Richard Strauss (1864-1949)

Four Last Songs

Orchestral and Piano Versions

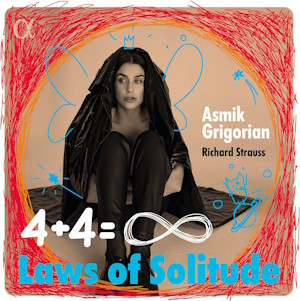

Asmik Grigorian (soprano)

Orchestre Philharmonique de Radio France/Mikko Franck

Markus Hinterhäuser (piano)

rec. 2022, Auditorium de Radio France, Paris (orchestral); 2023, Herkulessaal, Munich (piano)

German texts and English & French translations included

Alpha Classics 1046 [44]

I first encountered the Lithuanian soprano, Asmik Grigorian a few years ago through her astonishing assumption of the title role in Salome (review). Now, she has recorded, under studio conditions, another of Strauss’s great gifts to the soprano voice, his Vier letzte Lieder. We should never forget that it was not Strauss himself who bestowed on these four songs the title, Vier letzte Lieder. In something of a parallel with Schubert’s Schwanengesang, the songs were grouped together under that title by Strauss’s friend Ernst Roth, prior to publication. (There was, of course, one more song, Malven, which was written after these, later in 1949 and which was truly the composer’s Last Song.)

I have literally lost count of the number of recordings of these wonderful songs that I have in my collection. However, without exception these are recordings of the version with orchestral accompaniment in which they are so justly celebrated. Here, Asmik Grigorian has done something refreshing and rather interesting in pairing that familiar orchestral version with one in which the singer is accompanied by piano. I’m sure I don’t have a recording of the songs with piano accompaniment; indeed, I’m not sure I’ve previously heard them performed in this way. I note that according to the MusicWeb International Masterworks Index, we have published reviews of 37 different recordings; all of them are with orchestra.

In his booklet note, Nicholas Derny states unequivocally that the Vier letzte Lieder “were published posthumously in two versions by Boosey & Hawkes: one with orchestra, the other piano accompaniment”. I was slightly surprised to see in the track list that three of the songs are credited as “arranged by Max Woolf” while ‘Im Abendrot’ is “arranged by John Gribben”. I was able to check this point with a pianist who has performed the piano version in public and I learned that these arrangers are credited in the Boosey & Hawkes piano score. From this I conclude that some editing/arranging work was needed in order to prepare Strauss’s music for publication with piano accompaniment; I have no idea how extensive the work had to be.

In the booklet there’s a brief introduction by Ms Grigorian in which she says this: “My main interest in recording both versions…was that they each require different colors (sic) – even if they are the same piece”. I presume she is referring to vocal colouring because the most obvious difference is that the piano version can’t hope to replicate the range of colours that we experience when listening to the orchestral version. However, there’s even more to it than that: we don’t hear two identical vocal interpretations with different accompaniments; as we shall see, Ms Grigorian approaches the songs differently in both performances and most definitely employs a different range of vocal colours.

Obviously, when listening to the disc one would listen straight through to either the orchestral or the piano versions, but on one occasion I found it instructive to listen to each song consecutively in both versions – listening to the piano version second – and that’s how I’ll approach the task of writing this review. First, though, a few general points. Firstly, Asmik Grigorian sings the songs beautifully – but differently – and with great accomplishment and understanding on each occasion. Secondly, the orchestral accompaniment is excellent during the familiar version. Thirdly – and this is a key point – there will be occasions in the comments that follow when I will express a preference for the orchestral version. Such a preference refers only to the version; it is not intended as an adverse reflection on the sensitive and very fine pianism of Markus Hinterhäuser. Finally, prior to playing the disc I had assumed that if there were tempo differences between the two performances, I’d find that the orchestral version was the broader of the two simply on account of the greater sustaining capabilities of an orchestra over the piano; rather to my surprise, the opposite was true.

In ‘Frühling’ I like the excellent flow which Mikko Franck imparts to the music. He encourages the Orchestre Philharmonique de Radio France (OPRF) to play in a way that I’d describe as sumptuous but light. Grigorian’s voice soars in a most attractive way. This is an auspicious start to the orchestral version. In the piano version, the singing is also lovely though, oddly, I found that the words were less easy to discern that in the orchestral performance – not something that was an issue elsewhere in the piano performance. The trouble is that one can’t escape the fact that the accompaniment is being provided by a percussive instrument. For all the skill of Markus Hinterhäuser he can’t convey the gossamer subtleties that we find in Strauss’s orchestral palette; the piano part is too ‘present’. Perhaps the cruellest comparison comes when we hear the instrumental postlude; the placing and voicing of the chords right at the end is not as subtle as is the case in the orchestral version while on the piano the last bass note is rather more solid and emphatic than the double bass pizzicato. But, I emphasise again, the foregoing is no criticism of Hinterhäuser’s playing per se; and, as we shall see, it’s premature to dismiss the piano version after one song.

