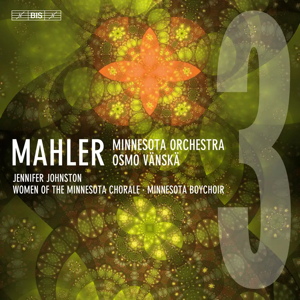

Gustav Mahler (1860-1911)

Symphony No. 3 in D minor (1895-1896)

Jennifer Johnston (mezzo-soprano), Women of the Minnesota Chorale, Minnesota Boychoir, Minnesota Orchestra/Osmo Vänskä

rec. 2022, Orchestra Hall, Minneapolis, USA

Texts in German with English translation

BIS BIS-2486 SACD [36+68]

Osmo Vänskä’s Mahler cycle from Minnesota has received a mixed reception on the MusicWeb site; the Eighth had very positive reviews this year (review ~ review), whereas reactions to the Ninth varied (review ~ review ~ review). This is the concluding instalment and is as impressive as the Eighth; it would seem that over the period of performing and recording these symphonies, orchestra and conductor have increasingly refined and developed their Mahlerian acumen.

I have many favourite versions of this majestic symphony. I recently added Maris Jansons’ live performance from 2010 on BR Klassik (review) to my list, which includes Abbado on DG in 1980, Horenstein, Wit, Tennstedt live in 1986 on the ICA label and Sinopoli in Stuttgart in 1996 – formidable competition.

First impressions are very good – superb, spacious sound, secure, sonorous brass, a sense of coiled expectancy and an aggressive edge to the playing which is most engaging. The angelic woodwind choir and violin solo six minutes in signal the change of mood to the funeral march and the succession of solo instrumentalists – especially the trombonist, R. Douglas Wright – continues to delight with flawless execution of their parts. Vänskä lets rip dynamically – but only sparingly, at judiciously spaced intervals; much of the playing is delicate and his control is such that there are no longueurs in this extensive first movement. That control might seem excessive to listeners who seek more wildness in this music; Vänskä’s emphasis is upon detail and clarity. Having said that, there is plenty of release and abandon in the wild development beginning twenty-four minutes in, before the martial snare drum episode and the reprise of the opening horn motif, exquisitely played by Michael Gast. The climax to the movement could not be more rousing, conveying all the excitement of a live performance even though this was subsequently recorded under studio conditions.

Despite its intermittent grandeur, and even menace, much of this music is charming and bucolic, so the gentleness of Vänskä’s approach pays dividends in the swaying second movement and the faintly macabre dance of the third, where despite the charm he doesn’t underplay the impact of moments such as the chromatic slide on the brass of a minor ninth from high A flat to low G at four minutes in and repeated at 13:09. The offstage posthorn solo is exquisitely and very atmospherically played by Manny Laureano, ethereally removed yet somehow comforting. The coda recaptures a sense of awe and immensity.

The misterioso fourth movement begins so quietly that one strains to hear it but Jennifer Johnston’s clear, firm tones soon kick in. She hasn’t the darkest, most characterful mezzo but it is warm and even throughout its range and her crystalline diction draws the listener in. The “Bim bam” chorus goes swimmingly, both boys and women singing sweetly then swelling the volume impressively in the middle section, and Johnston digs into some nice, resonant middle-voice tones.

However, the hypnotic finale must be the transcendent culmination of this huge symphony and it is here that experience my first slight disappointment with this account. I need my spirit to soar when I hear that music and compared with Abbado, Wit et al, Vänskä seems first to rush the phrasing of the opening and does not achieve their concentration – indeed, he is overall three minutes faster than they but that is not the issue; it is more about how lovingly and tenderly the arcing phrases are shaped and somehow he fails to find the requisite magic that Sinopoli in particular conjures. I played his and Vänskä’s finale back to back to check my response – and yes; there, in Sinopoli’s version, was the emotional intensity I required – in fact, Vänskä is not remotely a rival. Conductors such as Jansons, Tennstedt and Horenstein are actually faster than Vänskä but more successful in exerting a spell – despite the latter two being in sound inferior to this BIS SACD issue. I guess it boils down to what I can only describe as a kind of affective reticence on Vänskä’s part – almost a stolidity – or is it that he is keeping his powder dry for the climaxes at 13:19 and again 21:39, which are certainly powerful, even if they do not rival the cataclysmic impact of Sinopoli’s? That initial coolness is by no means a fatal blow to this performance – just a mild drawback, as the whole is very well played.

The sound quality here is one of its greatest attractions and BIS have already released a box set of all ten symphonies if you want the best modern Mahler on the market in terms of recorded sound – and some fine performances, even if not all are of equal quality.

Ralph Moore

Buying this recording via a link below generates revenue for MWI, which helps the site remain free.