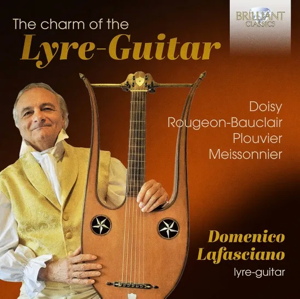

The Charm of the Lyre-Guitar

Charles Doisy (c.1748-c.1807)

Douze Petits Airs faciles (1801)

A.A. Rougeon-Bauclair (17??-18??)

Douze Walses et un Thème variè

Pierre-Joseph Plouvier (c.1750-1826)

Allemandes, Rondeaux, Sauteuses et Anglaises

Jean-Antoine Meissonier (1783-1857)

Quatre Nocturnes

Domenico Lafasciano (lyre-guitar)

rec. 2023, Milan, Italy

Brilliant Classics 97346 [75]

Here is a rarity, or perhaps one might say an intriguing oddity: a disc devoted to an instrument (the lyre-guitar) which was fashionable for a few decades and has since been largely forgotten. Furthermore, all the music played on the disc is the work of four minor composers, all of whom are now very little-known.

First, the instrument. The obvious feature which distinguishes the lyre-guitar from the guitar of the period of its popularity (roughly 1780-1830) is its shape, rather than its sound. Like the normal guitar it has six strings, but its fretboard is flanked by two curved arms, which are reminiscent of the classical lyre. It is symptomatic that the instrument’s probable inventor (c. 1780), the Parisian luthier Pierre Charles Mareschal should have described it as a “lyra anacréontique”, thus associating the instrument with the work of the Greek poet Anacreon, who chiefly wrote songs in praise of love and wine. Some later luthiers added more strings to the instruments they made, sometimes as many as twelve. On this disc, Domenico Lafasciano plays a six-string lyre-guitar of 1806 made by Henry Lejeune of Paris.

The invention of the lyre-guitar or lyra anacréontique, chimed with the neoclassical tastes of the aristocratic society of France in the years either side of 1800, as illustrated in some of the works of artists such as Jacques Louis David (1748-1825) and Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres (1780-1825) or an influential poet like André Marie Chénier (1762-1794). The lyre-guitar could appear as part of the décor of a fashionable salon, particularly one with musical aspirations – even if was never played. It could also serve as a prop in portraits, such as this 1804 image of ‘Madame Lamoyer holding a lyre-guitar’ by Antoine Vestier. Napoleon took an interest in the instrument. There is, for example, a drawing by Ingres of the family of Lucien Bonaparte, made in 1815, and now in Harvard, which includes a young woman playing the lyre-guitar Others known to have played the lyre-guitar included Marie-Antoinette and George Sand. In Austria, Schubert’s friend, the singer Johann Michael Vogl sometimes accompanied himself on the instrument. Among significant musicians to have played the instrument, one might mention the Italian Mauro Giuliani (1781-1829); widely recognised as a virtuoso of the ‘conventional’ guitar, he gave a concert on the lyre-guitar in Naples in October of 1826.

My favourite amongst the relevant paintings is a very striking work by Goya painted in 1805, The Marchioness of Santa Cruz, in which the duchess is painted reclining on a couch of red velvet, holding a lyre-guitar in her left hand. The presence of this instrument is emblematic of her status as a patron of poets and musicians; she appears to be wearing a crown made of grape leaves which may be an allusion to Anacreon and the lyra anacréontique.

Sadly, all this fascinating background to the instrument and its symbolism, makes the music recorded here something of an anticlimax. The best one can say of what is to be heard on the disc is that it is a mildly pleasant way of passing an hour and a quarter. In common with one or two other lyre-guitars which I have heard, the instrument played (very well) by Signor Lafasciano is relatively dull in sound, largely lacking the brightness of sound which the best guitars of the same period possess. The recital opens with ‘Douze Petits Airs faciles’ by Charles Doisy. As the title suggest these short and ‘easy’ airs are far from sophisticated. Doisy was the author and publisher of a method book, Principes généraux de la Guiutarre å et å six cordes et de la Lyre, first published in 1801 (and dedicated to Napoleon’s first wife, Josephine). They are, indeed, practice pieces which don’t transcend such a role. Having listened several times to these ‘Airs’, not one of them has lodged in my memory.

There is more musical substance in the second set of miniatures on the disc – the ‘Douze Walses et un Thème varié’ by A.A. Rougeon-Beauclair. There is a certain subtlety in what was the composer’s Opus 8, more than one hears in the instructional pieces by Doisy. This is more inventive writing, with some genuine sophistication.

Plouvier’s set of ‘Allemandes, Rondeaux, Sauteuses et Anglaises’ has the virtue of variety, in form, rhythm and tempo. There are twelve short pieces, the longest a mere two minutes and eleven seconds. These pieces are decidedly attractive and make for rewarding listening. This is a collection of interest, perhaps the highlight of the disc.

The recital closes with Meissonier’s ‘Quatre Nocturnes’. All four pieces are single-movement rondos, the first marked gratiozo, the second escherzando, the third allegretto con giusto and the last andante expressivo – Andantino. All are interesting, if not especially remarkable.

Available biographical information on these four composers is sparse. Of Doisy, Domenico Lafasciano writes “Unfortunately, we do not know much about the life of the Paris-born Charles Doisy”. He seems to have been a publisher and a teacher of music as well as a composer. In 1797 he opened a music shop in Paris. His Grand Concerto for guitar and strings (c.1802) was one of the earliest works in that genre. Lafasciano’s discussion of Rougeon-Bauclair begins by telling the reader that he “remains a figure shrouded in mystery” and most of his note on the composer is concerned to discuss quite what the composer’s name was; he tells us that Choron’s Dictionnaire historique des musiciens refers to one Rougeon-Beaclair as“a Paris-based postal worker. Lafasciano refers to several other reference works before making mention of a death-certificate (of 1839) in the name of Alexandre Alfred Rougeon-Bauclair; this was perhaps the composer?

Lafasciano is also obliged to write that “We know very little about Pierre-Joseph Plouvier, a guitarist, flautist and composer who was born in Gand (Belgium) and settled in Paris, where he worked as a guitar teacher”. He moved to Brussels c.1804 and worked there as a music publisher. Amidst all the uncertainty and confusion surrounding the first three composers on this disc, the situation is somewhat clearer where Jean-Antoine Meissonier is concerned.

Meissonier was born in Marseilles; he left that French port at the age of sixteen. He made his way to Naples, intending to study guitar and composition there, against the wishes of his parents, who wanted him to get a job in one of the many businesses active in Marseilles. After a few years spent in Naples, Jean-Antoine Meissonier returned to France, but made his way to Paris rather than Marseilles. Initially he worked as a guitar teacher and a composer; in 1814 he established a music publishing house of his own. He was joined in Paris by his younger brother Jean-Racine (the two have sometimes been confused), who assisted him in the publishing business. Jean-Antoine wrote a substantial body of music for guitar, including sonatas, transcriptions of popular operatic arias, sets of variations et al. He also gave recitals in Paris. It is interesting that he often advertised his compositions as suitable both for guitar and lyre-guitar, such as his Grande Sonate en Rondeaux pour Lyre ou Guitar.

The rise (and fall) of the lyre-guitar was a striking cultural event (which I have tried to put into context) and this is a pleasant introduction to the instrument and some of its music (though the purely musical rewards are not great).

Glyn Pursglove

Buying this recording via a link below generates revenue for MWI, which helps the site remain free.