Giacomo Puccini (1858-1924)

La bohème (1888)

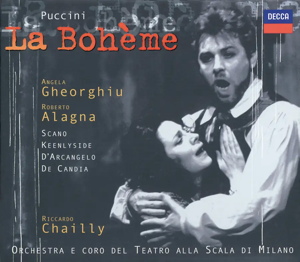

Rodolfo: Roberto Alagna (tenor)

Mimì: Angela Gheorghiu (soprano)

Marcello: Simon Keenlyside (baritone)

Musetta: Elisabetta Scano (soprano)

Coro di voci bianche del Teatro alla Scala e del Conservatorio “G. Verdi” di Milano

Coro & Orchestra del Teatro alla Scala/Riccardo Chailly

rec. 1998, Teatro Studio, Piccolo Studio, Milan

Decca 4660702 [2 CDs: 100]

Rodolfo: Roberto Alagna (tenor)

Mimì: Leontina Vaduva (soprano)

Marcello: Thomas Hampson (baritone)

Musetta: Ruth Ann Swenson (soprano)

London Voices & London Oratory Boys’ Choir

Philharmonia Orchestra/Antonio Pappano

rec. 1995

Warner Classics 3586502 [2 CDs: 101]

Back at the turn of the century, Ian Lace included these two recordings in a mini-survey of five major recordings of La bohème; otherwise, they have not been reviewed here on MusicWeb. A recent BBC Radio 3 Record Review duly acknowledged Karajan’s famous recording – recently re-issued in a new remastering by Decca – as luscious but considered it too “monumental” for everyday listening and while the vivacity and strong character of Beecham’s equally celebrated version were duly acknowledged, both were usurped by a first choice of the Pappano recording above. I disagree, which is why I included both of those in my list of “Untouchable” recordings – and it seems that my colleagues John Quinn and the aforementioned IL tend to agree with me. Nonetheless, I thought it might be instructive to consider the Pappano and Chailly pair comparatively, as they were made within three years of each other as the 20C drew to a close and both starred a youthful Roberto Alagna in the lead tenor role. In that regard, those two recordings are something of a throwback to the rivalry of the 50s between Decca and EMI, whereby each would almost simultaneously issue sets of core operatic repertoire featuring their respective house stars.

Neither of my sets provides a physical libretto but I have the 2006 EMI Classics issue in a cardboard box and the Decca double from 2012 which directs you to a website for the text and translation; however, the original Decca issue provided a booklet with libretto. Of course the EMI recording has since been re-issued, in 2018, under the Warner label.

To the comparison: I first played both recordings from the rumbustious opening, up to “Abbasso, abbasso l’autor!” and one immediately registers the cloudy throatiness of Hampson’s baritone compared with the depth and resonance of the young Keenlyside; secondly, Decca’s sound is preferable: fuller, more spacious; thirdly, Alagna sounds more energised and engaged; fourthly, I find Chailly’s conducting to be more nuanced and varied than Pappano’s and, finally, Samuel Ramey as Colline does not sound to be in best voice compared with the younger Ildebrando D’Arcangelo. To test this, I heretically charged forward towards the end of the opera in both recordings to sample the basses’ “Vecchia zimarra” and D’Arcangelo proved to be in much cleaner, richer voice than the uncharacteristically woolly Ramey – an artist I normally absolutely revere – though neither, I might add, is a patch on Karajan’s Ghiaurov. In other words, my first impressions confirmed a clean sweep in every respect for Chailly over Pappano.

Returning to proper, chronological listening, the pendulum begins to swing back in Pappano’s favour, as Chailly’s Schaunard, Roberto De Candia is weakly voiced and acted compared with Pappano’s – he being no less than Keenlyside again, singing Schaunard before he was “promoted” to Marcello. On the other hand, I find Alfredo Mariotti’s Benoit more amusing and less hammy than Enrico Fissore’s. The teamwork in the quickfire exchanges between the band of young men in both recordings is excellent.

To the two principal singers: Leontina Vaduva almost underplays Mimì, in that she chooses to stress her sweetness and vulnerability at the expense of vocal effulgence, and there is no doubt, fine as she is, that her compatriot Angela Gheorghiu has the more individually beautiful voice; she rivals Freni and de los Ángeles for pathos and vocal opulence- and I love the way she carries through the line from “in cielo” to “ma, quando vien lo sgelo”, all on one breath. Vaduva is less the “grande dame”, however, and some may find her innocence more dramatically convincing; she quite often sounds like a third great Romanian soprano, Ileana Cotrubas, whose gift was for pathos. Her “Si. Mi chiamano Mimì” is enchanting and she can find reserves of power for “Il primo sole”. I recently reviewed Carlo Rizzi’s Rigoletto and found the same qualities in her Gilda; she remains, I think, an undervalued artist.

