Ralph Vaughan Williams (1872-1958)

Flourish for Glorious John (1957)

Fantasia for piano and orchestra (1896-1902, rev. 1904)

The Steersman (1906, realised and orchestrated by Martin Yates, 2022)

The Future (ca 1908, completed and orchestrated by Martin Yates, 2019)

Lucy Crowe (soprano); Jacques Imbrailo (baritone)

Andrew von Oeyen (piano)

BBC Symphony Chorus & Orchestra/Martin Yates

rec. 2022, St. Jude-on-the-Hill, Hampstead Garden Suburb, London

Texts included

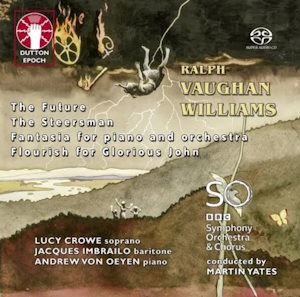

Dutton Epoch CDLX 7411 SACD [67]

This is a release which will be of great interest to all VW devotees, containing as it does first recordings of two early scores, The Steersman and The Future which were left incomplete by the composer and which have been prepared for performance by Martin Yates. Hugh Cobbe’s notes provide valuable background on all the compositions and I’ve drawn on them in the course of this review.

Before considering those two works, however, one should not overlook the other two items on the programme. Flourish for Glorious John was composed as a present for VW’s great friend and long-time champion, Sir John Barbirolli. It was written to open the concert in October 1957 at which Barbirolli and the Hallé began the orchestra’s centenary season. The piece is just 59 bars long and here plays for 3:05 but it seems more substantial than that. It’s scored for a large orchestra, with the addition of both piano and organ. It’s a rather splendid pièce d’occasion which Martin Yates and the BBCSO make into an exciting, opulent-sounding programme opener.

From one of VW’s very last compositions, we move to something from much earlier in his career: the Fantasia for piano and orchestra. He worked on it between 1896 and 1902 and made some revisions in 1904. Hugh Cobbe speculates, plausibly, I think, that the revision might have been occasioned by the prospect of a performance, but he tells us that there is no record that the piece was actually played in VW’s lifetime. It remained unpublished until relatively recently when Ursula Vaughan Williams agreed that some of her husband’s unpublished early works could be released. Graham Parlett edited it and the work was given a first recording in 2010 by Mark Bebbington (review). Hugh Cobbe states that the present recording is the second, but I don’t think that’s quite right; Sina Kloke recorded it in 2015 with the Chamber Orchestra of New York conducted by Salvatore Di Vittorio (review). For some reason, I missed both of those discs so this new recording by Andrew von Oeyen has been my introduction to the piece.

The Fantasia is no musical shrinking violet. The music is confident – and confidently scored – and the piece is substantial; this performance plays for 20:25. Near the start (1:03) the orchestra plays a rather serious and impressive chorale-like theme; this proves to be the thematic cornerstone of the work. The melody is noble and, hearing it, I’m very glad that Ursula allowed this piece to be among the early pieces released to public scrutiny. In the following pages both the pianist and the orchestra elaborate on this theme to good effect. Eventually (at 13:30), after a quasi-cadenza based on the main theme, the soloist launches an energetic episode in 12/8 time. This is athletic and extrovert; there’s quite a lot of brilliance in the writing for the piano. The piece reaches its big moment with a grand reprise of the chorale, played sonorously by the orchestra (17:36); this is followed by a cadenza. The conclusion of the piece is unusual and comes as something of a surprise. The orchestra marks the end of the cadenza with a fortissimo statement, after which the volume fades almost to nothing. Just when you think the Fantasia will end in a subdued vein, there’s a crescendo roll on the timpani, leading to a loud sec chord on which the piece takes its leave.

