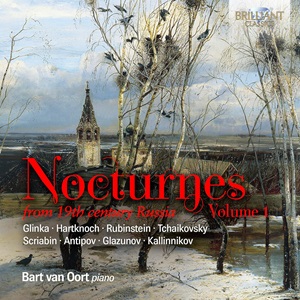

Nocturnes from 19th Century Russia – Volume 1

Bart van Oort (piano)

rec. 2022, Concert Hall Chris Maene, Ruiselede, Belgium

Brilliant Classics 96966 [65]

As well as being Volume 1 of Nocturnes from 19th Century Russia this is volume 6 of Brilliant Classic’s extended series The Nocturne in the 19th Century that began some 29 years ago with the nocturnes of John Field. The first four volumes are now available as a boxed set (Brilliant Classics 92202 review) though I can’t currently find availability of Volume 5, the 2014 release of French nocturnes. The present disc and its forthcoming companion follow in John Field’s footsteps and travel to Russia. Field had arrived in 1803 and quickly established himself as a concert artist, teacher and composer and his nocturnes and the influence of Italian bel canto can immediately be heard in the nocturnes of Glinka and Hartknoch. Both of Glinka’s reflect this though they come from very different parts of his career. The more mature Nocturne in F minor la séparation follows a simple ABA structure like the earlier E-flat nocturne though its melancholy and pathos is anything but simple. The earlier nocturne has much more contrast between the sections and echoes the music of Hummel and Glinka’s teacher Charles Mayer. Bart van Oort takes the opportunity to bring additional decoration to the reprise of the opening section of each nocturne, much as a singer would be expected to do and he brings quite delicate virtuosity to the task; the results are perhaps more in keeping with 19th century than modern practice, but I find it enchanting. Karl Eduard Hartknoch was a Riga born pianist who had several piano solos and two piano concertos to his name. Like Field, he moved to Russia, spending time in St. Petersburg and Moscow, where he wrote the three nocturnes op.8 a year before his early death. His nocturne in B minor sounds like early Chopin and is quite charming. Anton Rubinstein was a phenomenal pianist and quite prolific composer; there are 119 opuses, many of which are collections of pieces as well as several unpublished pieces; little is now is heard beyond an occasional outing for the D minor piano concerto and the once famous melody in F. The bel canto influence is now pretty much an integral element in the lyrical writing of romantic composers and with the far-reaching influence of Chopin and Liszt there is a greater variety of figuration and accompanying features as well as greater dramatic contrast noticeably within the nocturne genre. These three examples by Rubinstein show that he has a tuneful gift that extends beyond the sentimentality of his famous melody. The two later nocturnes date from the same period as the fourth piano concerto and Op 71 especially has echoes of the Liszt of the liebesträume or the Petrarch Sonnets.

Central to the recital as he was to 19th century Russian music is Piotr Ilych Tchaikovsky. His nocturnes date from the early 1870s, around the time of the second symphony and already have his melodic and harmonic trademarks; the chromatic rising sequences in bars 5 and 6 of Op 10 and the dramatic tension of the false relations in the repeated chord section of the same work. The Nocturne Op 19 is more familiar, a favourite of Shura Cherkassky’s, and its melancholy is only enhanced when he moves the tune to the cello register for the reprise accompanied by a capricious countermelody. The dance like central section makes a second appearance, combining with the triplets of the outer section in a tender coda. Alexander Scriabin’s early debt to Chopin is clear to see in the A-flat nocturne dating from his early teens; the simple melody sings over an arpeggio left hand and is pleasant if unremarkable. The repeated chords of the dramatic central section suggest familiarity with Tchaikovsky’s Op 10 though without the originality of harmony and it all seems a bit overly dramatic compared to the simple outer melody. The two nocturnes Op 5 written just four years later display much more of Scriabin’s own style, with hints of the enigmatic harmony and complex interweaving of parts; the opening of the second particularly is quite redolent of the writing in the first three sonatas. In the nocturne from the two pieces for left hand alone Op 9 a more mature Scriabin shows his teen self how to write a memorable melody and arpeggio accompaniment even with all the constraints of a single hand. It is a masterpiece of writing and a perfect example of just how capable the left hand can be, as well as being utterly beautiful to boot. Alexander Glazunov survived Scriabin by over twenty years, though his conservative writing never approached the harmonic audacity that Scriabin achieved before his relatively early age. That said, he knew his way around the keyboard and his D-flat nocturne is typical of his thick textured approach. A stately opening section belies the grandeur and passion to come, as well as the unease that grows out of an almost hymn like section theme. The return of the opening melody is full of richer textures and inner voices with an extended arpeggio accompaniment of the type that fills the score of his fellow Russians Balakirev and Lyapunov, both of whom are presumably candidates for Volume 2.

Konstantin Antipov is rather unknown now; he was Anatoly Liadov’s cousin and like Liadov he studied composition with Rimsky-Korsakov, though he seems to have attended more classes than his indolent cousin. His output was small, just thirteen opus numbers which are mostly short piano pieces, though there are a handful of songs and an Allegro symphonique for orchestra. The two nocturnes are both attractive works, with a healthy dose of melancholy in the first and the feel of a barcarolle in the second. He fits in here alongside Tchaikovsky and Rubinstein, whose Russian roots were combined with a more cosmopolitan outlook than composers such as Balakirev, Mussorgsky and their circle. Van Oort ends his recital with Vasily Kalinnikov’s tender Nocturne in F-sharp minor, one of just a handful of piano works he wrote in his short life; it lies between the melodic melancholy of Tchaikovsky and the skittish impetuousness of Scriabin and is a rather beautiful piece to end the first chapter of this Russian exploration.

Bart van Oort plays an 1875 Steinway and for me, it suits the music very well. The booklet points out that due to the age and condition of the period instrument some mechanical noises in the recording have been unavoidable, but I can’t say I noticed this distracting from the performances which are excellent. I am looking forward to hearing what rarities he uncovers in Volume 2.

Rob Challinor

Help us financially by purchasing from

Contents:

Michael Glinka (1804-1857)

Nocturne in F minor La Séperation (1839)

Nocturne in E-flat major (1828)

Karl Eduard Hartknoch (1796-1834)

Nocturne in B minor, Op 8 No 3 (c.1833)

Anton Rubinstein (1829-1894)

Nocturne in G-flat, Op 28 No 1 from Deux Morceaux (1856)

Nocturne in G, Op 69 No 2 from Cinq Morceaux (1867)

Nocturne in A-flat, Op 71 No 1 from Trois Morceaux (1867)

Piotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky (1840-1893)

Nocturne in F, Op 10 No 1 from Deux Morceaux (1871-72)

Nocturne in C-sharp minor, Op 19 No 6 from Six Morceaux (1873)

Alexander Scriabin (1832-1915)

Nocturne in A-flat WoO.3 (1886)

Two Nocturnes, Op 5 (1890)

Nocturne in D-flat, Op 9 No 2 for left hand (1894)

Konstantin Antipov (1859-1927)

Nocturne in F-sharp minor, Op 6 No 2 from Quatre Morceaux (1890)

Nocturne in A-flat, Op 12 (1892)

Alexander Glazunov (1865-1936)

Nocturne in D-flat, Op 37 (1889)

Vasily Kalinnikov (1866-1901)

Nocturne in F-sharp minor, No 3 from Quatre Compositions (1896)