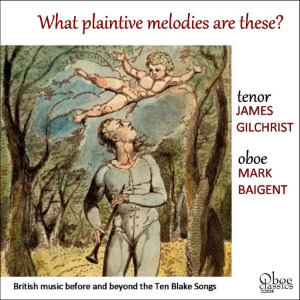

What plaintive melodies are these?

James Gilchrist (tenor)

Mark Baigent (oboe, cor anglais)

Mira Marton (violin), Joanna Patrick (viola), George Ross (cello), Fiona Mitchell (clarinet)

rec. 2024, St Martin’s Church, East Woodhay, UK

Texts and full notes downloadable via the website

Oboe Classics CC2038 [61]

The combination of voice and oboe in the British repertoire didn’t originate with Vaughan Williams’ Ten Blake Songs of 1957. In fact, it goes back at least to Philip Napier Miles’ Four Songs of 1925, though Cyril Scott had written his Idyllic Fantasy for voice, oboe and cello in 1921. Happily, they’re all included in this cleverly programmed recital, which has many a twist and turn to entertain the curious listener.

The Ten Blake Songs are divided into two sets of five and set as two blocks here, beginning and ending the disc and programmed in the order in which they were submitted for the 1958 film The Vision of William Blake. Potent as ever, they’re performed by James Gilchrist and Mark Baigent with refinement and elegance. Though he was pushing 60 when he recorded this recital in August 2024, and though his vibrato has loosened and the voice is inevitably no longer in its bloom, Gilchrist has lost nothing in his ability to arc across a phrase with unerring aptness. For a performance that radiates a sense of authenticity, you’d need Ian Partridge and Janet Craxton as she gave the premiere with Wilfred Brown. Their cited disc conjoins VW’s song with those of Peter Warlock, whose desolate and desolating The Curlew haunts a number of the pieces in this release, including, indeed, the Vaughan Williams.

Cyril Scott’s song, which is all but unknown, is set to his own poem and is a largely melancholy eclogue in which the oboe’s lyricism is amplified by the muted cello until things get incrementally friskier. By one of those coincidences, Herbert Murrill’s songs have recently been released on First Hand Records FHR161 and include his early and rather lovely Three Carols, composed in 1929 whilst he was still an organ scholar at Worcester College, Oxford. The last, The Falcon, the Corpus Christi Carol, is sung by Gilchrist in such a way that he seems to come towards the microphone and then walk away from, the better to coney the falcon’s flight. In St Martin’s Church, East Woodhay this works evocatively.

The central place in the recital is taken by Carey Blyton, whose Lyrics from the Chinese is sheer delight. It’s cast for tenor, oboe and string trio and was composed in 1953-4 but later expanded in 1957-8 for high voice and string orchestra, adding a poem and three string interludes. The expanded later version has been recorded but no one at Oboe Classics is aware of a recording of the original. It ranges stylishly over lissom, refined romanticism and extrovert wit, and takes in more briefly troubled Curlew-like moments in the third song, where the voice is pushed very high – possibly the reason Blyton recast it for high voice. The vocal line is attractive, the oboe writing is lovely and whilst Gilchrist, Baigent and their string colleagues are generally slower than Ian Partridge in the orchestral version, they are especially winning in the last song of the set with a string cushion supporting lonesome lyricism and hints, once again, of Warlock.

Rutland Boughton’s unpublished Fairy-Led is another neglected song written for voice, oboe and clarinet – a witty and very brief setting. There’s also Kind Ghosts from Britten’s Nocturne, probably the best-known piece here and finely balanced. Baigent plays the cor anglais. Which leaves just Philip Napier Miles, whose Four Songs, to poems by Robert Bridges will be new to most listeners. They’re actually written for baritone but make a fruitfully contrastive set for Gilchrist, from the fanfare-like oboe introduction to The Cliff Top, through the forlorn seascape of Thou art alone, fond lover to the antique folklore of the final song, When June is come.

If you anticipated a voice-and-oboe programme would bring forth a multitude of ascetic melancholia, think again. The recital is, instead, bathed in warmth and sunshine though there are flecks of sadness to balance things, quite properly. The recording has been sympathetically judged in the church acoustic of St Martin’s. If you want the full programme notes and the songs they are available from the label’s website – not ideal but cost-cutting, and fortunately Gilchrist’s diction is clear.

Everything here is a premiere recording in these formats, another drawing point.

Jonathan Woolf

Buying this recording via a link below generates revenue for MWI, which helps the site remain free

Contents

Ralph Vaughan Willams (1872-1958)

Ten Blake Songs (1957)

Cyril Scott (1879-1970)

Idyllic Fantasy (1921)

Herbert Murrill (1909-1952)

Three Carols (1929)

Carey Blyton (1932-2002)

Lyrics from the Chinese, Op. 16a (1954)

Rutland Boughton (1878-1960)

Fairy-Led for Voice, Oboe and Clarinet (1940): Poem, Fairy-led

Philip Napier Miles (1865-1935)

Four Songs, Op. 17 (1925)

Benjamin Britten (1913-1976)

Nocturne Op. 60 (1958), excerpt, Kind Ghost