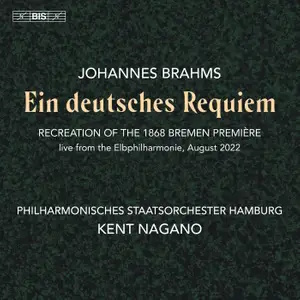

Johannes Brahms (1833-1897)

Ein Deutsches Requiem (1868) – Recreation of the 1868 Bremen Premiere

Kate Lindsey (mezzo), Jóhann Kristinsson (baritone)

Veronika Eberle (violin), Thomas Cornelius (organ)

Philharmonisches Staatsorchester Hamburg/Kent Nagano

rec. 2022, Elbphilharmonie, Hamburg

Texts and translations included

BIS BIS-2720 SACD [2 discs: 93]

Brahms was born and bred in Hamburg. His father, a musician even played for a time in the orchestra which now presents Ein Deutsches Requiem in its original, six-movement version. By 1865, when Brahms, aged just 32, started to compose the work, he had concentrated his energies, with one notable exception, on songs, piano pieces and chamber music. These included some real treasures but many awaited a successor to the mighty Piano Concerto No. 1 which had been finished in 1858 and premiered the following year when the composer was only 25.

February of 1865 had seen the death of Brahms’ beloved mother Christiane. Personally, I feel this bereavement had more of a bearing in the composer’s creation of the work than the sad loss of his friend and mentor Schumann nine years earlier. The work’s first three choral movements were premiered in Vienna in December 1867 and by the following year Brahms was ready to present the work in Bremen with six movements completed.

In this presentation from BIS, the Hamburg Philharmonic State Orchestra and massed local choirs numbering well over 400 recreate the actual premiere of Ein Deutsches Requiem in Bremen Cathedral on Good Friday 1865. There is a strong choral tradition and rich heritage in North Germany and the many groups of voices assembled here nicely mirror what Brahms would have had under his baton on that day back in 1865. Those times were different, however, and the concert also included a ten-minute instrumental interlude halfway between the six movements (led by violinist Joseph Joachim), and a finale consisting of Bach’s “Erbarme dich” from the St. Matthew Passion and sundry selections from Handel’s Messiah, including (surely inappropriately for Good Friday) the Hallelujah Chorus.

Brahms’ German Requiem is his largest composition in terms of length and scale. The piece is based on texts assembled by the composer himself from his own German Luther Bible. It is not a liturgical work in any sense; rather, it is concerned with comforting sorrowful mourners who are bereaved. There is no direct reference to Christ in the work and in only one movement does the text even mention death; in fact, the most common word in the work is Freude (Joy). North Germany was (and still is) predominantly Protestant. At the time of the premiere, the clergy at Bremen were uneasy at the lack of references to the crucifixion and the resurrection of Jesus on this of all days, which perhaps explains the items added at the end of the concert.

Kent Nagano’s recreation of the premiere happened at the huge Elbphilharmonie. Its Grand Hall is oval shaped with seating all around the stage. The acoustics are clear and spacious. I imagine the reverberation time is significantly smaller than the Cathedral in Bremen, nonetheless. The BIS recording does give the listener a sense of the huge numbers in the choir and the imposing scale of the performance but as you will read, it is not wholly successful in terms of balance.

In “Selig sind, die da Leid tragen”, Nagano adopts a moderate pace. This movement is dark and sombre. Brahms drops the violins to intensify the doleful heaviness in the writing. In Gardner’s recent recording from Bergen on Chandos (review) I love the entry into the piece and the sense of awakening Gardner brings in that first minute before the choir enter. I don’t hear that same sense of preparation here. Nagano takes 9:48 in this first movement but feels much slower. Gardner in Bergen takes 10:41 and Daniel Harding in his superb 2018 recording with Swedish forces for Harmonia Mundi (review) takes a long 11:24.

The dark and sombre timpani triplets that underscore “Denn alles Fleisch, es ist wie Gras” accompany a march rhythm that Nagano paces perfectly. The choir is huge but when singing softly (which is harder to do than you might think) is very moving. In the middle section where they sing “Be patient”, they sound serene, even angelic. Unfortunately, some of the lovely countermelodies Brahms writes here go for little when pitted against the huge vocal forces. Chandos’ sound stage created by the wonderful Pidgeon/Couzens partnership allows Gardner’s magic with the Norwegian instrumentalists to shine through. Harding, working with a small professional crack choir, is very different to this new version. He also favours a period-instrument style approach (although the period cannot have been Bremen circa 1865 judging from what we are hearing in this recreation).

“Herr, lehre doch mich” is led by the young Icelandic baritone Jóhann Kristinsson. He has a virile warm tone which we hear naturally and un-boosted. Nagano nicely handles his forces in this tricky movement. The impressive fugue beginning at 07:00 shows Brahms’ mastery of counterpoint at it best. He worshipped at the altar of Bach and Schütz and here proves to be a worthy disciple. I think this is Nagano’s finest movement in the work harnessing his vast forces most effectively.

At this juncture we have our instrumental break. Veronika Eberle on violin entertains, accompanied by Thomas Cornelius on organ. I find the eleven minutes baffling to be honest. Interpretively the three miniatures are fine, I just don’t get why they are there. Perhaps Brahms and the committee putting on the concert felt they needed to offer a spotlight to Joachim who was leading the violin section?

