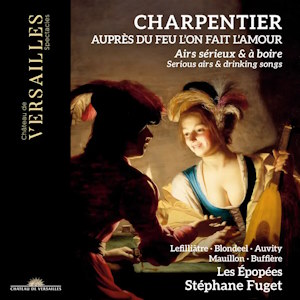

Marc-Antoine Charpentier (1643-1704)

Auprès du feu l’ont fait l’amour – Airs sérieux et à boire

Claire Lefilliâtre, Gwendoline Blondeel (dessus), Cyril Auvity (haute-contre), Marc Mauillon (taille), Geoffroy Buffière (basse)

Les Épopées/Stéphane Fuget

rec. 2022, Salle des Croisades of the Château de Versailles, France

Texts and translations included

Reviewed as a stereo 24/96 download from Outhere

Château de Versailles Spectacles CVS089 [77]

Marc-Antoine Charpentier was not only prolific, but also versatile, contributing to nearly all the genres in vogue in his time. His œuvre includes sacred and secular music, pieces for a large ensemble and works for a single voice, sometimes even without any accompaniment, and also instrumental music. Only keyboard and lute music is absent.

His music is frequently performed. The Te Deum is by far his best-known work, but the discography includes a wide range of compositions. The disc under review comprises pieces that may well be among his least-known works. They are specimens of an important genre in 17th-century France, the air de cour. This term was used for the first time by the music publisher Adrian Le Roy, who, in 1571, published the collection Livre d’air de cours miz sur le luth: songs for voice and lute. He explained that he had adapted simple songs which were known as vaudeville or voix de ville. Until the end of the century various collections of airs de cour were published, but these were all polyphonic. However, they were different from the chansons which were written earlier in that they were simpler, strophic and homophonic. That allowed the text to be more clearly understandable.

In the 17th century, the air de cour developed into one of the main genres of musical entertainment at the French court. Some composers who contributed to this genre are still well-known, such as Puerre Guédron, Antoine Boësset, Etienne Moulinié and Michel Lambert. These airs were mostly scored for a solo voice and lute or basso continuo. Sometimes they included a ritornello for instruments. The texts – always in French – were very different in content: “The range of emotions embraced in these airs involved the serious, depressed, bawdy, high-spirited or even the coquettish (…)”, a commentator writes. That is reflected by the various names given to airs de cour, such as airs sérieux and airs à boire. Some songs include Arcadian elements, represented by shepherds and shepherdesses, which connects them to the Italian chamber cantata which was to become very popular at the end of the 17th century.

The catalogue of Charpentier’s compositions includes about thirty airs de cour, most of which are performed on the present disc. With 76 minutes playing time, there may not have been enough space for the pieces that are omitted here (although technically a disc of 85 minutes is not a problem at all). Never mind; as far as I know, this is the first disc that is entirely devoted to this part of Charpentier’s oeuvre. These songs show a wide variety in content, character and style. Some are typical love songs, often with dark streaks, such as the Stances du Cid. They are included in Le Cid, tragicomedy in five acts by Pierre Corneille, which received its first performance in 1637. Charpentier’s settings were published in 1681 in the newspaper Mercure galant. Corneille was just one of the poets whose texts were set by Charpentier; another one is Jean de La Fontaine. It is a shame that the libretto does not mention the authors of the lyrics.

Some songs are satirical, such as Beaux petits yeux d’écarlate: “Pretty little scarlet eyes, fine full, flat lips, lovely turned-up nose, pretty pointed chin, mane of flaxen hair,weak and scrawny arms, hands drier than Brazil wood. Alas! I shall go to my grave, should my heart, which catches fire like a fuse not be saved from this peril”. It is sung here partly without instrumental accompaniment. It is not entirely clear how it has been preserved. New Grove mentions three voices (SSB); it adds basso continuo with a question mark. Another one is Si Claudine ma voisine, which was originally part of a lost play, L’Inconnu, as is Ne fripez pas mon bavolet. The former is sung by Geoffroy Buffière without accompaniment. Such pieces get a treatment in cabaret style; whether that is in accordance with the performance habits of the time is hard to say. The performers also seem to interpret Celle qui fait tout mon tourment as not too serious a piece, witness the way it is performed. The soprano (the booklet does not say which one) closes the song with increasing speed.

