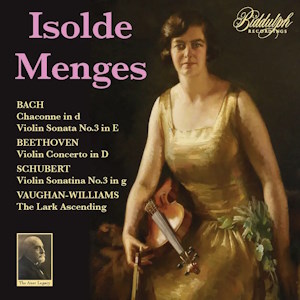

Isolde Menges (violin)

rec. 1922-30

Biddulph 85047-2 [2 CDs: 164]

Isolde Menges (1893-1976) was a buoyant, tonally attractive, technically finely equipped soloist. A pupil of Leopold Auer and very briefly Carl Flesch, she made her concerto debut in 1913 but spent part of the First World War in North America as she had a German father and this caused problems. Her first recordings for HMV were made in 1915 – some have been reissued by APR in their ‘Auer Legacy’ releases – and thereafter she was in the studios until 1930 making several important contributions to the discography. The Great Depression and the HMV-Columbia merger put an end to her recording career until she signed to Decca to make a couple of Dvořák recordings with her own string quartet and augmented sextet. She taught at the Royal College of Music for many years. I once spoke to a pupil of hers who told me that she, by then almost doubled over with arthritis, used to teach by asking him to play then went to her record cabinet, put on her 78 of the piece he’d played, and ‘showed him how it was done.’ Though I’ve also heard that even in old age she could still play flawlessly.

This twofer is the most comprehensive tribute to her artistry that has yet been issued. It stands alongside Biddulph LAB076 which contains her recordings of two Brahms sonatas and the Kreutzer Sonata, with Harold Samuel and Arthur de Greef as her pianists, and that APR release. Crucially this is the first appearance of her Beethoven Concerto since Pearl’s LP transfer and the first appearance of a restoration of her The Lark Ascending. Most of the smaller pieces are also making their first appearance on CD (or indeed LP). A small picture on the booklet cover shows that the twofer has been reissued in Biddulph’s own ‘The Auer Legacy’ marque.

The first disc focuses on her Bach, a known repertorial strength, and Beethoven. The Bach Violin Sonata No.3, BWV1016 has been reissued before, on Koch, in a twofer devoted to Harold Samuel and its nobility of spirit never palls, the collaboration reaching its zenith in the slow movement. The Air in Wilhelmj’s arrangement was a much-recorded piece but Menges’s richly vibrated but elevated conception impresses as does her robust bowing in the Fugue from the Violin Sonata No.1, an acoustic disc from 1922. The Chaconne, recorded on 7 April 1924, is another late acoustic and a premiere recording – Lionel Tertis recorded it on the viola for Columbia later in the year. It’s carefully conceived with no gratuitous accelerandi and without any sense of metricality. It shows her forward-looking conception of Bach and indeed her sense of appropriateness in the repertoire generally. It generates its own logical development. One can sense a side join at around 11.30 because of the increase in surface noise.

I’ve always struggled as to whether Menges of Juan Manén made the first recording of the Beethoven Concerto. Booklet writer Wayne Kiley says Menges, adding that Manén’s recording was made on four sides in 1916 but surely that can’t be right. I make it eight sides – perhaps he’s confused sides with records (Menges takes ten sides). In any case Manén’s recording must have been abridged so let’s give the palm to Menges accompanied by the Royal Albert Hall Orchestra under the typically perspicacious direction of Landon Ronald. This recording has largely been forgotten in favour of the plethora of electrically recorded pre-war sets – Kreisler, Szigeti, Hubermann, Kulenkampff etc. This is a pity as her conception is unobtrusively modern and her execution devoid of intrusive expressive devices but certainly not without a firm sense of characterisation. The orchestra is discreetly bolstered by some reinforcements to allow the bass line to sound and the orchestra is reduced in number from its usual complement – the winds playing without vibrato, the percussion very clear and probably balanced near one of the recording horns. She doesn’t over-broaden for the second subject, unlike many of her contemporaries, and though she does employ portamenti they are never obtrusive. Her bowing is always interesting and her articulation similarly. She plays the Joachim cadenza not the Kreisler. The first side-join is a little tough but thereafter things are fine. The brass reinforcements are most audible in the Larghetto and some of the wind tuning can sound off-putting, largely because of the lack of vibrato, but Menges’ playing itself remains elevated throughout. Her vibrant, creative approach to the finale is focused on rhythm and Ronald sticks to her like glue. No stylistic or expressive excuses need be made for this outstanding interpretation, only the usual qualifications as to acoustic recording.

