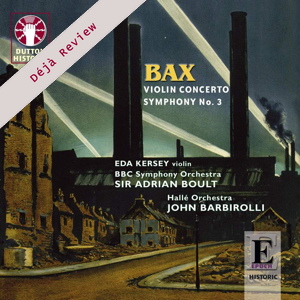

Déjà Review: this review was first published in August 2001 and the recording is still available.

Sir Arnold Bax (1883-1953)

Violin Concerto (1937-38)

Symphony No. 3 (1928-29)

Eda Kersey (violin)

BBC Symphony Orchestra/Sir Adrian Boult (concerto)

Hallé Orchestra/Sir John Barbirolli (symphony)

rec. 23 February 1944, Bedford Corn Exchange, UK (concerto); 31 December 1943, 12 January 1944, Houldsworth Hall, Manchester, UK (symphony)

Dutton Epoch CDLX7111 [73]

In one fell swoop Dutton restore the classic Barbirolli version of Bax 3 to the catalogue and usher in the first commercial release of Eda Kersey’s traversal of the Violin Concerto. Both are leading documents of their time and have much to tell us about Bax and performance practice.

The Concerto was written for Heifetz but disdained by him because, as Lewis Foreman tells us in his habitually exemplary liner notes, the work was insufficiently challenging. Truth to tell it is an enigmatic work if your reference points are the symphonies. It makes more sense if you group it with things like Maytime in Sussex and the overture Work in Progress. Even then it does not quite fit because this is a work with some fire in its veins. The composer likened its style to Raff but for me it is a dashing and poetic blend of Russian romance (vintage Tchaikovsky and Rimsky in Sheherazade mode – try 09.03 in the first movement) and Straussian panache of a type Bax also used in the Overture to a Picaresque Comedy.

There is only one other recording – a perfectly good and enjoyable version on Chandos. Lydia Mordkovich (the Chandos soloist and a most welcome and imaginative regular on that label) does not imbue the work with quite the ferocity which Eda Kersey finds. The last time I heard anything approaching this was Dennis Simons version, impetuous and poetic, broadcast by BBC Radio 3 circa 1979 in which the BBC Northern Symphony were conducted by that very fine Baxian, Raymond Leppard (still Indianapolis-based?). Now that is one broadcast that cries out for commercial release. Ferocity in Bax can be glimpsed in many of the older school conductors’ efforts as in the case of Stanford Robinson’s Bax 5 and Eugene Goossens’ Bax 2 – both BBC tapes from the 1950s and early 1960s. Goossens’ devastatingly gripping Tintagel with the New SO on 1930s 78s is also an object lesson in what Bax scores can gain from keeping things moving forward.

Kersey was to die in 1944 at the age of only 40. How sad a loss! It would have been wonderful if her version of the Arthur Benjamin Romantic Fantasy premiere had been similarly recorded by the BBC. The Fantasy was dedicated to Bax and the two corresponded regularly.

The recording of the concerto is in muscular mono prone to only one blemish: when the orchestra rises above ff on emphatic music the treble stratum succumbs to a shredded or shattery quality likely to be noticeable only if listening on headphones. Otherwise the audio image is stable and without fault though unsubtle by comparison with the Symphony’s commercial recording.

The Barbirolli Bax 3 is likely to be an old friend to many Baxians. First issued in 1944 under the auspices of the British Council it was finally issued on LP by EMI in the 1980s. In the 1990s it reappeared (though with a very short lease) in 1992 on EMI CDH 7 63910 2 (ADD) on the Great Recordings of the Century series. When the original 78s had been deleted their place was been filled (after a fashion and after years of silence) by Edward Downes’ LSO recording on an RCA LP later reissued on the Gold Label series in circa 1977 (the year of the Silver Jubilee in the UK).

For this Baxian, the Third Symphony counts as one of the most static of the seven – a natural partner to the Seventh. Its rhapsodic Russophile sympathies are much in evidence with hints throughout of Rimsky’s Antar and Russian Easter Festival and of Stravinsky’s Firebird. I would tend to bracket it with his own Spring Fire, Bantock’s Pagan Symphony and Vaughan Williams’ Pastoral rather than with the dynamic turbulent front-runners of the 1930s such as the Moeran, Walton 1, VW4 and his own 5 and 6.

Barbirolli invests the Symphony with great feeling – molto passione. Every detail is attended to with great and amorous care. Has the anvil blow at the crown of the first movement resounded as satisfyingly in any other recording – I think not?

The dedicatee of the Symphony (Sir Henry Wood) can be heard in a tantalising fragment of a Queen’s Hall rehearsal of the Third on a Symposium CD. His illness since the late 1930s (he was to die during the Summer of 1944) robbed us of a Wood-conducted Bax 3. It would not at all surprise me to discover that EMI had approached Wood before Barbirolli who had, comparatively recently, returned to war-scarred Britain from his spell with the New York Philharmonic Symphony.

The symphony’s recording sessions were presided over by Walter Legge and the intrinsic sound captured is much better rendered on the Dutton than on the EMI. From this point of view Dutton Laboratories have done a better transfer and remastering job than Peter Bown and John Holland for EMI Classics almost a decade ago. Taking one example: the bed of 78 hiss and burble, faithfully present in the middle background in the EMI, has been lowered substantially. Miraculously cyclical disc rotation blemishes have been neatly elided. Compare from 08.00 to 09.00 in the first movement in the EMI as against the Dutton. There is evidence here that the Dutton is the most solicitous and beguiling transfer this recording has had. It makes you wonder what the next generation of processing a decade down the road will have achieved.

The Dutton is a de rigueur addition for all Baxians and an antidote to the sleepy sloppy school of Baxian interpretation.

Rob Barnett

Help us financially by purchasing from