Fenchon, la gentille Fenchon, on the other hand, is undoubtedly not intended as a serious piece: “Fenchon, lovely Fenchon, Fenchon who on Sundays looks so charming, once said, with a voice so grave, looking at her muff: Muff, my poor muff, one need but add a tail the length of a turnip, and you would be mistaken for a poodle.” The fun here is that Charpentier treats it as a really serious piece, with several repetitions, which invite to add ornamentation, as the performers are doing.

Rendez-moi mes plaisirs is an example of a really serious piece, and here we meet Charpentier, the composer who was strongly influenced by the Italian style, as this air is full of pathos: “Give me back my joy, give me my Sylvie, you cruel gods who decide her fate.” Another model of expression is Tristes déserts, sombre retraite: “Mournful wilderness, sombre refuge, rocks to which I have always confided my lot: Listen as I tell you of the secret sorrow, which hastens my death: I loved, I was loved; so happy was my life. Alas! Alas, that time is no more!”

As far as the form is concerned, some consist of just one stanza; in such cases one or several lines may be repeated. Sometimes Charpentier uses the form of the rondeau, ABA, for instance in Allons sous ce vert feuillage. In strophic songs he may use the form of the refrain, such as in Celle qui fait tout mon tourment; each stanza ends with the lines “She who causes all my torment, I love her madly”. Non, non, je ne l’aime plus also has a refrain: “No, no, I love her no more, she withdrew her promise, my bonds are broken.” However, this song is different in that it is separated in recitatives and arias. A repeated bass pattern was popular in France just as much as elsewhere; Charpentier uses it in some of his songs, for instance in Sans frayeur dans ce bois.

Charpentier is rightly considered one of the great masters of the baroque era. His Te Deum is famous for a reason, and his only opera Médée is reckoned among his masterworks. He was undoubtedly a master in setting texts, recognizing their expressive and dramatic possibilities. All these qualities come abundantly to the fore in these miniatures, which mostly take less than three minutes. The performances do them full justice. As I wrote above, how the more satirical or humorous pieces should be performed, is hard to say. I personally feel that these interpretations are a bit too ‘modern’. However, we will probably never know how they were performed in Charpentier’s time. The singers are doing a great job; each one of them is versed in the style of the time, thanks to years of experience in the performance of French baroque music. The fact that they use historical pronunciation cannot be appreciated enough. Unfortunately, that is still not common practice these days.

The booklet includes informative liner notes, which are helpful to understand this repertoire and Charpentier’s contributions to it, as well as all the lyrics with an English translation.

Johan van Veen

www.musica-dei-donum.org

twitter.com/johanvanveen

Buying this recording via a link below generates revenue for MWI, which helps the site remain free

Contents

Auprès du feu l’on fait l’amour (H 446)

Beaux petits yeux d’écarlate (H 448)

Tout renaît, tout fleurit (H 468)

Que Louis par sa vaillance (H 459bis)

Si Claudine ma voisine (H 499b)

Ne fripez pas mon bavolet (H 499a)

Celle qui fait tout mon tourment (H 450)

Ayant bu du vin clairet (H 447)

Rendez-moi mes plaisirs (H 463)

Rentrez, trop indiscrets soupirs (H 464)

Fenchon, la gentille Fenchon (H 454)

Stances du Cid (H 457-459)

Quoi! Rien ne peut vous arrêter (H 462)

À ta haute valeur (H 440)

En vain, rivaux assidus (H 452)

Ruisseau qui nourrit dans ce bois (H 466)

Feuillages verts, naissez (H 449a)

Oiseaux de ces bocages (H 456)

Tristes déserts, sombre retraite (H 469)

Consolez-vous, chers enfants de Bacchus (H 451)

Au bord d’une fontaine (H 443bis)

Allons sous ce vert feuillage (H 444)

Sans frayeur dans ce bois (H 467)

Il n’est point de plaisir véritable (H deest)

Non, non, je ne l’aime plus (H 455)

Ah! Laissez-moi rêver (H 441)

Veux-tu, compère Grégoire (H 470)

Ah! Qu’on est malheureux d’avoir eu des désirs (H 443)

Il faut aimer, c’est un mal nécessaire (H 454bis)