Ein Deutsches Requiem continues with the calm lyricism of “Wie lieblich sind deine Wohnungen”. This is by far the shortest movement in the Requiem. There is a sense that the sound is a little swamped as the singing line is very much in the middle of the voice. Nagano paces nicely again though and his strings sing beautifully.

“Denn wir haben hier” contains a baritone-led scene where we hear the interpolated Tuba Mirum and Mors stupebit of the Latin Dies Irae sequence. Brahms does not dwell on these things, though, relishing instead the triumph over death which Christ has won for all mankind with maximum affirmation. I read somewhere it could be called a luminous solemnity. “Death, where is your sting? Where? Where?” He seems to taunt. In his solo work here, I felt Jóhann Kristinsson lacked a bit of weight and sonority in his lower register but gave a decent effort. The chorus seem to be enjoying themselves and are in great voice. The recording, like some super versions of Mahler 8 I could name, however, does struggle to maintain contrast in the forte of densely orchestrated sections of this great movement. Listening comparatively to my other versions in this section, Edward Gardner in Bergen is masterful with sharp and pointed accents. Daniel Harding’s sleek account must also not be overlooked when considering a modern up-to-date recording of the Requiem.

“Selig sind” begin the sopranos in the last movement, in symmetry with the very opening of the Requiem. The ethereal high voices are joined by basses in this most consoling passage from the Book of Revelation. Unlike in the first movement, Brahms brightens things with violins and a mastery of harmony and orchestration. The performance of this last movement is very well done. The musicians of the Hamburg Philharmonic State Orchestra and their surrounding choirs should be very proud of their collaboration in the service of the work. People who I know have sung the work tell me that it is a most rewarding work to sing and I imagine being part of this experience will stay with these singers for a lifetime.

As stated, the epilogue to this recreative concert is a twenty-minute sequence of Bach and Handel. American mezzo Kate Lindsey is the soloist – and very good she is too. She sings around the world and in the last couple of years has taken on Sesto, Rosina, Despina and the Composer (Ariadne auf Naxos) in Vienna and Octavian at La Scala. Her voice is clear and has a woody resonance in the middle. Her top notes are sweet and unforced and what’s more she has a trill which is handy in the Handel work. I didn’t expect much from this encore to Ein Deutsches Requiem but was pleasantly surprised.

As far as I can make out, Brahms made no textural changes to the score from the 1868 Bremen Requiem to its eventual fully complete first showing the following year in Leipzig – just the addition of the soprano-led “Ihr habt nun Traurigkeit”. The liner notes provided by BIS are of the highest quality and lay out interesting facts about the Bremen event as well as providing biographical detail on all the performers and ensembles. I cannot, however, recommend this as a library choice for the work due to the sonic issues I have laid out. If you are looking for an ultra-modern account both the Gardner and Harding records are complementary and wonderful, in my opinion. I will nonetheless lavish praise on the good burghers of Hamburg for their enterprise in bringing this project to fruition. I read that in the Spring of 2025 Nagano will recreate the performance with his old orchestra in Montreal.

Back in 1865 when Brahms started composing the work the musical world was rocked by the first performances of Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde. Three years later and only a couple of months after the Bremen premiere, another German city staged the first Die Meistersinger. Many in the establishment took sides: the traditional Brahms on one side looking back and building on from German heritage, the maverick Wagner on the other opening new sound worlds and concepts in music drama. The wise Hans Sachs however, who knew a thing or two about music and resolving differences, puts it best: “Verachtet mir die Meister nicht, und ehrt mir ihre Kunst!” (Scorn not the Masters, I bid you, and honour their art!). Brahms did just that, and so do everyone involved here. My respect to them.

Philip Harrison

Buying this recording via a link below generates revenue for MWI, which helps the site remain free

Other works performed in the 1868 premiere and on this disc

Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750)

Andante from Violin Concerto in A minor, BWV 1041 Version for violin and organ by Thomas Cornelius

Giuseppe Tartini (1692-1770)

Andante from Violin Concerto in B flat major, D 120 Version for violin and organ by Thomas Cornelius

Robert Schumann (1810-1856)

Abendlied No. 12 of ‘Zwölf Klavierstücke für kleine und grosse Kinder’, Op. 85 Version for violin and organ by Joseph Joachim (violin) and Thomas Cornelius (organ)

Johann Sebastian Bach

“Erbarme dich” from the St Matthew Passion, BWV 244

Georg Friederich Handel (1685-1759)

from Der Messias, in the arrangement by W. A. Mozart, K 572

“Kommt her und seht das Lamm”

“Ich weiß, dass mein Erlöser lebet”

“Halleluja”

Choirs

Chor der KlangVerwaltung

Cappella Vocale Blankenese

Chor der Kantorei St. Nikolai

Compagnia Vocale Hamburg

Franz-Schubert-Chor Hamburg

Hamburger Bachchor St. Petri

Jugendkantorei Volksdorf

Kammerchor Cantico

Vokalensemble conSonanz

Choral direction: Jörn Hinnerk Andresen