I liked the Fantasia very much and I also enjoyed the present performance. The music may not contain many – if any – hints of VW’s mature style but the piece gives us a fascinating glimpse of his compositional and stylistic development at the turn of the twentieth century; more than that, it’s well worth hearing in its own right. In his notes, Hugh Cobbe suggests that “the style owes something to Brahms and Rachmaninov”. I take that point and the brilliant piano writing is suggestive of the Russian master (though quite how much exposure VW would have had to Rachmaninov’s music by that point in his life I’m unsure). However, I think the German influences are more pronounced; this should not surprise us because German music was a prevalent influence on nineteenth century British music. Also, I’m reminded that VW travelled to Berlin in late 1897 and during his time there he studied with Max Bruch. Whatever the influences, the Fantasia is a piece that I’m glad I have discovered; Andrew von Oeyen and Martin Yates make a strong case for it.

The rest of the disc contains two premiere recordings of scores which Martin Yates has realised/completed and orchestrated.

The Steersman is a setting of a Walt Whitman poem. The poem in question is ‘Aboard at a Ship’s Helm’ (published in 1867) which, it seems, VW contemplated including in A Sea Symphony; it would have been in addition to the four movements with which we are so familiar and would have been placed fourth, between the Scherzo ‘The Waves’ and the extended finale, ‘The Explorers’. The setting is for baritone and orchestra, in addition to which a female chorus is deployed near the end.

The present performance lasts for 9:57. The kinship with A Sea Symphony is established almost immediately; at 0:23 a solo bassoon plays the melody from the early tone poem The Solent (1903) which crops up in the symphony too. In fact, this is the first of several references to the melody during the course of The Steersman. VW’s setting of Whitman’s lines is mostly nocturnal and mysterious, though there’s a powerful passage in the section which begins with the words ‘The bows turn…’ At 7:43 the bright timbre of female voices is heard as the ladies sing the last two lines, beginning at ‘But O the ship, the immortal ship!’ The end is interesting. The baritone soloist sings the word ‘voyaging’ three times before the final hushed bars are played by the orchestra; the atmospheric (though not thematic) similarity with the conclusion of A Sea Symphony is palpable.

VW abandoned The Steersman, though I’m not entirely sure how much completion work, in addition to orchestration, was required to bring it to performance. Hugh Cobbe says in his notes that “there was sufficient material in [VW’s] score for Martin Yates to orchestrate it and be confident that the composer’s intentions were reflected in the result”. Cobbe goes on to say something with which I very strongly agree: “it is clear that on stylistic grounds it would be a great mistake to go against the composer’s own decision and perform The Steersman as part of the symphony from which it was excluded”. That’s a point very well made, not least because, as Cobbe points out elsewhere, the harmonic language in this setting differs from what we hear elsewhere in the symphony. But I think another point is worth making. Any thought of including The Steersman as the fourth movement of A Sea Symphony would completely undermine the structure of the four-movement work that VW left us. One of the most telling gestures in A Sea Symphony is the way that the brilliance of ‘The Waves’ gives way to the mysterious, expansive opening of ‘The Explorers’. Interpolate The Steersman between those two movements and you completely lose that effect. No, The Steersman must be left as a standalone curiosity, worth hearing as a point of interest in VW’s artistic development, but not more than that.

The music is well served by this performance. Yates obtains atmospheric, sensitive playing from the BBCSO; his scoring is effective, I think. The ladies of the BBC Symphony Chorus make an excellent, if brief, contribution. Jacques Imbrailo sings the solo part very well.

