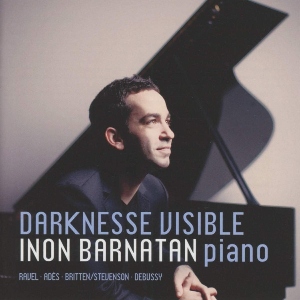

Darknesse Visible

Maurice Ravel (1875-1937)

Gaspard de la nuit (1908)

La Valse (1920)

Thomas Adès (b.1971)

Darknesse Visible (1992)

Claude Debussy (1862-1918)

Suite bergamasque (1905)

Ronald Stevenson (1928-2015)

Peter Grimes Fantasy on themes from Benjamin Britten’s opera for piano solo (1971)

Inon Barnatan (piano)

rec. 2010, The Performing Arts Center, SUNY Purchase, New York City

Reviewed as a download

Pentatone PTC5187235 [69]

Inon Barnatan has taken a typically imaginative approach to planning this recital. All of the music is inspired by poems or stories which touch on the interplay between darkness and light. Interesting, if wide, parameters, but it’s his mixture of familiar and less played pieces which make the disc so compelling.

We know that Ravel was fascinated by fiction which is centred on the fantastic, from the stories of Poe to the poetry of Aloysius Bertrand, whose collection Gaspard de la nuit has become famous for providing the inspiration for Ravel’s work for piano, after the pianist Ricardo Viñes had introduced it to the composer. Bertrand’s work made such an impression on Ravel that he prefaced each piece with its matching poem in the score. This simple decision proves highly illuminating in understanding the effects Ravel sought in each of the three pieces: immediately one has a sense of an aquatic kingdom from Bertrand’s careful use of flowing, liquid word sounds in his portrayal of the water nymph Ondine, the dread conjured by his flat, matter of fact description of the corpse of a hanged man caught by the setting sun in Le Gibet and the macabre in his choices of vocabulary in the portrayal of the gnome Scarbo, who seems to change size at will and whose body becomes blue before fading altogether like melting wax (‘son corps bleuissait’ Bertrand writes – you’ll go a long time before meeting that verb again in a similar poetic context).

Barnatan’s fine account emphasises the Lisztian qualities of the piece in its colouration and dramatic sense whilst making light of its technical challenges. In Ondine, he manages Ravel’s very tricky direction to Viñes that Ondine’s theme should not stand out but be very much part of the watery atmosphere, yet still be perceptible, and he achieves a wonderful effect of apparent suspension throughout, what another pianist, Steven Osborne, describes as Ravel’s subtle contravention of the laws of physics. Le Gibet is a perfectly judged tableau. The incessant bell here does not dominate the soundscape but is present as a nagging reminder of the limits of mortality, again the precise effect Ravel was seeking. In Scarbo we get a real sense of malevolence – Ravel very deliberately giving Bertrand’s poem a more sinister edge – and Barnatan never lets the fact that Ravel was consciously writing a difficult showcase of a piece intrude, we never feel the point of the piece is its virtuosic demands. One can also appreciate Barnatan’s subtle touches: for example, listen to how deftly he follows Ravel’s directions on pedalling and yet maintains absolute clarity.

In the first of two deeply interesting swerves, Gaspard is followed by a performance of Thomas Adès’s Darknesse Visible. Adès describes this piece in the score as an ‘explosion’ of John Dowland’s lute song In Darknesse Let Me Dwell, but its atmosphere is more reflective than violent and at times, rapt. Adès’s own recording from 2005 (Warner 0724356969957) is superb, other-worldly, with lovely layering of textures, but Barnatan on this recording is even subtler I think. In his hands Dowland’s theme becomes even more of a faint echo, a half remembered melody, which feels just right. As Barnatan points out in his booklet notes, Adès is also alluding to the lines Milton wrote describing the fires of hell: ‘Yet from those flames/No light, but rather darkness visible’ and his performance here is even more effective than the composer’s at bringing out those sepulchral qualities.

Verlaine’s poem Clair de lune was part of the inspiration for Debussy’s baroque infused Suite bergamasque. It’s the famous third movement of the Suite, refreshingly uncomplicated in Barnatan’s reading. He invests more complexity though in the surrounding works and the contrast works well. The potentially counterintuitive Tempo Rubato marking in the Prélude is played with beautifully shaped and even semiquavers but punctuated with rhetorical flourishes at the start which do have more flexibility. This is presumably what Debussy was after given he grumpily replied to Marguerite Long’s question about the tempo marking, ‘four semiquavers are four semiquavers’! Barnatan is very fine too in the minuet, where he voices Debussy’s changes of modes with absolute clarity. The Passepied which concludes is played with the lightest of touches and is absolutely a dance, even in its polyrhythmic passages.

From dancing Debussy to psychodrama in Suffolk next and a real rarity: Ronald Stevenson’s tremendous Fantasy on Peter Grimes. Like a lot of Stevenson’s piano music its difficulty can be a barrier for the would be performer but it’s an amazingly effective synthesis of a number of themes from the opera and a less than commonplace opportunity for pianists to play something Brittenesque. There are only a handful of recordings and Barnatan produces a highly compelling account that I’d want to hear again in preference to others in the catalogue. This includes Peter Jablonski’s recent version on Ondine (ODE 1453-2), which I find less agile. On this disc Barnatan has a strong sense of narrative and is alive at every point to Stevenson’s ingenious writing. Listen to the way Britten’s pizzicato is reproduced at the end of the work for a striking example of this.

Barnatan concludes with an evocative, even more than usually doom-laden account of the single piano version of Ravel’s La Valse. In his notes he reminds readers of the parallel some commentators have suggested between the piece and Poe’s Masque of the Red Death and it certainly sounds as if it was at the forefront of his mind in this performance. As he writes, ‘as the waltz spirals towards an ecstatic and maniacal end, the darkness is, plainly, visible.’ It’s undoubtedly an effective way to end even if I didn’t quite find the range of colours and instrumentation that Bertrand Chamayou brings in his magnificent recent Ravel inspired disc (Erato 2173260123) which Philip Harrison also admired (review).

I’ve very much enjoyed this themed recital. As with the best programmes, it’s not just the inspired unfamiliar choices in themselves which make it compelling, it’s the way they illuminate works we think we know. Barnatan‘s own booklet notes are unfussy and insightful and the sound is excellent. I was puzzled to see that the recording apparently took place over fifteen years ago. It turns out that it is a reissue of a disc first put out by Avie (AV2256) and reviewed here by Christopher Howell (review). I think it’s fair to say that our views of some of the performances and indeed pieces don’t always accord, but that’s part of what makes MusicWeb so interesting!

Dominic Hartley

Buying this recording via a link below generates revenue for MWI, which helps the site remain free