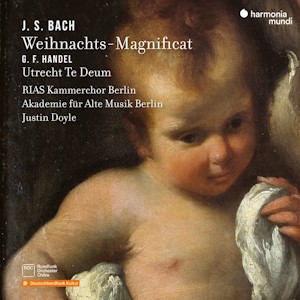

Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750)

Magnificat in E flat (with Christmas interpolations) (BWV 243a)

George Frideric Handel (1685-1759)

Te Deum in D ‘Utrecht Te Deum’ (HWV 278)

Núria Rial, Marie-Sophie Pollak (soprano), Alex Potter (alto), Kieran Carrel (tenor), Roderick Williams (bass)

RIAS Kammerchor Berlin

Akademie für Alte Musik Berlin/Justin Doyle

rec: 2024, Jesus-Christus-Kirche, Berlin

Texts and translations included

Reviewed as a download

Harmonia Mundi HMM902730 [57]

When I look at programmes of public concerts, I often wonder in what way the works that are performed, may be connected. What’s the story? It seems that sometimes performers just put pieces together which they like or include a piece a soloist loves to play. In the case of Romantic repertoire, it may be my ignorance that I don’t see any connection, but it also happens in the kind of music I am used to. The present disc is a case in point. What have Bach’s Magnificat and Handel’s Utrecht Te Deum in common that they are brought together in one recording? It is a mystery, and Bernhard Schrammek, in his liner-notes, does not make any attempt to connect them. So we have to take both items as they come.

For many centuries the Magnificat or Song of Mary, one of the canticles from the Bible, was one of the main parts of the liturgy. It was sung at the end of Vespers, preceded and followed by an antiphon which linked it to the time of the year. This explains why we know so many settings of the Magnificat from the Renaissance; Nicolas Gombert, to mention just one example, wrote a series of eight settings in the different church modes. In Protestantism, where the Virgin Mary takes a fundamentally different place, it was connected to the Feast of the Visitation – Mary’s visit to her cousin Elizabeth shortly after the Annunciation – and, following logically from this, Advent and Christmas.

Bach composed only one setting of this text. A performance on Christmas Day in 1723 – his first year as Thomaskantor in Leipzig – is documented, but it seems likely that he wrote it for the Feast of the Visitation on 2 July of that year. For the performance at Christmas, he included four hymns which linked the work to the day . This was in line with a tradition in Leipzig to add so-called laudes, which is rooted in an age-old practice of adding tropes to an existing text. One can see also a link here with the liturgical tradition of adding an antiphon as mentioned above.

I don’t want to discuss here at length the issue of the number of singers that should be involved in performances of Bach’s sacred works. However, even if one takes Bach’s often quoted wishes about the number of singers he should have at his disposal literally, a choir of 32 singers is far too large. Moreover, in Bach’s time there were no soloists; the solo parts were sung by members of the choir. That is how conductors like Philippe Herreweghe and Masaaki Suzuki perform Bach’s sacred music. From that angle this performance is ‘old-fashioned’.

Although the RIAS Kammerchor is too big, it sings very well and the choruses are quite transparent; the text is clearly intelligible. That also goes for the contributions of the soloists. Their diction and articulation is excellent, and their treatment of dynamics nicely differentiated. In the ensembles, the voices match perfectly. It is rather odd, though, that the trio ‘Suscepit Israel’ is sung by the respective sections of the choir rather than the soloists. Another point of criticism is that the Latin text is pronounced the Italian way, which is certainly not how it was done in Bach’s time in Leipzig.

The Utrecht Te Deum & Jubilate were written at the occasion of the Peace of Utrecht, which was definitely something to celebrate. It ended a thirteen-year period of war, the War of the Spanish Succession, which was tearing the whole of Europe apart. About 400,000 people had been killed in the process. As a result of the treaty, a balance of power was established in Europe which would last until the French Revolution, and which took the continent into more or less smooth waters. Wars still took place. but were mostly limited to parts of Europe.

In March and April 1713, the Treaty of Utrecht was to be signed, but Handel had finished composing the Utrecht Te Deum in January of 1713. It was to be performed in St Paul’s Cathedral in London, probably in March or April, as the rehearsals took place in March, but it was only in July that a service of thanksgiving was held. In the meantime, Handel had also written the Utrecht Jubilate, and therefore these two works are usually performed together, which was also in line with tradition. They are different in that the Te Deum is mostly written for choir, with relative short episodes for solo voices, whereas there are more extended solo sections in the Jubilate. The scoring is the same as Henry Purcell’s Te Deum & Jubilate of 1694, and both the role of the trumpets and the fact that the choir is mostly divided into five parts show Purcell’s influence. Handel had clearly studied his music closely and took inspiration from it.

The text of the Te Deum, which opens with the words “Thee, O God, we praise”, is assumed to date from the fourth century, but may be much older. It takes a central place in the Ambrosian hymnal and disseminated across Europe. In the course of history the text was set many times, often in connection with official occasions, such as a peace treaty or a military victory. Whereas elsewhere the Latin text was used, for instance by Marc-Antoine Charpentier, Handel used the text from the Book of Common Prayer used in the Anglican church. The Utrecht Te Deum was Handel’s first major sacred work in English. It made a strong impression: it was performed in St Paul’s Cathedral every other year – in alternation with Purcell’s setting – during the annual Festival of the Sons of the Clergy, until it was replaced in 1743 by the Dettingen Te Deum.

It receives an outstanding performance here. The structure is different from Bach’s Magnificat: there are no extended arias, but only short solos, always for more than one voice, from two (To thee all angels cry aloud) to five (Vouchsafe, O Lord). Although I don’t know exactly how many singers Handel had at his disposal for the performance of this work, his choirs were certainly larger than those Bach used in Leipzig, and from that angle the size of the choir in this performance is much less of a problem. The Te Deum was also meant to make an impression, and in this recording it certainly does, thanks to the contributions of soloists, choir and orchestra, and the energetic direction of Julian Doyle.

Johan van Veen

www.musica-dei-donum.org

twitter.com/johanvanveen

Buying this recording via a link below generates revenue for MWI, which helps the site remain free