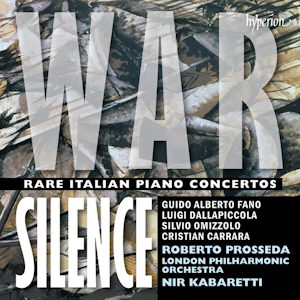

War Silence – Rare Italian Piano Concertos

Guido Alberto Fano (1875-1961)

Andante e Allegro con fuoco (1900)

Luigi Dallapiccola (1904-1975)

Piccolo Concerto per Muriel Couvreux (1939-1941)

Silvio Omizzolo (1905-1991)

Piano Concerto (1960)

Cristian Carrara (b. 1977)

War Silence for piano and orchestra (2015)

Roberto Prosseda (piano)

London Philharmonic Orchestra/Nir Kabaretti

rec. 2022, Henry Wood Hall, London

Hyperion CDA68458 [77]

As conductor Nir Kabaretti argues in a brief preface, Italy has exerted a huge influence upon the history and development of Western classical music, but its contribution to the piano concerto genre is much less obvious. This disc is the result of pianist Roberto Prosseda’s proposal: four little-known concertos. It seems a tad dubious in the first place to say that one nation or another might have a specific affinity with a particular instrumental genre. Happily, the selections admitted to this project – a somewhat unusual one for Hyperion – complement each other rather well. That may be because hints of Italianate lyricism pervade them all to a certain degree, despite the wide divergences in style and background.

The sequence is chronological. Guido Alberto Fano’s output has maintained a foothold in the catalogue thanks to Italian labels such as Tactus and Phoenix Classics. He was an older contemporary of Respighi. His thirteen-minute Andante e Allegro con fuoco exudes elegance and lyricism, but I found it stubbornly unmemorable. The work grows from a hymn-like idea imparted by brass and wind. The soloist enters in due course and plays along with this theme. It recurs rather uneventfully throughout the brief Andante, shaded by a discreet orchestral backcloth. This slow section yields without a pause to its faster, longer counterpart. The con fuoco designation implies more drama than actually transpires, although a mini-cadenza at 5:30 briefly glowers. Some of Fano’s progressions and escalations seem mildly Scriabinesque. Notwithstanding Prosseda’s refined tracery and the ardency of Kaberetti’s direction, the neglect of Fano’s rather awkward confection strikes me as unsurprising.

I am familiar with a good deal of Dallapiccola’s output. I have held a bit of a light for him ever since participating in my local choir’s surprisingly impassioned account of Due Cori di Michelangelo Buonarroti il Giovane almost half a century ago. So it is a source of no little shame that this is the first time I have encountered his delightful Piccolo Concerto per Muriel Couvreux, especially since it has been commercially recorded at least three times. (A crystalline reading by Bruno Canino, apparently still available on the Italian Nuova Era / Icarus label has been uploaded to YouTube.) In his otherwise comprehensive booklet note, Sandro Cappelletto only tells half the story behind the work’s provenance. Prior to the outbreak of World War II, the composer was working on a more serious piece, the anti-fascist cycle Canti di Prigionia. At the same time, he was hopeful of forging an opera upon Antoine de Saint-Exupéry’s then fashionable novella Night Flight (Volo di Notte); he sought the assistance of his friend Jacques Rouché, the director of the Paris Opera, in persuading the author’s publishers Gallimard to release the rights to the book. Rouché succeeded in this venture. By way of thanks, Dallapiccola dedicated this concerto to his seven-year-old grand-daughter Muriel Couvreux. The new work also provided something of a gentler distraction for the composer during the completion of the Canti.

The concerto is lightly scored, but it is inspired by the dream-like enchantment of childhood rather than designed to be played by a child. Its two movements each incorporate a tripartite structure. The first evolves from gentle pastoral lines conveyed by individual winds and strings, and single piano notes which land like raindrops. Atmospheric and impossibly attractive, the mood evokes the Ravelian atmosphere of Ma mère l’Oye, albeit shot through with a distintive Mediterranean flavour. A fanfare heralds a lively Girotondo central section, whose skittish piano writing and colourful percussion ultimately melt into a reflective episode for the soloist. This concluding part is marked Ripreso – its pentatonic hints enhance its mildly fantastical spirit.

