Déjà Review: this review was first published in May 2005 and the recording is still available.

Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750)

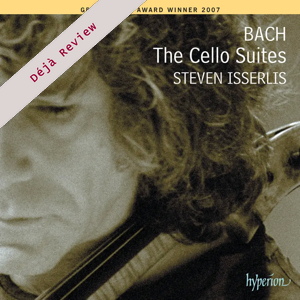

The Cello Suites

Cello Suites Nos 1-6

The Song of the Birds (arr. Sally Beamish)

Prelude from Cello Suite No.1 (Anna Magdalena manuscript)

Prelude from Cello Suite No.1 (Johann Peter Kellner manuscript)

Prelude from Cello Suite No.1 (Johann Christoph Westphal collection)

Steven Isserlis (cello)

rec. 2005/06, Henry Wood Hall, London

Hyperion CDA67541/2 [2 CDs: 137]

There is no such thing as a definitive performance or recording of J.S. Bach’s six suites for cello solo. The origins of the works are shrouded in enigmatic mystery so there is not even an urtext edition although as this recording’s extra tracks illustrate there are numerous sources, each of which has its own fascinating insights and validity. Historians have concluded that the works were written some time around 1720, or at the very least during Bach’s time as Kapellmeister of the court orchestra of Prince Leopold of Anhalt-Cöthen, when he had no choir or responsibility for church music but did have a virtuoso instrumental ensemble, for whom among other works the Brandenburg concertos were written.

Like all of Bach’s solo work, the beauty for the listener is not only in superbly constructed musical forms, seamlessly perfected counterpoint and elegantly expressive melodic lines. Each performance is also a communion of the musician with Bach’s music through the medium of their instrument, reflecting the artist’s feelings, and surprisingly often on how they feel on that day or in that moment. With the suites for cello we are also given the gift of that most natural of instruments, whose range finds close correspondence to the human voice and is therefore – in the right hands – a most amenable and communicable sound for extended listening. Viewed from all angles, this is such a personal medium I find it impossible to make this much in the way of a comparative review. I brought out my copy of the 1983 CBS recording by Yo-Yo Ma just as a point of reference, as well as a dusty old box of the 1964 Philips recordings by Maurice Gendron. Readers will no doubt have their own favourites, and no new recording is likely to persuade anyone to part with their Tortelier, Rostropovich, Casals or Fournier; neither should they. Each is the individual statement of a great artist, and personal taste will already have had you gravitating more often to one over the other.

So, what is to be gained with this new Hyperion set by that great star in the string firmament Steven Isserlis? If you happen to make an A-B comparison, you may at first be surprised by the relatively small-scale approach. Used to big-boned and fairly romantic interpretations by the likes of Ma and Casals, Isserlis sounds relatively intimate, not really introvert, but somehow sourcing the foundations of his expressiveness from a different place. If however you have been sensible, and not put this new recording up against a golden oldie, then there need be no question about any sense of scale or proportion. Isserlis’s playing is deft and light, the music rendered direct and transparent. Even before reading the booklet notes, you should feel you are being engaged by a very vocal, almost conversational discourse. The playing doesn’t hector or lecture, but welcomes the listener into a richly verdant field of ideas and musical allegories. Isserlis presents the music not so much as technically virtuosic and compositionally brilliant – such aspects are incidental: he is communicating a narrative.

Isserlis’s own booklet notes reveal the great deal of time and effort which has gone into choosing the best options when it comes to the available sources for this music. The results have produced four versions of the Prelude to the Suite No.1 in G, whose differences are rather more in the detail than in the substance. True, different slurring changes the lines and different notes pop through here and there, but the exercise, while having its own fascinations, is something of an academic one. Somewhat perversely Isserlis leaves in obvious copying errors, which on occasion had this reviewer thinking that the editing had gone wrong. Never mind, these make for interesting bonus tracks, and show something of how the ideal world of the final versions was arrived at. The pleasantly arranged Catalan folksong The Song of the Birds is also a nice extra, serving to break the intensity of the last moments of the Suite No.6, and throwing Bach’s incredible genius into even sharper light.

The playing is, in my opinion, a delight and an inspiration throughout. As previously mentioned his is a light touch, and so even the most intense passages never sound like the kind of scrubbing which has sometimes put me off the cello in the past. He can dig deep and the dynamic range is tremendous: but even the most dramatic moments have a grace and poise which I find irresistible. His tempi are never abnormally extreme, and while he is brisk and efficient in the dances there is plenty of time for ecstatic expression where the music demands. One of the things I enjoy most is the natural sense of flow, which makes the music seem timeless; both ancient and freshly-minted at the same time. There is rubato, but you don’t experience it as rubato, you experience it as music in the purest sense of the word. In this, Isserlis’s control is absolute. Take the elastic way in which time undulates in the Menuets I and II of the Suite No.1. At each repeat, the quasi-silence between phrases has its own special expressive power – you don’t sense it as a round of repeats, more a circular object studded with jewels of infinite variety.

At the end of his booklet notes, Isserlis provides us with his personal feelings on the suites, amounting to a kind of ‘confessional’ of the way he has come to see them as ‘Mystery Suites’ in the sense of the three kinds of ‘Sacred Mystery’: Joyful, Sorrowful and Glorious. Isserlis makes no attempt to turn this into a scholarly interpretation of Bach’s original intentions, and freely admits that such a reading is impossible to prove as authentic, although to his mind it fits the works exactly. Some of his descriptions of the individual suites may seem a bit far-fetched, but what does result is a line through which all of the suites are given a satisfying continuity. There are no clear favourites or highlights, as each work has its own function and expressive power. The musical journey on which you are taken is something like being presented with the St. Matthew Passion on a single instrument – something you might have thought impossible to re-create, but in the presence of this recording, something I find equally impossible to deny.

The Henry Wood Hall is an ideal acoustic, and Hyperion’s recording is quite remarkable. You can play it at distance, softly and candlelit. Turn up the volume and Isserlis comes closer and closer, until you are as good as inside the gorgeous Feuerman Stradivarius instrument, bouncing around with the little ball of mousy fluff at the bottom in the most deeply resonant bits. As a set of the complete cello suites by J.S. Bach this, to me, represents the best of the best in this most personal of all possible worlds.

Dominy Clements

Buying this recording via a link below generates revenue for MWI, which helps the site remain free.