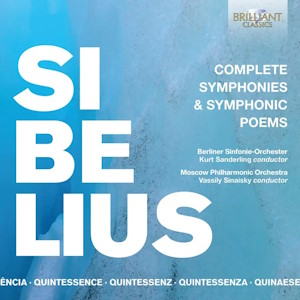

Jean Sibelius (1865-1957)

Complete Symphonies & Symphonic Poems

Berliner Sinfonie-Orchester /Kurt Sanderling

rec. 1970-77, Christuskirche, Berlin ADD

Brilliant Classics 96113 [5 CDs: 347]

Rob Barnett first favourably reviewed Sanderling’s 1970 recordings of Sibelius’ symphonies on the Berlin Classics set issued in 1996 with Night Ride and Sunrise, Finlandia and En Saga, in four CDs; he revisited them two years later (review) when Brilliant Classics issued their own five CD box, adding fifteen minutes’ more music with a Valse Triste from Sanderling and an orphaned Swan of Tuonela conducted by Paavo Berglund with the Berlin Radio Symphony Orchestra. This review of the latter set (see footnote), a quarter of a century on and prompted by discussion on the MusicWeb Message Board of the comparative merits of various box sets of Sibelius symphonies is an exercise perhaps validated by the continued relevance of RB’s remark that Sanderling’s work does not receive the attention it deserves.

First, the sound: RB detected no difference between the Berlin and Brilliant sets; there is some slight hiss from the magnetic tape analogue recordings which are otherwise of excellent quality. That sound is very good; there is also some faint underlying rumble but neither extraneous sound at both ends of the spectrum is disturbing and in any case, discernible only on headphones. Nonetheless, there is no sense in which it rivals the digital clarity and immediacy of the sound Decca gave Klaus Mäkelä in his recent complete set of symphonies.

The raw energy of Sanderling’s attack in the opening movement of the First Symphony is compelling and the soundworld he generates is wholly idiomatic: lean, a little raw and abrasive – no hint of undue plushness. However, that spareness isn’t overdone; there is plenty of Romantic ardour and indulgence in the reprise of the Big Tune around 7:45. I find the second movement to be a bit spasmodic and disjointed, albeit very well played but the Scherzo is thrilling, graced by some excellent horn-playing and nicely prominent timpani. The fast sections of the finale are very clipped and angular, and their celerity might be too much for some but the alternate slow passages are contrastingly caressed and the concluding grand melody is really heroic.

Everything about the start of the Second is right – pointed rhythms, plangent, nasal woodwind, but I find the tempo a little deliberate in the central section. The second movement, too, is strangely flat and tensionless; Sanderling lets the whole thing go limp and it flounders. I never expected to be bored by his conducting but here…The Scherzo is better but I have heard more sharply articulated accounts and the Trio is again somewhat lacklustre and the launching into the famous finale is not the most voluptuous I know. As a whole, Sanderling’s manner with this symphony is simply too casual and restrained; around five minutes in, it loses all momentum and just noodles on; the supposed climax at seven minutes goes for nought. I don’t know what went wrong here but this is dull.

Likewise, I look for more vigour in the bustling semiquavers of the opening of the Third and Sanderling’s ritardando three minutes in is excessive but the jolly folk tune six minutes in is much more vivacious and blooms into an expansive ending. The Andantino is captivating and the finale makes its mark.

I have only recently come to a proper appreciation of Sibelius’ Fourth Symphony and I like the buzzing sonority of the Berlin strings here in service of Sanderling’s stealthy pacing. The music expands impressively at four minutes in, the brass, strings and timpani opening up sombre vistas – but again, I feel that Sanderling’s grip loosens after that. The second movement Allegro molto vivace is tighter and steadier – as I like it: uncompromising. The slow movement is broodily mysterious and the finale builds persuasively in a carefully and even cunningly controlled fashion over a long arc of ten minutes from a kind of manic gaiety through courageous posturing into resignation and despondency.

I do not derive much sense of occasion from the horn and woodwind announcements opening this Fifth but the development around two and a half minutes in which recalls swinging bells and the subsequent tremolo section for strings are much more engaging. The bassoon solo beginning at seven minutes is haunting and the advent and gradual acceleration of the swinging dance tune two minutes are captivating; that gradual, almost imperceptible, upping of the pace is skilfully managed and culminates in an explosive conclusion. The triple-time middle movement oozes rustic charm and Sanderling seems to emphasise its kinship with Mahler’s soundworld. The bustling finale is a tour de force, featuring wonderfully crisp playing and – of course – suitably grandiloquent horns; the famous gapped conclusion is daringly etiolated.

The Sixth opens in marvellously poised, plangent and plaintive manner – lovely playing from the flutes and strings before what RB rightly calls “the motoric propulsion” of the joyous main theme; I cannot imagine this better executed. The gentle, wistful slow movement unfolds engagingly, gradually revealing a mysterious, even mildly menacing dimension, reminiscent at times of Wagner’s Forest Murmurs. The Scherzo flits by, light as air and the finale glows, suffused with bucolic vitality and concludes enigmatically. This is in many ways the best performed symphony in this collection.

The Seventh is a tricky one to pull off, both in itself and in terms of outfacing established competition. I think Sanderling simply miscalculates here and I quote RB again, as he identifies the problem: “Sanderling’s propensity for caressing detail robs the music of its essential tension.” It is indeed slack and nerveless where it should be tugging forward, constantly yearning to break free rather than dawdling; for all its incidental beauties – such as the brass “sunrise” five and half minutes in – it just does not work. Like the Second Symphony, it never quite takes off – although the faster central section before the trombone solo is more successful. The lyricism is there but not the inner drive and the exaggerated rallentando before the final brass chorale is clumsy, as are the come scritto concluding bars – no Ormandy-style tinkering here – which are too heavy and devoid of fantasy.

While it is always good to have the compilation of tone poems such as fill the final disc, to some extent their quality becomes irrelevant if the main offering of the corpus of symphonies is deficient. As it happens, there are some good, if not outstanding, versions here; RB details some flaws in his review but also praises especially successful items such as Sanderling’s Night Ride and Sunrise – which is not, however, among his masterpieces. The Finlandia is a bit crude and un-nuanced, very “in-yer-face”. En Saga is precisely executed and its depiction of seas, horseback rides and mountains is highly atmospheric – though again, I do not think it is one of Sibelius’ most striking works.

The performances of the Second and Seventh Symphonies here are for me two comparative interpretative failures; as such, I cannot admit this set into my pantheon of great Sibelius recordings.

Ralph Moore

Buying this recording via a link below generates revenue for MWI, which helps the site remain free

Footnote

The intention of this review was to evaluate Sanderling’s symphony cycle, and I used the Brilliant Classics boxset referred to Rob Barnett: catalogue number 6899. That has become unavailable, and has been reissued twice by Brilliant Classics with different couplings. The sales link is to the most recent issue. Therefore, no comment is made regarding the Sinaisky recordings.

Contents

Symphony No. 1 (rec Jan 1976)

Symphony No. 2 (rec Sept 1974)

Symphony No. 3 (rec Nov 1970)

Symphony No. 4 (rec May 1977)

Symphony No. 5 (rec Dec 1971)

Symphony No. 6 (rec Jan/Feb 1974)

Symphony No. 7 (rec Jan/Feb 1974)

Finlandia (rec. Dec 1971)

Night Ride and Sunrise (rec. May/June 1977)

En Saga (rec. Nov 1970)

Lemminkäinen Suite, Op. 22

Tapiola, Op. 112

Moscow Philharmonic Orchestra/Vassily Sinaisky