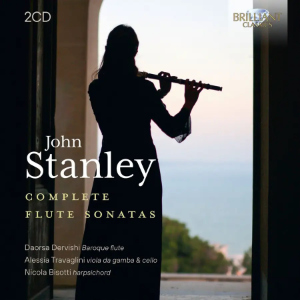

John Stanley (1712-1786)

Complete Flute Sonatas

Eight solos for flute and basso continuo, Op 1 (1740)

Six solos for flute and basso continuo, Op 4 (1745)

Daorsa Dervishi (baroque flute), Alessia Travaglini (viola da gamba/cello), Nicola Bisotti (harpsichord)

rec. 2021, Basilica di San Giovanni in Canale, Piacenza

Brilliant Classics 96397 [2 CDs: 138]

John Stanley is one of those English composers of the mid-18th century who receive relatively little attention due to the importance of George Frideric Handel. He is mainly known for his organ voluntaries and two collections of concertos: the Op 2, a set of six concertos for strings and basso continuo, and the organ concertos Op 10.

At the age of two, he became blind due to an accident at home. At the age of seven, he started studying music, and only five years later he was appointed organist at the church of All Hallows Bread Street, near St Paul’s Cathedral, where his teacher, Maurice Green, was the organist. In 1726, he moved to St Andrew’s, Holborn, and in 1734 he was made organist to the Honourable Society of the Inner Temple. The popularity of his voluntaries among today’s organists is not a new phenomenon; his playing attracted many colleagues, among them Handel. Stanley was also an excellent violinist, and in 1729 he became the youngest person to gain a BMus degree from Oxford University.

Not only did Handel show his interest in Stanley’s playing, Stanley in turn was an admirer of Handel’s music. In the 1750s, he directed performances of Handel’s oratorios, and after Handel’s death he took responsibility for the Lenten oratorio performances at Covent Garden, and later at Drury Lane. He himself composed some oratorios which were strongly inspired by Handel’s. In 1770 he became director of the Foundling Hospital, where from 1775 to 1777 he directed performances of Messiah.

A look at his work list in New Grove is somewhat depressing, as a substantial part of his oeuvre has been lost. Among the lost works are his court odes – all fifteen of them. Also lost are incidental music and a masque. However, there is still much to be explored, and it is hard to understand that so much of his output is ignored, such as about ten anthems, several hymns and several collections of secular cantatas.

Among the neglected works are also the two sets of sonatas for transverse flute and basso continuo that are the subject of the production under review here. As far as I have been able to check, not a single sonata from Opp 1 and 4 has been recorded before. From that perspective, this recording is ground-breaking, especially if we consider the quality of these sonatas.

The Op. 1 was published in 1740 and includes eight sonatas. The title page says Eight Solos for a German Flute, Violin or Harpsichord. This indication was mainly driven by commercial motives. Nicola Bisotti, in his liner notes, states: “Despite this editorial decision the musical markings seem to indicate flautist technique while the precise numerical marking of the figured bass would lead to a distinct lack of the sustained harmony in the music suggested by Stanley, were the music performed by the harpsichord unaccompanied.” The mention of the violin may also indicate that at the time the transverse flute was not yet as common in England as elsewhere. Especially among amateurs, the recorder enjoyed still considerable popularity, and since the late 17th century the violin had also been played frequently, especially thanks to the Corellimania that spread across the country in the early 18th century.

The Op 4 dates from 1745; the title-page is the same as that of the Op 1, again referring to three different ways of performing them. This collection comprises the more conventional number of six sonatas.

Bisotti states that they show a development from the Baroque style to the galant idiom. That is certainly right, as here graceful melodies are dominant. However, the differences should not be exaggerated. One of the features of the galant style was to end a sonata with a minuet, often with additional variations. In the Op. 1 four of the eight sonatas end with a minuet; in another sonata, the minuet is the penultimate movement. Two minuets are followed by variations, and so is the gavot that closes Solo No 7. In Op 4 four movements end with a minuet, two of them with variations. All the sonatas in both sets are a mixture of the sonata da chiesa and the sonata da camera. The Solo No 7 just mentioned is a good example, as it consists of largo, allegro, siciliana and gavot.

A few observations should suffice to prove that these sonatas deserve the interest of performers and listeners. The Solo No 2 from the Op 1 consists of two sections: it opens forcefully with an adagio staccato, followed by an expressive affettuoso. The adagio from the Solo No 3 in this same set includes some chromatically ascending figures. Notable are the broad gestures of the adagio that opens the Solo No 4. The opening largo from the Solo No 7 is dominated by dotted rhythms. This sonata is one of the highlights of the Op 1, also because of the splendid gavot with variations.

Especially the sonatas of the Op. 4 often remind me of Handel. These are splendid examples of the galant idiom, in which the melody has the main say. That does not mean that they are superficial; apart from the fact that Stanley effectively uses the possibilities of the transverse flute, the slow movements are certainly not devoid of expression, and the fast movements are full of esprit.

That comes off to the full extent in these performances. Daorsa Dervishi, who kindly made this production available for reviewing, is probably the first performer of early music from Albania that I have encountered. She founded several ensembles, among them the Albanian Baroque Ensemble. How nice to know that there is some kind of Baroque movement in Albania. Ms Dervishi is an excellent performer, and it is great that she has turned to the unknown sonatas by Stanley which fully deserve a complete recording. This has resulted in a passionate interpretation, covering the whole palette from the powerful to the tender, doing full justice to these fine pieces. She has found the perfect partners in Alessia Travaglini and Nicola Bisotti.

I greatly enjoy these recordings, thanks to both the quality of Stanley’s sonatas and the outstanding performances by Daorsa Dervishi and her colleagues. I urge you to investigate this release. I am sure that it will give you much pleasure and that you will regularly return to it.

Johan van Veen

www.musica-dei-donum.org

twitter.com/johanvanveen

Previous review: Jonathan Woolf (November 2023)

Buying this recording via a link below generates revenue for MWI, which helps the site remain free