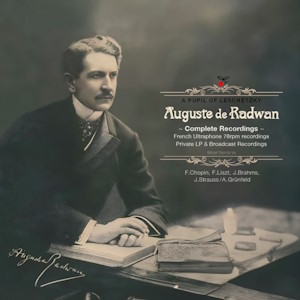

Auguste de Radwan (piano)

Complete Recordings

Henri Gautier (second piano in concerto disc two)

rec. 1932-c.1952, locations not provided

Sakuraphon SKRP78015-16 [2 CDs: 156]

Hisao Natsume’s excellent Sakuraphon label has released six volumes of a projected seven volume series the Pupils of Leschetizky that so far offers selections by pianists born between 1830 and 1896; the 38 pianists featured to date range from the familiar, Ignaz Friedman, Ignacy jan Paderewski, Benno Moiseiwitsch and Elly Ney to unknown names like Louis and Susanne Rée, Celeste Chop-Groenevelt, Herman Osthmeier and Grace Stewart Potter Carroll. In addition a series of CDs focusing on individual pianists from the main collection are planned and the present CD is the first fruit of that project.

Auguste de Radwan appeared on the first disc playing an abbreviated version, just the opening three minutes, of the romance from Chopin’s first piano concerto and I have to say I was quite taken with that disc and wanted to hear more. The resulting complete recordings, issued here on two full discs, are something of a mixed bag. Disc one is dedicated to the series of 78s he recorded for French Ultraphone in the early 1930s when he was in his mid sixties. Disc two features a “private LP” for which there is no date or provenance given and a live recording from 1952 of the second and third movements of Chopin’s E minor concerto on two pianos in which he is joined by Henri Gautier, a French pianist who went on to record Liszt and Debussy. Radwan was in his mid eighties at the time of these recordings and in advance notice of the release Sakuraphon wrote This CD is not recommended for listeners who are not interested in history. Because it was recorded when the pianist was old, there are many mistakes and misrememberings. Fair warning indeed.

When I first saw his name and did a google search I saw little about him as a pianist but references to a 2016 discovery in the National Library of Wales of over 250 letters to Marjorie Hall (1906-1993). She met Radwan when she was studying in Paris in 1926 and though the pianist was nearly forty years her senior they began an affair that lasted until she returned to Wales and the long distance relationship became unsustainable; she became Lady Pryse in 1938. Radwan kept her photo in his wallet until his death in 1957. The booklet fills in other details; he was born in Warsaw but spent most of his life in Paris, studied with Theodor Leschetizky between 1889 and 1894 and toured extensively; as an aristocrat he was welcomed in the salons of Europe and it seems that this was where he was most comfortable. His repertoire was centred firmly on the romantics, especially Chopin, playing both concertos, the second and third sonatas and large portions of the préludes, études, waltzes, polonaises and ballades. That said Brahms was apparently his favourite composer and he also played Liszt including his Bach transcriptions, Mendelssohn, Schumann and others; no mention is made of anything by later composers – Radwan was no pioneer.

Chopin makes up the majority of his recorded legacy and include seven mazurkas; after a 1901 recital he was praised for understanding not only the mood, not only the rhythm but the subtlety of the character of mazurkas and polonaises. Certainly he captures the vigour of the dances and he is admirably lyrical but his emphasis of left hand accents, noted in a 1901 review, is clear in several, particularly op.33 no.3 where a potentially quite beautiful mazurka is marred by the second beat left hand notes. Elsewhere there are felicitous touches that though not written are actually effective, the slower version of the theme of op.33 no.2 when it reappears for example though even here he spoils the effect by putting a chord on the last chord of the piece rather than trusting Chopin’s notes rising into the ether. Op.30 no.4 is somewhat slapdash and he seems reluctant to give the piece time to breathe, rushing through phrases and pauses. None of the études will enter the hall of fame but he plays them decently enough, mostly leaning toward their more lyrical side; otherwise positive reviews noted his technical imperfection and he does occasionally come a cropper, the double thirds passages of op.25 no.6 or the lead up to octave descent of op.10 no.5 for instance but they can be enjoyed beyond these little lapses. Likewise the préludes, especially the F sharp minor and E flat major which he brings off very effectively and for me this set of six contain some of the best playing here. He joins Mischa Levitski and Wilhelm Backhaus in the practice of repeating the first prélude – evidently this was a widespread practice at the time. His A flat étude from the trois nouvelles études is a little stiff but he plays the A flat ballade well with only little slips in the more complex sections.

The Brahms also fares well with a good selection of waltzes that I find reveal more of his dance qualities than do the mazurkas. There is energy and lilt in his rhythms and lightness in his touch, evident in the elfin sixth, even if he is a little heavy handed when a marcato or sostenuto appears. Surprisingly the other works here, the intermezzo op.119 no.3 and capriccio op.76 no.8, are are only their third and second recordings. The intermezzo is perhaps a tad slow for my taste but still graceful and he brings out the meat in the capriccio rather than the fluidity and suppleness that Backhaus, recorded a year earlier brings. The Liszt C sharp minor rhapsodie continues the pattern that can be heard throughout these 78s; he is strong in lyricism and drama but is under some pressure when the real virtuosity kicks in. The early pages have swagger and character but the final pages, for all he keeps going, are scrappy with notes falling by the wayside, as they do in the two, rather abbreviated Strauss transcriptions. These have lots of nice touches, some really delicate playing and a beautiful sense of style but alongside that you have to accept hit and miss left hand bass notes, smudged transitions and many instances where an easier option is taken such as the return of the main theme in Voices of Spring which should be octaves. This is also prime clumsy-bass-note territory. I enjoyed listening to these 78 r.p.m discs, slips, rushed passages, 19th century habits and all but other pianists of the age were on the whole more successful.

