Robert Schumann (1810-1856)

Violin Sonata No 1 in A minor, Op 105 (1851)

Violin Sonata No 2 in D minor, Op 121 (1851)

Violin Sonata No 3 in A minor, WoO27 (1853)

Alina Ibragimova (violin)

Cédric Tiberghien (piano)

rec. 2023, Henry Wood Hall, London

Hyperion CDA68354 (72)

Half a century ago Schumann’s three violin sonatas constituted an entirely unknown quantity for gawky teenage classical buffs such as this reviewer. Given that they were all products of the period directly preceding the composer’s well documented rapid psychological decline, it came as no surprise when I recently happened upon a fairly stereotypical justification for their neglect at that time. Among forty-odd pages devoted to the composer’s chamber music (in Robert Schumann – The Man and His Music – a fascinating if dated symposium published in 1972 and edited by the great Alan Walker) the late composer John Gardner tellingly required just five brief paragraphs to rather cursorily dismiss the significance of the sonatas. His starting point was a quotation from the once famous Anglo-American violinist Harold Bauer who had taken it upon himself to produce a performing edition of Schumann’s first two sonatas, opining that they “…suffer from ineffective handling of the technical resources of the respective instruments. Passages which seem to call for violin tone are frequently given to the piano, and vice-versa. The same notes are frequently doubled…causing a dull tone which forbids the requisite dramatic intensity…” Arguably one had to wait until 1986 for a recording of Opp 105 and 121 which really put this kind of received stupidity to bed – Kremer and Argerich’s blazing DG account liberated the logic from Schumann’s supposedly deranged scores and their performances still sound terrific four decades later.

It took another quarter century before the sonatas (by then including the apparently unyielding and gnomic third) truly caught on; and so it is that in recent times we’ve been blessed with a run of fine recordings which have sought to recalibrate the sonatas’ weave of hellfire and hallucinatory transcendence. Among these my favourites have been those by Tetzlaff and Vogt (Ondine). Widmann and Varjon (ECM New Series – review) and Maalismaa and Holmström, using historical instruments (Alba – review). I am delighted to report that I have found this new Hyperion recording by the well-established firm of Alina Ibragimova and Cédric Tiberghien possibly even more congenial, although frankly I am reluctant to rank four superb sets whose formal and sonic characteristics diverge considerably. Whilst such a judgement is inevitably personal it does perhaps provide some vindication of a trilogy which finally seems to have acquired a degree of credible interpretative variation.

In 2019 Hyperion released this pair’s readings of the three Brahms sonatas (review) – I must admit to finding them rather bland at first hearing (the competition in the case of these works is obviously far more fierce) – inevitably the measured elegance of Ibragimova’s and Tiberghien’s playing (and Hyperion’s sonics) grew on me over time and it’s now one of my go-to versions – I find the second sonata is especially compelling. In the case of Schumann’s first sonata it really didn’t take long for me to fall under the spell of the portentous melancholy of its first movement’s serpentine opening theme, Ibragimova’s violin releasing a shimmering liquidity which is so apt for the strangeness of the material. This is ideally balanced by Tiberghien’s fluid, flexible contribution, oscillating seamlessly between reticence and urgency. The Allegretto central panel emerges as shyly demure with a tang of the diabolic in its central scherzo section. As ever Ibragimova’s quiet playing is a particular delight. There is a teasing hint of the sinister in the scurrying figure which opens the Lebhaft finale– brief episodes of light and tenderness intervene but a darkness permeates throughout thanks to the recurrence of the agitated theme and the imaginative pigmentations of the performers. It’s a deft, rounded conception of a sonata which always seems to fly by yet seems far more substantial in its mysterious implications than its dimensions might suggest.

To my ears the most striking and attractive feature of this issue is evident from the first bar of the first sonata and unfailingly present until the final decay of the third. It’s the unusually alluring blend of Ibragimova’s characterful and trusty 1570 Amati and Tiberghien’s remarkably atmospheric instrument which is identified rather coyly in the booklet as a Bechstein, with no reference whatsoever as to its provenance. (Reviewer’s note: I did seek clarification from Hyperion, but by the time I needed to file this copy they hadn’t responded. Whilst I have no claim to expertise in these matters, I did a bit of digging around among other Tiberghien discs on my shelves; he plays a lovely 1899 Bechstein on his fine recording of Brahms’ Viola Sonatas with Antoine Tamestit for Harmonia Mundi – there are moments which suggest it could possibly be the same instrument….however this might be wild speculation on my part so any enlightenment from those who might know would be gratefully received.) In any event these instruments seem perfect for Schumann, they’re just as convincing as Maalismaa’s and Holmström’s historical instruments on the aforementioned Alba disc although timbrally they are very different.

