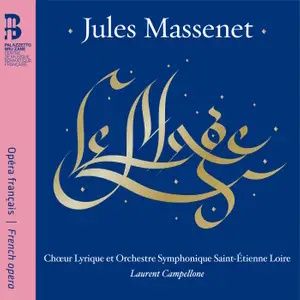

Jules Massenet (1842-1912)

Le mage, opera in five acts (1891)

Anahita: Catherine Hunold (soprano); Varedha: Kate Aldrich (mezzo soprano); Zarâstra: Luca Lombardo (tenor); Amrou: Jean-François Lapointe (baritone)

Chœur lyrique et Orchestra Symphonique Saint-Étienne Loire/Laurent Campellone

rec. live, 11 November 2012, Grand Théâtre Massenet à Saint-Etienne, France

Includes 152 page book

Bru Zane ES1013 [2 CDs: 139]

While researching my survey Recordings of fifteen lesser-known Massenet Operas I was surprised to discover that this recording of a live concert performance of one of Massenet’s most neglected operas had never been reviewed here on MusicWeb. I did not include it in that survey so am remedying that omission here. It was issued in 2013 by Bru Zane in a limited edition of 3000 books containing two CDs, and hardcover copies are still available; it can also be streamed and downloaded.

The opera was composed in the midst of the most successful run in Massenet’s career, premiered between Esclarmonde and Werther; it was well received and ran to thirty-one performance, yet apart from this revival it has since been mostly ignored. The reasons for this are intriguing; after all, it was in the exotic-Romantic French Grand Opera genre which had served Massenet so well for Le roi de Lahore and Hérodiade, combining both supernatural and religious elements with warfare and a love story as per Le Cid – which it in many ways resembles. Another reason for that failure could reside in the supposedly inferior quality of its music and dramaturgy but Massenet was in full creative flow and the plot is perfectly accessible – nowhere near as complicated as some operas. His librettist, Jules Richepin, was a successful poet, novelist and dramatist who collaborated with many prominent musicians of his day – and in his essay, the conductor, while no doubt rightly dismissing any philosophical connection between the opera and Nietzsche, asserts that with Le Mage, Massenet “had a perfectly balanced drama: heroism plus exoticism plus Republican values” in which its hero defies monarchical despotism and proclaims “ a new order of truth, liberty, equality and fraternity”. A final possibility is that the audiences and critics were expecting something more like Manon rather than what looked like a return to an older formula – yet having been bowled over by Parsifal in Bayreuth, Massenet consciously catered to the increasing public taste for “Wagnerism” rather French lyricism, making both musical and thematic references to that ‘Bühnenweihfestspiel’ – especially in the last act. I would also add, however, that very little of what I hear lingers in my memory; Massenet’s melodic gift seems periodically to have deserted him for quite long stretches – which may partially account for the opera’s neglect. Anyway, whatever the reasons, the subsequent demise of Le mage was almost complete and I was keen to discover why it appeared to be a casualty of history.

The work opens very promisingly with a brooding prelude depicting the despondency of the captive Turanians, the excellent tenor Julien Dran – Alain, in Bru Zane’s Grisélidis – singing mellifluously as a prisoner. This is followed by some splendid military fanfares. Jean-François Lapointe the High Priest Amrou enters demanding obeisance; he is mild and unobjectionable of voice, but his low notes are weak and he is without much presence or menace. His daughter, the wicked Varedha, is something of an Amneris, her love for the victorious commander Zarâstra being unreciprocated; she is sung by mezzo-soprano Kate Aldrich, who acts convincingly and whose voice is powerful, but it tends to screech and too often exhibits an obtrusively pulsing vibrato, especially on loud, high notes.

Lead tenor Luca Lombardo sings Zarâstra, the eponymous hero. This issue is a recording of the second of two concert performances; an announcement was made before the first that despite being ill Lombardo would bravely battle on so as not to compromise the project. Be that as it may, while I commend his commitment, I doubt whether he had fully recovered a mere two days later and, ailing or not, I suspect that he could never have properly fulfilled the demands Massenet’s score makes of him. He projects little in the way of vocal glamour or charisma; rather than suggesting a triumphant warrior, his small, dry, nasal tenor creates in my mind the image of a puny male spider about to be devoured by his much bigger potential mate. His top notes are strained and he is overpowered by Aldrich. He has some potentially effective arias such as the Act II “Soulève l’ombre de ces voiles” but cannot deliver them adequately. My disappointment is compounded by Catherine Hunold’s harsh, hard soprano, singing Anahita, his beloved; her basic tone is impure and scratchy. The lack of vocal appeal in the quartet of principal voices makes it hard to gauge how good Massenet’s music actually is, as I do not think it enjoys optimum advocacy here; all I can say is that I derive little pleasure from the lovers’ duet until suddenly Julien Drans’ tenor reappears in the sound picture and once again my ears prick up. The same is true of the dramatic confrontation between Amrou and Varedha in the opening of Act II, which again echoes Verdi’s Aida, this time the father-daughter scene between Amonasro and his daughter; it lacks vocal punch on Lapointe’s part and when you hear Florian Sempey ‘s Herald in the opening of the next scene it is clear that his more resonant baritone would have been better suited to singing Amrou rather than the two supporting roles he undertakes here. The King is also poorly sung: rocky, throaty and blaring.

The orchestra is very good and it is expertly conducted; there are some really striking, atmospheric preludes for Acts II, III and IV, and the chorus is fine: energised and emphatic. That impressive thunder and lightning introduction to Act III, its ambience intensified by fervently praying chorus, is let down by Lombardo’s bleating tenor. The compulsory ballet at the start of Act IV is anodyne and of course just holds up the action for the sake of a spectacle to satisfy the patrons who demanded to ogle the ballerinas. Anahita’s screamed “Non ! non ! non !” at the climax is just horrible – a pain in the ears. There is little point my tracing, act by act, instances where I find the opera disappointing; you get the picture – and there you have it: my own conclusion is that a lack of memorability in the music itself is compounded by the poor singing in this performance; certainly its resurrection here over a decade ago did not precipitate a revival. I am sorry if I come across as sour in my response; I can only point to my warm endorsement of the recent Bru Zane Grisélidis (review) in which I found it to be very satisfactory all round. You may judge for yourself, as you can in fact hear the complete work on YouTube and a French libretto with an English translation is available if you register free of charge on the Bru Zane website. You might be less critical than I; in any case, this is the only way we may get to hear this rare work and everything else – thorough, elegant presentation, flawless production, excellent sound and orchestral playing, and conducting of the highest order – is up to Bru Zane’s usual impeccable standard.

Ralph Moore

Buying this recording via a link below generates revenue for MWI, which helps the site remain free

Other cast

Le Roi d’Iran: Marcel Vanaud (baritone); Prisonnier Touranien: Julien Dran (tenor); Chef Touranien/ Hérault: Florian Sempey (baritone).

Contents of book

Arthur Pougin, Jules MassenetJean-Christophe Branger, ‘Le Mage’: a justified revival

Michela Niccolai, The visual aspects of ‘Le Mage’

Laurent Campellone, ‘Le Mage’, a Nietzschean opera?

Jules Massenet, My Recollections

Synopsis

Libretto