I listened to the second disc first which I admit was probably a mistake; I was all prepared for the fact that this was a pianist beyond his prime but the opening E flat nocturne, with stiff and uneven playing that vacillates between the moderately acceptable and fractured rhythms that sound like sight reading, brought one, possibly ungracious thought to my mind – is he really going to try to play Chopin’s G sharp minor étude and Liszt’s 12th Hungarian rhapsodie? Before he gets to that he plays the first three études of op.25 and some of his lyricism shines through even if he is unsteady on the actual technique; the arpeggios that close op.25 no.1 are curtailed and the demisemiquaver passages of op.25 no.3 are beyond him but he does bring in light and shade and some inner voices to balance that. The traits that we heard in his 1930s mazurkas are more pronounced in his later versions of the same pieces; the over emphasis on left hand notes and rushed passages, notably in op.30 no.4. A rather monochrome op.56 no.2 is new to his discography, with several missed notes and ornaments but has a rather beautifully controlled diminuendo to the finish. The Préludes may suffer technically, notably the third which I have never heard slower and the eighth which loses as many notes as he plays but once again he emphasises the lyrical and the dramatic aspects; for all the faults of the eighth he does make a powerful impression. The final étude here is normally called the étude in thirds but alas here Radwan too often plays single notes and the thirds that are there are all too often rather shaky. For some reason the étude fades into silence four bars from the end; I cannot tell whether the recording fades or Radwan simply stops playing. One gets the feeling that he was proud of playing this and the following piece, the Liszt 12th Hungarian Rhapsodie and wasn’t willing to let a technique compromised by age stop him playing it once more for posterity. It is a shame to hear the rhapsodie; Radwan is now simplifying passages or missing things out and after the stretta vivace too much goes wrong for enjoyment. There are moments of grandeur but these are really only flashes of a more vital youth. Of course we don’t know the intention behind this LP. I doubt it was meant for public consumption and was possibly for family or a close circle of friends; while it nice to have the complete Radwan this is not adding to our picture of the pianist.

For all its faults the movements from the Chopin concerto are preferable. It gives us the complete romance for one thing and we can appreciate the qualities that he was admired for in his earlier years, his strong sense of line and a real delicacy at times. The rondo can be enjoyed and there are more correct notes than in the étude in thirds or the rhapsodie; admittedly he slows down for every faster passage and has a memory lapse that Gautier on second piano picks up magnificently and things go smoothly second time around – you wouldn’t know if you didn’t know the score well – but it is a better swan song than the LP would have been and the applause is rapturous and warm hearted.

Presentation is first class as are the transfers; Sakuraphon’s standard packaging is individual sleeves with the CDs pressed to look like vinyl discs, stored in a good quality cardboard sleeve and a fold-out booklet with photos and track listings to surround that. In addition this release has an eight page biography of the pianist in occasionally quirky but perfectly comprehensible English. I would like to claim that Radwan is a pianist that posterity has treated poorly but in truth he is not. Like many pianists of the time his art was captured when he was past his prime but other pianists maintained their prime better. I am grateful to Sakuraphon for giving us an opportunity to hear this lesser light from Leschetizky’s star roster and I am looking forward to more of theses CDs focussing on individual pianists. For those interested in historical pianism this is an interesting issue but for those with a casual interest I would suggest they heed Sakuraphon’s warning; caveat emptor.

Rob Challinor

Availability: Sakuraphon

Contents

Ultraphone 78rpm complete recordings

rec. 1932-33

Frédéric Chopin (1810-1849)

Mazurka No.2 in C sharp minor Op.6 No.2

Mazurka No.21 in C sharp minor Op.30 No.4

Waltz No.2 in A flat major Op.34 No.1

Romance, 2nd movement of Piano concerto No.1 in E minor Op.11

Mazurka No.30 in G major Op.50 No.1

Etude in F major Op.25 No.3

Etude in G sharp minor Op.25 No.6

Etude in G flat major Op.10 No.5

Etude in E flat major Op.10 No.11

Mazurka No.23 in D major Op.33 No.2

Mazurka No.24 in C major Op.33 No.3

Mazurka No.26 in C sharp minor Op.41 No.1

Préludes Op.28 Nos. 11, 19, 8, 1 23, 24

Ballade No.3 In A flat Op.47

Nouvelles étude in A flat major

Johannes Brahms (1833-1897)

Waltzes Op.39 Nos. 1-4, 6-8, 11, 13-16

Intermezzo in C major Op.119 No.3

Capriccio in C major Op.76 No.8

Franz Liszt (1811-1886)

Hungarian Rhapsodie No.12 in C sharp minor S.244 No.12

Johann Strauss (1825-1899) arr. Alfred Grünfeld (1852-1924)

Voices of Spring

Soirée de Vienne

Private LP rec.?

Frédéric Chopin

Nocturne No.16 in E flat major Op.55 No.2

Etude in A flat Op.25. No1

Etude in F minor Op.25 No.2

Etude in F major Op.25 No.3

Mazurka No.2 in C sharp minor Op.6 No.2

Mazurka No.24 in C major Op.33 No.3

Mazurka No.26 in C sharp minor Op.41 No.1

Mazurka No.34 in C major Op.56 No.2

Mazurka No.21 in C sharp minor Op.30 No.4

Preludes Op.28 Nos.1, 3, 7, 8, 23, 24

Etude in G sharp minor Op.25 No.6

Franz Liszt

Hungarian Rhapsodie No.12 in C sharp minor S.244 No.12

Private live recording rec. 6th February, 1952 from les Baux-Sainte-Croix, Chateau de Chamberlain

Announcement (in French) by Charles Oulmont

Frédéric Chopin

Piano concerto No.1 in E minor Op.11 Movements 2 and 3