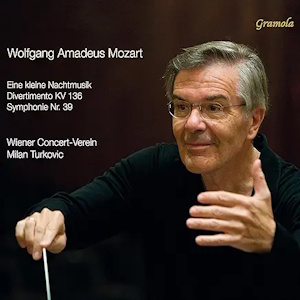

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791)

Serenade No. 13 in G, K525, ‘Eine kleine Nachtmusik’

Divertimento in D, K136

Symphony No. 39 in E flat, K543

Wiener Concert-Verein/Milan Turkovic

rec. 2023, Vienna, Austria

Gramola 99322 [65]

This CD is unusual. Its well-balanced programme by Milan Turkovic conducting the Wiener Concert-Verein offers orchestral pieces in different genres, illustrating Mozart’s mastery of the distinctions between them and finally, in the symphony, his ability to blend the characteristics. For every work I focus on one or two movements and compare Turkovic with other recent recordings on modern instruments. Turkovic’s CD shows Mozart maturing from a divertimento written at 16 to a serenade at 31 and a symphony at 32 years of age. Given this, I’m sorry Turkovic starts with the serenade. His Divertimento 1, as Mozart titled it, is a bright and breezy curtain-raiser. Placing it after the greater variety of mood and suavity of Eine kleine Nachtmusik makes it somewhat of a let-down. I recommend playing tracks 5-7 before 1-4.

In the first movement of Divertimento 1, I admire the shining silkiness Turkovic creates, even in its cheeky appoggiaturas. More delightful still is the courtly interplay he reveals between first and second violins. The second part is cloudier but still courteous in its exploration as in the development when D major turns to D minor (tr. 5, 2:37), yet its suddenly expansive, forlorn first violins’ arioso is offset by the second violins’ running semiquavers earnestly getting on with it.

I compare this with Friedemann Eichhorn directing the Kurpfälzisches Kammerorchester Mannheim, published 2024 (RBM 463032, download only in the UK). This sounds like a smaller group than Turkovic’s, yet plays with more gusto. Eichhorn’s early appoggiaturas are more combative and his running semiquavers grittier. He gives the lower strings’ entries more attention so the twists in harmony are more spotlit. A weakness, however, is a playing time of 3:43 in comparison with Turkovic’s 6:08. This is because he omits the repeat of the second part, though plays that of the first part. This unbalances the movement’s presentation, as the second part has more varied music, containing the development and coda. In sum, Eichhorn is more thrilling; Turkovic’s more rounded approach is more satisfying.

Turkovic ideally catches the delectable, fastidious intricacy of the Andante second movement, its running semiquavers gently ambling. The highlight is the sheen Turkovic brings to the first violins’ descant melody. Eichhorn’s forceful phrase openings, as if marked sforzando rather than p, do not suit a movement which should always remain graceful.

In Serenade 13, Eine kleine Nachtmusik, Turkovic presents the Rondo finale in a largely exquisite, feathery manner with a light and sportive, soft opening, the first violins’ melody floating over the running quavers of the inner parts. Turkovic’s balance is excellent yet I feel that his kid-glove treatment is a little overdone. The sudden f in the second strain (tr. 4, 0:13), with all the strings engaged in running quavers for the first time, should have more impact. In the sole episode (0:24) Turkovic ensures that all is delicate, soft and graceful. His development (2:13) is stressful, but still lightly so, a stylish approach that I feel is defensible. As the coda progresses, the inner parts are more marked and resolute, the second violins add belligerently to the first violins’ motif (5:00),the cellos get involved and finally dovetail the first violins. All this is admirably clear from Turkovic, but I wish it was just a shade more fervent.

I compare this with the Münchener Kammerorchester conducted by Enrico Onofri, recorded 2023-4 (Harmonia Mundi HMM 90539697). The playing here is less beautiful than Turkovic’s but Onofri brings more edge and a sense of celebration, with more discernible dynamic contrasts and engagement in that suddenly louder second strain and later sforzandos. Where Turkovic is quite rarefied, Onofri is purposeful and adventurous.

Now the pièce de résistance, Symphony 39, and my focus is on the first movement. This is Mozart’s last symphony with an introduction, yet with its own distinctive, fundamentally happy, character, the use of clarinets rather than oboes a key influence. The opening is from Turkovic a grand and weighty tutti, but an immediate soft response from wispily descending violins is not unlike those in Divertimento 1, except these descents are tauter, being in demisemiquavers rather than semiquavers, and the aggregation of tension, which Turkovic displays well, makes for a very different atmosphere. Why? To usher in the total contrast of the relaxed magic of the first theme proper on first violins (tr. 8, 1:44). I like the ambience Turkovic creates, so the next tutti is swept forward in a glow, though those violins’ descents, now in semiquavers, should ideally be more clearly articulated, perhaps the difficulty being one of a fairly full acoustic, the woodwind contribution very clear. This is the downside of a recording moving from a string orchestra to a full, albeit chamber, one. A gracious, winsome transitional theme softly slips in (3:22). Its latent energy is now surprisingly and splendidly worked up by Turkovic to a sunny heroic grandeur (3:39) to end the exposition. The development (6:22) Turkovic reveals as a grim progress halted through the Haydnesque genius of a silent bar (7:10), then the recap with those violins’ descents clearer and the peroration is well done.

I compare this with Petr Popelka conducting the Norwegian Radio Orchestra, published 2023 (Lawo LWC 1258). In a drier acoustic, he benefits from a more open perspective, achieving more clarity in dynamic contrasts and a touch more in those descending violins. In the introduction the timpani articulation is crisper and more galvanic. In sum, it is a fresher sound than Turkovic’s, but Popelka’s approach to the music seems to me more distanced and dispassionate than Turkovic’s greater display of tension and heart-on-sleeve. Popelka’s development doesn’t convey Turkovic’s struggle. Thus, Turkovic’s more equable approach overall proves more assuring in clarifying that the movement has a fundamental serenity.

Turkovic’s CD featuring different orchestral forms has two advantages: showing that Mozart was masterful in them all and in Symphony 39 that he can mix them. The Minuet (tr. 10) is divertimento-like, its violins’ running quavers bounce rustically along upheld by the wind repeated crotchets. The Trio (1:44) is closer to a serenade, basking in the first clarinet’s glowing song, yet then infuses the more contrasted, deeper thoughts of the symphony as the first violins’ second strain (2:10) muses over more serious aspects of life. Turkovic equally enjoys the Minuet’s variety between the joie de vivre bluster of the wind and graceful suavity of the first violins. For me, he overdoes the Trio’s relaxation in making it slower, which is not marked, but he can legitimately point out that it is based on a real Ländler tune.

Michael Greenhalgh

Buying this recording via a link below generates revenue for MWI, which helps the site remain free