccio C5387 review, C5463 review and C5332).

She opens with Dohnányi’s suave arrangement of the valse lente from Delibes Coppelia and I have to say does it full justice with technical aplomb and plenty of time to breathe; this is mainly why this takes seven minutes or so to Dohnányi’s four and a half – pretty much the maximum length of a 78rpm side (APR recordings APR7038). I must mention a miraculous live version by the great Mieczysław Munz, full of jeu perle but very fast – around four minutes! (Americus AMR20021022). Gülbadamova is certainly no slowcoach and the responsive and full bloomed piano is fabulous for this repertoire. She follows it with the Pastorale based on the Hungarian Christmas Song mennyből az angyal – the angel from heaven came to you – a work that Dohnányi programmed in recitals to the end of his life. Written around the time that Hungary lost much of its territory and Dohnányi’s home town of Pozsony became the Slovakian city of Bratislava it must have had great emotional attachment for him. The carol is set in lilting 6/8, its measures set in that very tonal but wide ranging harmony that Dohnányi was so fond of and is contrasted with a more turbulent central section after which the theme is played in an almost carillon style before the lilting refrain reappears. Three years previously Dohnányi had chosen another Hungarian folksong for his set of Variations on a Hungarian Folksong, Te túl rózsám a Málnás erdején – you are away, on the other side my darling – which had also been set by his friend Zoltán Kodály in a radically different manner in his Transylvanian Spinning Room. Some of the writing is similar to that in his Ruralia Hungarica, another work that was influenced by the folksong collecting of his colleagues Bartók and Kodály though he used the Transylvanian folk music in a much more romantic manor. The variations are clearly based in an E major/minor modality but Dohnányi is far reaching in his harmony and always emphasises the modal feel of the theme. Technically they are very much based on Dohnányi’s flamboyant, improvisatory playing and are imaginative and colourful, really deserving of a bigger audience; I would highlight the tranquil chordal variation five and the left hand octave variation that develops into the next two variations and gives the theme some rigour, so different from the almost bar-less nature of the original. The work closes with the most romantic, nocturnal variation, a hushed and atmospheric ending in which the harmonisation of the them slowly descends semitone by semitone to its major key end, consolation after the melancholy of the opening.

Dohnányi was one of many late romantic composers to try his hand at baroque forms as his Gavotte and Musette and Pavane from the 17th Century from his Humoresques op.17 testify. His Suite in the Olden Style is his most substantial tribute to the age but though the movements and style are baroque influenced – prélude, allemande, courante, sarabande, minuet and gigue – the writing is of course full bloodied and virtuosic. The opening prélude is an extended warm up fantasia in contrapuntal style and it sets the scene for the rest of the movements. I am particularly taken with the scherzo-like drive and vigour of the courante, thirds and octaves skipping across the keyboard, the rich sarabande and the elegant minuet.A hectic gigue, full of contrapuntal writing manages to explore as many side-steps of harmony as the previous movements. The form and titles may be olden style but the range and athletic virtuosity was very contemporary and at this distance of time we can see that Dohnányi’s approach to late romantic chromaticism was individual and successful.

The spirit of Brahms hovers over the first of the three pieces op.23, Aria. Dohnányi had largely escaped the heavy influence of Brahms that is so clear in his earlier works and while the cross-rhythms in the writing here still look like Brahms on paper the melody and and almost cinematic feel in the climactic sections are all Dohnányi. His love of dance, specifically the waltz, and his humour shine through in the valse-impromptu and the scurrying figuration of the capriccio. It is to the waltz that Gülbadamova returns to close this recital, playing the familiar transcription of Strauss’s evergreen treasure waltz.

It is interesting to hear these works played on Dohnányi’s own piano, its bold sound rich and captured remarkably well. For me it doesn’t add anything that Gülbadamova’s wonderful pianism doesn’t already say and I would have liked the booklet notes to include something from the pianist about how it felt to play this unusual instrument. It certainly looks good and I’ll admit that I wouldn’t mind trying out the piano myself but a cautionary note – Dohnányi loved the design but gave up playing it in concert after it failed to turn up one evening and he had to adapt back to a regular keyboard. Innovation is fine as long as it is widespread enough to be useful and practical.

There is at least one transcription, a concert version of the Brahms waltzes, that hasn’t made it into previous otherwise comprehensive releases and with a good couple of CDs worth of solo music left unrecorded by Gülbadamova I hope this release signals her intent to record the complete works.

Rob Challinor

Buying this recording via a link below generates revenue for MWI, which helps the site remain free.