The extensive tonal palettes of these instruments emerge even more clearly in Schumann’s ‘Grand’ second sonata, Op 121. The jagged initial chords project an apt and imposing Bachian feel, and yield to another long, sepulchral melody lovingly revealed by Ibragimova which declines to a whisper, before this huge movement segues into the subsequent Lebhaft section, opening up a vista of enormous emotional range. Slivers of violin melody are reflected in the piano part and resurface in glowing autumnal hues on the Bechstein. Dramatic and big-boned as this music is at no stage do Ibragimova and Tiberghien lose sight of the tightness of the Schumann’s conception. In a characterful note, Laura Tunbridge refers to the rhapsodic character of the violin’s material, yet familiarity confirms a far more coherent and appealing structure than Schumann was initially credited with during the first century of the sonata’s existence. The terseness at the core of the scherzo (marked Sehr lebhaft) is aptly accentuated here to more effectively draw out its intermittent rays of light, not least the resplendent chorale with which it concludes. The slow movement (marked Leise, einfach – quiet, simple) could not be projected more tenderly – the restraint is both affecting and perfectly judged. Frankly I don’t think I have ever heard this delightful panel played with more grace. Nor is the contrast with the rolling and rising agitation of the finale excessively overwhelming, indeed the playing teases out the subtle, unpredictable modulations at the movement’s core. Ibragimova and Tiberghien’s account of a work which can frequently seem sprawling is outstanding; judiciously measured, beautifully shaded and utterly convincing.

Whilst Schumann’s pair of 1851 sonatas have finally been accepted into the standard repertoire, his final essay in the form remains the elephant in the room. One cannot help but wonder to what extent the rather piecemeal circumstances behind its conception are responsible. Its even numbered movements were devised as part of the so-called F-A-E sonata, the collaborative work Schumann devised with Brahms and Albert Dietrich to mark Joseph Joachim’s 22nd birthday in 1853, but whilst the first movement and scherzo emerged only a short time afterwards to complete what became the third sonata, history has been far less kind to the work and in so doing has arguably exaggerated its diffuse, apparently disconnected form and meaning. Rightly or wrongly I have come to hear Schumann as a disruptor, an experimenter, a risk-taker; after all, what on earth must those early episodic piano masterpieces such as Papillons or Carnaval have sounded like to contemporary audiences in the 1830s? It is the density and concentration of memorable ideas that make them the masterpieces they are and whilst the third sonata may not contain content of that calibre the spirit behind Schumann’s modus operandi seems to be similar – it remains a fascinating and mysterious conception in any case and in the context of his impending decline it proves no less unsettling in its own way than his broadly contemporary Geistervariationen for piano. Ibragimova’s and Tibhergian’s impeccably weighted, phrased and coloured account only reinforces this view. Those opening chords at the sonata’s outset sound truly dark, even sour here, the ensuing pulse suitably disrupted and unstable – even when the movement seeks to settle it doesn’t quite manage it. Ibragimova and Tiberghien somehow convey a sense of going round in circles which I find convincing and moving. Consequently the Intermezzo in this reading – birthday gift or not – seems unbearably sad, a sense underlined by Tiberghien’s muted pastel tones. The scherzo gravitates from swagger to stagger, back and forth. The finale radiates defiance, with Ibragimova’s ravishing colouration adding up to the polar opposite of monochrome. Sure it’s a bit of an awkward work. In my view it’s utterly perfect in its imperfection. These two really nail its weirdness.

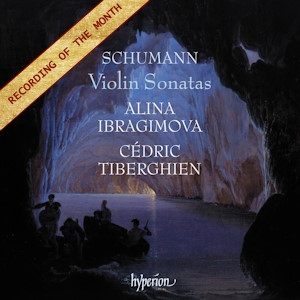

Andrew Keener’s production is a model of lucidity, notwithstanding the opacity of certain elements of Schumann’s design. Laura Tunbridge’s splendid note is effortlessly entertaining and musicologically helpful. On this occasion a bit more information about the piano would have spared my wayward speculation and amateurish detective work. Heinrich Jakob Fried’s murky masterpiece The Blue Grotto at Capri represents an excellent pick for the artwork. Neither aficionados of late Schumann nor newcomers to its unique allure need hesitate.

Richard Hanlon

Buying this recording via a link below generates revenue for MWI, which helps the site remain free