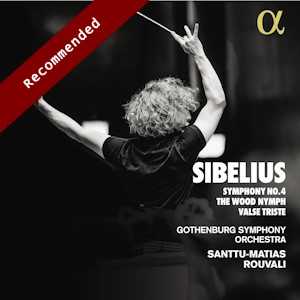

Jean Sibelius (1865-1957)

Symphony No. 4 in A minor, Op.63 (1909-11)

The Wood Nymph, Op. 15 (1894-95)

Valse Triste, Op. Op. 44 (1903-04)

Gothenburg Symphony Orchestra/Santtu-Matias Rouvali

rec. 2021-23, Gothenburg Concert Hall, Sweden

Alpha Classics 1008 [64]

Devoted as I am to Sibelius, I confess that his dark, grim Fourth Symphony has always hitherto baffled me – although I am equally aware that some Sibelians prize it above all the other six symphonies. However, when I saw that Santtu-Matias Rouvali had reached thus far in his ongoing cycle with the Gothenburg Symphony Orchestra, I could not resist reviewing it, especially as his previous releases of the first, second (review), third and fifth symphonies (review) have so impressed me.

I am well aware that this symphony was written during a low-point in Sibelius’ life and the brooding beauty of the opening cello solo underlines that, while also depicting how misery can be perversely stirring and even uplifting when tempered by heroic resistance. The opening four minutes before the brass call to arms and the subsequent meditation are as dense and challenging as anything Sibelius wrote and could not be played with greater intensity than that which the Gothenburg Symphony Orchestra summons up here – this is lovely playing, enhanced by the crystalline digital sound. Rouvali’s grasp of the arcing progress of the gradual accelerando and crescendo is masterly, so the sunburst at 8:45 comes as a blessed release and relief. Under Rouvali’s spell, for the first time, I perceive the opening movement as a coherent entity.

After such a revelation, my appreciation of the second movement – a scherzo, is it? Hardly – is tempered by my understanding that everything about this symphony – keys, harmonies, mood – is ambiguous and unsettling -and it is over before the listener has time to process it. The Largo slow movement is sumptuously played, lending it a Brucknerian weightiness – wonderful work from the bassoons and double basses – and as with the first movement, Rouvali’s grasp of its architecture enables the listener to be gently shepherded towards an embrace of its quiet resignation. The tinkling glockenspiel, pizzicato mutterings and bustling forward motion of the first half of the finale temporarily provide a meretricious sense of re-encountering a more familiar and reassuring Sibelian soundscape before a grinding clash of tonalities reasserts a mood of uncertainty. Again, the assurance and homogeneity of the orchestra’s playing here are key to conferring coherence upon the movement, and the bleakness of the eight, repeated A-minor chords ending it is startling.

The two fillers provide a welcome contrast. The main motif of The Wood Nymph is of course reminiscent of the Karelia suite and it has the kind of moto perpetuo energy which makes upbeat Sibelius so compelling. The Gothenburg orchestra makes a really deep, multi-layered sound here and Rouvali ensures that the tension never slackens over the full twenty-two-minute span – this is thrilling playing and conducting. The pause and reprise at 8:23 is breathtaking and the nobility of the bank of horns taking up the chorale is worthy of comparison with any of the world’s great orchestras. A second pause at 10:57 is neatly gauged before a shimmering string and pizzicato passage underpinning the solo cello’s depiction of the wood nymph’s seduction of Björn and the surrender of his soul to death in erotic union. As with the Fourth Symphony, it has taken this performance to lead me to a proper recognition of the allure of this music. The coda is wonderfully driven and climactic; the sonority of the orchestral sound is spectacular.

The familiar Valse Triste makes a wholly appropriate pendant to this death-laden programme. I have always favoured Karajan’s steady take on this music; Rouvali is rather more adventurous and fluid with it – indeed, daringly agogic – but he makes his rhythmic eccentricities interesting. Instead of a slow, inexorable winding down to oblivion he makes the piece a dramatic, episodic narrative. I’m not sure this is how I always want to hear this mini-masterwork but it is certainly stimulating – and different.

Ralph Moore

Help us financially by purchasing from