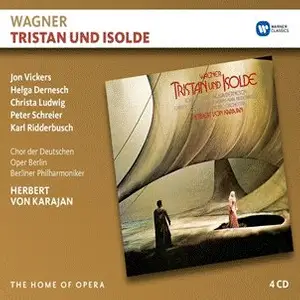

Richard Wagner (1813-1883)

Tristan und Isolde (1865)

Tristan: Jon Vickers (tenor)

Isolde: Helga Dernesch (soprano)

König Marke: Karl Ridderbusch (bass)

Kurwenal: Walter Berry (baritone)

Brangäne: Christa Ludwig (mezzo)

Melot: Bernd Weikl (baritone)

Sailor/Shepherd: Peter Schreier (tenor)

Helmsman: Martin Vantin (baritone)

Chorus of the Deutsche Oper Berlin

Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra/Herbert von Karajan

rec. 1971/72, Jesus Christus Kirche, Berlin-Dahlem

Warner Classics 2564695947 [4 CDs: 229]

Herbert von Karajan’s recording of Tristan und Isolde has been something of an also-ran in the Tristan steeplechase since it first appeared in 1973. The fact that a meticulously planned recording, which featured a cast of some of the finest singers of the late 20th Century could turn into such a disappointment is a cause for depression. The blame for this rests securely on the shoulders of the conductor and his recording producer Michel Glotz.

Herbert von Karajan’s micro-managing style of conducting was something that often came under critical fire during the 1970s and 80s. Sometimes it could pay dividends as it did in parts of his Ring Cycle for DG and the second recording of Die Meistersinger for EMI. However, more often than not his obsessive quest for perfections of sonic beauty and his unusual preoccupation with dynamic levels led to some weird and downright distasteful, opera recordings such as the 1979 Le Nozze di Figaro (Decca)and Pelléas et Mélisande (EMI).

In Tristan he works hard to achieve a sonic purity that unfolds seamlessly out of the ravishing playing of the Berlin Philharmonic. The problem is that Tristan is much more than that just a beautiful objet d‘art; it expresses an equal mix of pain and pleasure with passion and a very real sense of longing. As one listens to von Karajan’s interpretation it become apparent that he was transfixed by the beauties of Wagner’s score to the point of overriding everything else. What he has created is the operatic equivalent to a Fabergé egg: a finely –crafted thing of immense beauty but also something which is unable to inspire any sort of emotional response.

Helga Dernesch is an Isolde with an uncommonly warm and sensual sound in her middle and lower registers which gives her Isolde a very feminine sound. Although she was promoted as a dramatic soprano she was really a mezzo with a strong upper voice. On this recording her upper register is beginning to sound tired and strained; certainly the warmth of her sound begins to disappear at around upper “G”. Some of Isolde’s higher passages emerge with clarity, but more often than not the sense of strain produces a waspish sound where vocal brilliance is called for.

Jon Vickers’ truly heroic-sounding tenor has a strong personality within his tone, not to mention the trumpet that is buried somewhere in those vocal cords. His Tristan is one of the most memorable on any recording; there is strength and dignity of bearing in both the sound, and his approach to the role. Vickers is the one singer in this cast whose vocal personality is strong enough to be a match for von Karajan’s micro control, which makes the listener’s encounter with Tristan’s Third Act ravings an often moving experience.

Christa Ludwig’s Brangäne is securely and sensitively sung. She and Dernesch easily sound as if they could be sisters. Ludwig is wonderfully expressive when she warns Isolde about Melot’s plotting, and even better in the solo from the watchtower. Her vocal excellence leads one to think she could easily have sung Isolde in place of Dernesch; certainly her recording of the Liebestod for Otto Klemperer proves that she had the ability to sing a superb Isolde, on records if not on the stage.

Walter Berry finds Kurwenal’s range a bit of a stretch for his voice. Occasionally he sounds rough in some declamatory passages, however his portrayal of the rugged but devoted retainer is completely winning and even the patches of strain contribute to the overall picture of a man who gives his life to protect his master.

Karl Ridderbusch’s King Marke is sung with great beauty of tone and noble bearing. He joins a regal assortment of other outstanding Cornish Kings including Kurt Moll, Martti Talvela, and Matti Salminen on rival recordings. In the smaller roles a young Bernd Weikl reveals a voice of great beauty and thrust as Melot, and Peter Schreier’s elegiac airy sound is deluxe casting for the offstage sailor and the shepherd.

The other challenge of listening to this set lies in the engineering department. The orchestra is often encountered at a distance in the sound field which leaves it sounding rather diffused more often than not; suddenly the focus will shift and the instruments are up close and risk drowning out the singers. Singers too will be present one minute and then far away the next. Volume levels are also constantly shifting; for example the Act Three Prelude has the orchestra playing so quietly that it is difficult to hear them even with a volume increase, then suddenly the English horn solo registers up close. In another example Brangäne is placed at an extreme distance for her watch (beautifully sung by Ludwig) but she is too far away for her words to register with even a minimum of clarity.

One can easily be entranced by the beauty of the orchestral sound that Karajan achieved here, but that is only half the picture of Tristan und Isolde. In an opera lasting four hours beauty of the sound can only hold the listener’s attention for so long before boredom starts to creep in. That was the main problem with von Karajan’s recording of Pelléas et Mélisande, sheer beauty at the expense of the dramatic. Here Karajan achieves the same mixed result. One wants deeply to love this recording because of the strength and imagination of the cast, but reluctantly it gets filed away on the shelf because it has to take a back seat to other versions, the ones which give a more complete picture of Wagner’s most harrowing music drama. Listening to Leonard Bernstein’s, Karl Böhm’s, Carlos Kleiber’s or Daniel Barenboim’s recordings all provide the listener with much greater emotional impact no matter what their feelings are towards the respective casts. This recording is proof that a standout lineup of singers is not enough on its own to make a rewarding Tristan.

Mike Parr

For another view of Karajan’s Tristan und Isolde, please see Ralph Moore’s survey, in which he places it among his first choices.

Help us financially by purchasing from