Alagna is fine in both, if marginally fresher and sweeter for Pappano, but how I miss the gleam and brilliance of Pavarotti and Björling. Both have a roguish, masculine elan which evades Alagna, with his grainier sound, for all that his singing is boyish and impassioned. He nonetheless charms, and convinces as a lover, frequently singing tenderly. Does the Decca engineering artificially enhance the resonance of his top C? Possibly, but it sounds great.

Pappano finds marginally more sweep, swoon and Schwung for “O soave fanciulla”; Chailly dawdles a bit too much over phrases. In both recordings, the lovers sound the last note on “Amor!” with the tenor taking the harmonic G to the soprano’s floated top C instead of joining her, which purists prefer and which better reflects their new-found compatibility, rather than offering an opportunity for vocal display. Gheorghiu’s top C is the more ethereally sustained.

All of which leaves me wholly undecided between the two recordings by only the end of Act 1, with three more to go – and the riotous Parisian street scene opening the second Act is crucial to establishing the right joie de vivre, as a contrast to the ensuing tragedy. Both conductors succeed – but it is here in particular that Alagna, Gheorghiu and Pappano recapturing the swaggering mood of their contemporaneous recording of La rondine and have a Musetta in the pert, pure and prettily-voiced Ruth Ann Swenson, much superior to Elisabetta Scano, who has a strange, bottled, monochromatic timbre with occluded vowels. Swenson ensures that Act II swings in Pappano’s favour.

On to Act III. The frosty, chilly introductory music sets an atmosphere completely different from the preceding act; both accounts are good but I find Chailly’s delicate touch and the rounded acoustic of the Decca recording to be slightly more appealing. In both recordings, the milkmaids, Musetta’s voice offstage and the pizzicato plunks are sensitively distanced. Alagna is a little rawer of tone for Chailly but also more emotionally varied and demonstrative. The duet between Marcello and Musetta outside the inn is gloriously sung by Gheorghiu and Keenlyside, too; at first, Hampson and Vaduva pale by comparison as they cannot plumb the emotional depths of that desperate exchange but Vaduva in particular unleashes her voice most effectively at climactic moments while Gheorghiu is even more moving in “Donde lieta usci”.

And so it comes down to the last act, with its bitter-sweet admixture of the comical and the heart-rendingly sad, beginning with the immortal duet “O Mimì, tu più non torni” – and here it is the Alagna-Keenlyside pairing which prevails, as Hampson croons and Chailly finds more passion in the music, first pushing the tempo along a little more than relaxing for the soaring outpouring of nostalgic longing from the lovelorn friends. Gheorghiu is searing in her death scene but Pappano and the Philharmonia are at their subtle best here and Vaduva digs deep to tug at our heart strings; there is little in it.

Ultimately the balance sheet for each respective recording presents a confused and confusing picture. Both are beautifully played by fine orchestras and expertly conducted by flexible, sympathetic conductors. Alagna’s performances are barely distinguishable one from the other; Gheorghiu is richer voiced but Vaduva is so touching. Decca have a relatively weak Musetta and Schaunard but their Marcello and Colline are better – and Decca’s sound is more immediate. Neither recording, fine though both are, usurps my attachment to Karajan’s great achievement with its stellar cast, yet both offer a deeply satisfying account of a miraculously wrought score. Forgive me if I cannot offer a definitive preference – but as primarily “a canary fancier”, for the big moments in this opera I cannot dispense with the opulence of principal voices like those of Gheorghiu and Keenlyside, so I am inclined towards Decca as the better of the two by a whisker. It was ignored by Record Review probably because its format hardly allows for comprehensiveness – but it surely merited a mention.

Ralph Moore

Buying these recordings via the links below generates revenue for MWI, which helps the site remain free.

(Decca)

(Decca)

(Warner Classics)

(Warner Classics)

Other cast

Warner:

Schaunard: Simon Keenlyside (baritone)

Colline: Samuel Ramey (bass)

Benoit/Alcindoro – Enrico Fissore (bass-baritone)

Parpignol – Philip Sheffield (tenor)

Sergente dei doganieri – Jeffrey Carl (baritone)

Un doganiere – Paul Parfitt (bass)

Decca:

Schaunard: Roberto de Candia (baritone)

Colline: Ildebrando D’Arcangelo (bass)

Benoit/Alcindoro – Alfredo Mariotti (bass)

Parpignol – Alberto Ragona (tenor)

Sergente dei doganieri – Gianfranco Valentini (bass)

Un doganiere – Franco Podda (bass)