The most substantial score here is The Future. This is a setting of Matthew Arnold’s poem, published in 1852. As Hugh Cobbe tells us in his notes, Michael Kennedy believed that VW was working on this setting in about 1908, so it is roughly contemporaneous with Toward the Unknown Region and A Sea Symphony. VW did not complete the work; what is left is a notebook comprising 32 pages, which is kept in the British Library. I’ve been able to see the manuscript. The surviving setting ends at the point where VW set the lines ‘Denser the trade on its stream / Flatter the plain where it flows’. That’s roughly about halfway through Martin Yates’ realisation. How far VW progressed beyond that point I don’t know but it seems likely that there was more music but that this has been lost. The music that VW left behind is very much a sketch, with only very occasional indications of how he might orchestrate it. Though the vocal lines are written out, there are bars where the harmony is missing. As you’ll gather, a considerable amount of intuition and experience of VW’s music was required to bring the piece into a performable state. Inevitably, quite a bit of conjecture will have been involved and Hugh Cobbe includes a lengthy comment by Yates in which he details some of the principles by which he worked: in particular, Yates intuited that the fact that VW used the term ‘rep’ (reprise?) in various places meant that he intended to revisit the music in question later in the piece; that seems a reasonable assumption.

The result of all Yates’ work is a single-movement setting which here plays for 33:01: thus, it’s a few minutes longer than the last movement of A Sea Symphony. Partly, that’s due to the length of Arnold’s poem; the text, as printed in Dutton’s booklet, runs to some 70 lines, and that’s after VW omitted a couple of stanzas! I found the piece very interesting to hear and I was convinced by much of what Martin Yates has done, not least in terms of the orchestration. I do wonder, though, whether, had VW completed the score and seen it through to publication/performance, he might have made it tauter. In particular, there’s a great deal of music that is slow-paced and expansive; what we hear is often beautiful but I wonder if a score completed by VW would have been shorter – and beneficially so. Having initially disregarded two stanzas of the poem, perhaps, on reflection, he might have made cuts and set even less of what is a substantial and complex poem. (In support of this conjecture I would cite the fact that, as I mentioned earlier, he thought about making A Sea Symphony even longer by including a fifth movement but, wisely, thought the better of it.)

As I said, I admire Martin Yates’ work on this score but I was left somewhat dissatisfied by the way in which he brings The Future to an end. At 27:49 the soloist introduces the last five lines of the poem, singing ‘As the pale waste widens around him…’ This and the words that follow invite tranquil, beautiful music and that’s precisely what Yates provides. Lucy Crowe sings this music with great feeling and when she’s joined by the chorus the mood and music are of a piece with the opening pages of Toward the Unknown Region and several episodes in A Sea Symphony. Just one brief orchestral climax interrupts the tranquil atmosphere. Then, at 31:07 a processional passage for chorus and orchestra begins. Gradually, it builds to a very strong, emphatic conclusion. It works – in a way – but the last line of the poem is ‘Murmurs and scents of the infinite sea’. I can’t help feeling that had Yates maintained the glowing tranquillity to the very end, The Future would have achieved a much more satisfactory conclusion.

However, that’s a personal reaction and others may form a different view. Martin Yates’ completion of The Future opens, fascinatingly, a window which allows us to glimpse what else was occupying VW’s creative mind during the period when he was bringing Toward the Unknown Region and A Sea Symphony into being. The Future contains a lot of beautiful and imaginative music and the score is well worth hearing. The first performances of The Future were given in Edinburgh and Glasgow in November 2019 when Yates conducted Ilona Domnich (soprano), the Royal Scottish National Orchestra and the RSNO Chorus. I don’t know if any other performances have taken place since then but this recording will be invaluable in bringing the music to a much wider audience. The present performance is excellent. Lucy Crowe is a fine, expressive soloist and the BBC Symphony Chorus sing very well. My only criticism of the choir is that even when listening through headphones I didn’t always find it easy to hear the words clearly, especially when the music is loud. The BBC Symphony Orchestra plays the score very convincingly under Martin Yates’ direction.

The recorded sound is very good indeed and Dutton have provided good documentation.

This is a disc which sheds fresh light on Vaughan Williams’ composing activities around the turn of the twentieth century. As such, it will be of considerable interest to anyone interested in the music of this great composer.

John Quinn

Buying this recording via a link below generates revenue for MWI, which helps the site remain free