The second disc starts with two Handel sonatas, one from 1926, the other from 1921-22, both resilient, robust and attractive with Australian-born Eileen Beattie as pianist – one of Solomon’s earliest pupils. Arthur de Greef is the pianist in the 1927 recording of Schubert’s Sonata No.3 offering strong, serious support for her. You’ll find this on the APR set. A series of small pieces follows. The Schubert Ave Maria is expressive without unnecessary dramatics, Hubay’s Der Zephyr is nicely lyric, charmingly phrased and not played as a potboiler. A reminiscence of one of her earlier concerto successes comes in the 1916 recording of the À la Zingara movement from Wieniawski’s Second Concerto which she performed at the time, pairing it with the Beethoven. Here she is accompanied by Charlton Keith, Kreisler’s accompanist for his British concerts. There aren’t many recordings of Stanford’s The Leprechaun’s Dance but whenever I hear one I judge it against Menges’s recording and find all others wanting. Her Elgar is perhaps a touch sentimental and there are a few too many obtrusive finger position changes.

Which leaves The Lark Ascending, the work’s premiere recording, from 1928, with an anonymous orchestra conducted by Malcolm Sargent. It would have been worthwhile for Marie Hall to have recorded this as she gave the first performance, but she hadn’t recorded since the days of the First World War, so Menges was HMV’s logical choice. It will surprise those who long to linger as Menges and Sargent whip through it in 12:38 as opposed to, say, Hugh Bean’s 14:40. Strangely, it doesn’t sound to me to be rushed and generates its own internal rhythm but obviously the limitation in sonics mean it’s more of documentary interest. HMV’s notorious shellac noise has been judiciously tamed.

The fine-sounding discs come from the collection of Raymond Glaspole who is also the transfer engineer, digital mastering being carried out by Rick Torres. This is an important release for violin collectors as Menges’ art, so often taken for granted, was fully worthy of the dedication HMV paid to it and the care Biddulph has shown in restoring it.

Jonathan Woolf

Buying this recording via a link below generates revenue for MWI, which helps the site remain free

Contents

CD1

Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750)

Violin Sonata No.3 in E, BWV1016

Orchestral Suite No.3 in D; Air arr Wilhelmj

Violin Partita No.3 in E: Gavotte arr Kreisler

Violin Sonata No.1 in G minor: Fugue

Violin Partita No.2 in D minor: Chaconne

Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827)

Violin Concerto in D, Op.61

Harold Samuel (piano); Eileen Beattie (piano: Ave Maria, Gavotte)

Royal Albert Hall Orchestra/Landon Ronald (Beethoven)

rec. 1922-29

CD2

George Frideric Handel (1685-1759)

Violin Sonata in A, Op.1 No.13, HWV361

Violin Sonata in D, Op.1 No.13, HWV371

Franz Schubert (1797-1828)

Violin Sonata No.3 in G minor, D408

Ave Maria arr Wilhelmj

Johannes Brahms (1833-1897)

Hungarian Dance No.7 in arr Joachim

Jenő Hubay (1858-1937)

Hejre Kati, Op.32

Der Zephyr, Op.30 No.5

Fryderyk Chopin (1810-1849)

Nocturne in E flat, Op.9 No.2 arr Sarasate

Henryk Wieniawski (18365-1880)

Violin Concerto No.2 in D minor: À la Zingara

Manuel de Falla (1875-1947)

Danse espagnole arr Kreisler

Charles Villiers Stanford (1852-1924)

The Leprechaun’s Dance, Op.89 No.3

Edward Elgar (1857-1934)

Salut d’amour, Op.12

Ralph Vaughan Williams (1872-1958)

The Lark Ascending

Eileen Beattie (piano) except Harold Samuel (piano: Schubert Sonata) and Charlton Keith (piano: de Falla)

Orchestra/Malcolm Sargent (Vaughan Williams)

rec. 1922-30