Prosseda invokes great tolling bells in the opening bars of the second movement; his repeated figurations yield eventually to the muted, pastel strains of an extended central nocturne shaded by harp, woodwinds and muted brass. Prosseda traces a delicate commentary and contributes to the crepuscular mood. The confident opening of the mini finale alludes to the campanalogical gestures which opened the movement before its graceful neoclassical coda.

A twenty-minute concerto divided into six brief episodes can easily descend into diffuseness. This one is remarkably coherent and effortlessly elegant: no empty virtuosity here. Piccolo Concerto per Muriel Couvreux is atmospheric, adorable and surprisingly original. It is beautifully played and recorded here. For me, it constitutes the highlight of this album.

Silvio Omizzolo is a completely new name to me. If the 1960 Piano Concerto is typical of his output, it might be assumed that this slightly younger contemporary of Dallapiccola pursued a more conservative compositional path. The swaggering piano solo which launches the work projects the unmistakeable tang of Prokofiev. The orchestra continues the momentum generated by this material. It is confidently arranged, and the keyboard writing is impressively idiomatic, but I found Omizzolo’s music as a whole to be disappointingly pedestrian.

There is some effective brass writing toward the end of the first movement, whilst the angularity of the piano writing of the central Andante is vaguely Bartokian. There is no doubting Omizzolo’s methodological efficiency but his concerto is undermined by what I perceive to be a dearth of real individuality. Prosseda offers real commitment to the piece, but several pianistically challenging solo passages prove to meander along rather aimlessly, negating what little novelty I identified on first hearing. It is a similar story in the Allegro finale. Omizzolo’s superficially exciting motoric rhythms conceal rather uninspired melodic and harmonic matter. The cadenza preceding the coda is momentarily atmospheric, but the closing bars encapsulate a work I found somewhat humdrum.

Cristian Carrara, now in his late forties, is clearly a figure with a growing reputation, as demonstrated by a recent enthusiastically received Naxos portrait, also conducted by Nir Kabaretti (review). Like the four works on that album, his entertaining and intermittently moving piano concerto War Silence attempts to convey something of a narrative. Whilst I am not entirely sold on the link between the concept and the sounds themselves, Carrara’s concerto is colourful and impressively crafted. According to the interview with the composer reproduced in the booklet, the titles of the three linked panels, Trenches, Solitudes and Fruts seem to allude to the internal states of those involved directly in conflicts (as participants, witnesses, victims or survivors) rather than describing literal situations or consequences. For my part, this understanding had little or no effect on my genuine enjoyment of War Silence.

The orchestral introduction of Trenches is eerily reminiscent of Alexander Mosolov’s constructivist hit Zavod (Iron Foundry) – whether this is a conscious reflection or not, Carrara runs enthusiastically with these propulsive rhythms in a movement which pushes on with variety, colour and memorability. Certain influences have been drawn from the entire post-1945 orchestral spectrum, but to his great credit Carrara has fused them into a coherent whole which sounds fresh and powerful. The central Solitudes addresses the inner silences experienced by participants stuck in the trenches and their fragile aspirations of relative normality. Here Carrara’s music is cinematic and emotional, but not remotely schmaltzy. He clearly has a real flair for orchestration, and his solo piano writing is subtle and telling. The toccata-like finale Fruts is exciting and optimistic; the momentum generated by the stabbing orchestral material will certainly appeal to those who enjoy the music of John Adams. The veteran American seems an obvious reference but the style has been fully absorbed and personalised by Carrara.

Does the disc hang together as a programme? The ‘rare Italian’ theme is possibly a bit contrived, because in stylistic terms the four concertos could not be more different. I suspect the response of many listeners will be similar to mine. They will enjoy a couple of the pieces and be less convinced by the rest. But those of us who are suckers for fresh repertoire will certainly find something to like. With excellent performances and first-rate Hyperion sonics, this novel, generously filled disc can in the final analysis be regarded as a pretty safe investment.

Richard Hanlon

Buying this recording via a link below generates revenue for MWI, which helps the site remain free