The first real revelation comes with ‘September’. In the orchestral version the soft-hued strings and woodwind of the OPRF are delightful; once again, Franck keeps the music persuasively on the move, investing the song with fluidity. The golden-toned horn solo at the start of the postlude is very pleasing. Grigorian sings the song with feeling, her voice beautifully produced. However, in the piano version, she and Hinterhäuser offer a very different, rather darker conception of the song. I wonder if they have taken their cue from the very first line of Hermann Hesse’s poem, ‘Der Garten truaert’ (‘The garden mourns’). The tempo is noticeably broader than the one set by Mikko Franck – the piano performance lasts for 5:59, the orchestral version for 4:04. Grigorian and Hinterhäuser take a fascinatingly different view of the song as compared with her account of it with orchestra. She spins a gorgeous line throughout and her last phrases (‘Langsam tut er die großen / müdgewordnen [Augen] zu’) are sung with real feeling. Indeed, I have the sense that since the very start of the song Grigorian and her partner have had their eye on the word ‘Langsam’. Hinterhäuser maintains the slow pulse, of course, throughout the postlude. I miss the orchestral colouring, not least the wonderful horn solo. Intriguingly, though, this passage offers one of many examples throughout all four songs where the piano version clarifies the harmonies; here, it’s the dissonance at the end of what is the horn’s first phrase in the orchestral version (at 4:54, or at 3:20 in the orchestral performance). As I say, Grigorian and Hinterhäuser present a very different – and perfectly valid – conception of the song in the piano version. I think I’d liken it thus: in the orchestral performance I have the impression of the month of September presented in the gentle, mellow lights of late summer; in the piano performance the darker hues of impending autumn are to the fore and, indeed, the performance seems to remind us that autumn will presage winter.

‘Beim Schlafengehen’ is my favourite among this quartet of songs. Above all, I love the passage where the tender violin solo leads us into the rapturous third stanza. Here, the violin solo is beautifully played (from 1:43), the ebb and flow of rubato expertly judged by both the violinist and the conductor. When Grigorian sings again (‘Und die Seele unbewacht / will in freien Flügen schweben’) the text speaks of the soul soaring and that’s just what her voice does. She spins the decorated vocal line ecstatically and after she has finished singing Franck and the OPRF impart a golden glow to the postlude. When one turns to the piano version the pace is slower – but only marginally so – and the colours from both pianist and singer have a darker hue. I mean no criticism of Markus Hinterhäuser in saying that the piano version can’t really match the wonderful orchestral textures in the violin solo passage (from 1:58) despite the sensitivity of his playing; also, the bass line is more ‘present’ in the piano version and I prefer the softer yet firm foundation provided by double basses. That said, Grigorian’s voice soars again in the final stanza and I appreciate the way in which her pianist is demonstrably ‘with’ her. In the postlude I miss above all Strauss’s wonderful enrichment of the orchestral textures through his use of soft but telling horn parts.

There seem to be two schools of thought among conductors when it comes to the opening of ‘Im Abendrot’. Some adopt a sumptuous, broad speed – though no one is as broad, in my experience, as Kurt Masur for Jessye Norman in a version of the songs that I used to admire greatly but now think is somewhat overcooked, not least in the matter of slow speeds (review). The other school of thought is that the sumptuousness needs to be leavened with a greater degree of forward momentum. Mikko Franck subscribes to the latter school of thought, and I’m glad he does. As well as a memorable and moving vocal line, this song abounds in exquisite orchestral details: I think, for example, of the flutes illustrating the reference to a pair of larks, and of the subdued but glowing horn writing at ‘So tief im Abendrot’. All this and more is brought out in a very natural way by Mikko Franck and his orchestra and they provide distinguished support for Asmik Grigorian’s focused and very lovely singing. The long orchestral postlude is very well dome; the OPRF lays down a dark, rich carpet of sound over which, at the very end, the larks trill softly and sweetly.

The piano version is most interesting. Even more that in ‘September’ Grigorian and Hinterhäuser adopt a much more expansive approach: their performance lasts for 8:44 whereas the orchestral version plays for 7:16. The opening is broad and imposing– one can’t help but notice that the accompaniment is provided by an instrument that is percussive in nature. Interestingly, Grigorian manages to be even more expansive in her singing than she was with Mikko Franck, yet at the same time there’s intimacy and almost an element of confiding in the way she delivers the song. She puts the text over with great understanding: I love, for example, the way she judges the extent to which she should linger at ‘O weiter, stiller Friede!’ As for the accompaniment, Hinterhäuser plays with great sensitivity; it’s not his fault that on a piano the trilling larks are too ‘present’ as compared with the orchestral version. He invests the postlude with grave beauty; his playing is very inward and though the pace is daringly slow he pulls it off, even if I did find myself yearning for Strauss’s wonderful orchestral colours.

I found listening to this album was a fascinating experience. You’ll have gathered that I strongly prefer the songs in their orchestral guise. That said, the piano version presents fresh insights and I have to challenge myself by asking how much my preference for the orchestral version is swayed by my listening experience over more than five decades. You’ll find that this disc offers an excellent orchestral performance, sensitive pianism and distinguished singing. But I find myself coming back to an admiration for the way in which Asmik Grigorian has rethought her approach to the songs. Anyone expecting to hear the same vocal performance but with different accompaniments will be surprised. This, to me, is the hallmark of a very serious, thoughtful artist. Part of me would like to hear her sing the songs with orchestral accompaniment in the way that she approaches the piano version and at those tempi.

The recordings are very good. Inevitably, in the orchestral version the engineers present the performance in a bigger acoustic and with more of a sense of space. In the piano version the sound is closer but conveys more of what you’d expect to hear at a Lieder recital; in other words, a more intimate experience.

Normally, I’d say that one can’t overlook the short playing time of 44:15, but on this occasion I’ve come to the conclusion that one should overlook it. My first reaction when the disc arrived was that the playing time is mean. However, this is very much a project album and the addition of more music would be intrusive. I think we should look past the playing time and appreciate that this is a thoughtful project and, as such, a significant addition to the discography of the Vier letzte Lieder.

Help us financially by purchasing from