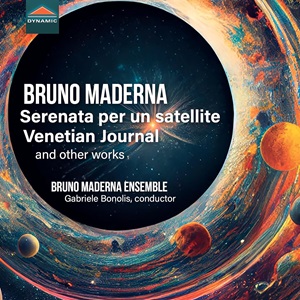

Bruno Maderna (1920-1973)

Serenata No 2 for 11 instruments (1957)

Honeyrêves, for flute and piano (1961)

Aulodia per Lothar, for oboe d’amore (1965)

Serenata per un satellite, for variable ensemble (1969)

Widmung, for solo violin (1967)

Venetian Journal, for tenor, orchestra and tape after James Boswell (1972)

Bruno Maderna Ensemble/Gabriele Bonolis

rec. 2023, Conservatorio Giovanni Battista Pergolesi, Fermo, Italy

Texts for Venetian Journal are not included in the booklet.

Dynamic CDS8008 (70)

If I were to be granted the opportunity to spend an evening dining, drinking and conversing with just one of the three great Italian provocateur composers born during the 1920s, I would certainly have chosen Bruno Maderna as my companion over Luciano Berio or Luigi Nono. He was well-known as a bon viveur – in the filmed clips or old pictures I’ve seen of him when he wasn’t working, he’s rarely without a glint in his eye or a cigar; listening to him leading rehearsals as a conductor or simply being interviewed towards the end of his life the intermittent cough which betrayed the lung cancer that killed him at 53 is certainly tough to hear, but not his apparent joie de vivre. The phrase ‘larger than life’ has followed him around during the half-century since his death.

By all accounts, Maderna was a mesmerising conductor. Fastidious in his preparation of new music (as is evident in the first of the links provided above) he was also a remarkable Mahler interpreter – his towering 1971 BBC performance of the 9th Symphony (released back in 2006 on the BBC Legends label – review) in my view is tragic, terrifying and utterly unforgettable – the slightly ropey sound barely dampens its impact. Yet the passage of time has reinforced the notion that he was primarily a formidable and productive composer. So why is it that I really, really struggle to ‘get’ much of his own output? Whilst his reputation seems to be dependent on the works of his maturity, the big orchestral pieces Quadrivium, Aura and Biogramma, the three Oboe Concertos (Maderna patently loved the instrument) and the opera Satyricon are generally held to be his most important creations – yet despite repeated attempts, I continue to seek a unique Maderna ‘style’ in vain. It’s an issue which simply doesn’t occur with either Berio or Nono. Perhaps unfashionably, I have actually found some of Maderna’s earlier pieces to be both more appealing and rewarding. In this regard, two discs stand out: a Naxos CD of exhilarating, early piano concertos (paired with Quadrivium – review) and an accessible, powerful Requiem dating from Maderna’s wartime partisan days which was long considered lost and was finally recorded in 2013 by Capriccio – review. Whilst the influences upon these pieces might seem pretty obvious, they are also fully absorbed within an approachable modern idiom which is both fresh and compelling.

On the other hand, I find Maderna’s many acknowledged later masterpieces to be relatively formless, embodiments perhaps of the rather lazy descriptor ‘all-purpose modernism’. Fortunately, I would not direct this criticism at all the works on this enterprising recent release from the Italian Dynamic label. The six pieces on the programme broadly encompass the whole of the second half of Maderna’s career as a composer.

Serenata No 2 from 1957 is scored for an ensemble of eleven players. It’s bookended by brief lyrical episodes which employ leisurely tempi. In between, the idiom takes on something of a pointillistic turn, with prominent contributions from harp, piano and tuned percussion. A central episode emphasises timbre and mood, featuring imaginatively deployed trills and tremolandi. Ultimately, the Serenata seems to be an attempt to incorporate Webernistic stylings within a more extended, occasionally songful form. Whilst this lively account by the Bruno Maderna Ensemble conveys detail and clarity, a rather dry acoustic slightly hampers the impact of what proves to be an attractive, neatly crafted piece.

The flautist Luisa Curinga is kept busy throughout the Serenata but steps more explicitly into the spotlight for the flute with piano miniature Honeyrêves. This compact piece dates from 1961, its title a delightful conflation of a made-up compound word which could mean ‘sweet dreams’ and a backwards ‘version’ of the name ‘Severino’ which many readers will realise alludes to the late, legendary Italian flautist Severino Gazzelloni. Honeyrêves itself projects a vital synthesis of melody and texture with piano accompaniment (provided here by Alessandra Gentile) which is intermittent, experimental and often percussive. Strings are occasionally plucked directly. For long periods, if the flute is the harbinger of melody, the piano is more of a disruptor.

Honeyrêves is followed by another brief solo piece, Aulodia per Lothar, for oboe d’amore. There is something archaic in this sequence of long-breathed and piquant melodic threads which truly suits this title. The eponymous dedicatee was Lothar Faber, who premiered many of Maderna’s oboe-inspired pieces. Aulodia is melodic and freewheeling, and Lorenzo Luciani’s account eschews the ad libitum guitar part which Maderna originally intended.

Widmung (Dedication) is a more extended work for single instrument, this time a solo violin. Commissioned in 1967 by Ottmar and Greta Dommick for the opening of their private museum of abstract art in Nürtingen, southern Germany, it takes the form of a soliloquy, In the booklet Nicola Verzina mentions the solo violin’s capacity for “…..gestural expressiveness that [can] recall real human relationships”. Adopting a similar language to the other solo and chamber pieces on this disc, in Widmung the composer seeks to blend the thorny and the lyrical; the piece was subsequently incorporated (as the cadenza) into Maderna’s Violin Concerto. It is performed here with apt severity and restraint by Aldo Campagnari. In this case, the acoustic seems slightly more benign.

Maderna’s Serenata per un satellite from 1969 is an aleatoric improvisation for flexible ensemble, in this case four players, flute, oboe d’amore, violin and piano. Interestingly it was commissioned for the launch of Boreas, an early European satellite which was launched (aptly) from Darmstadt whilst this piece was being premiered. Nicola Verzina informs us that this Serenata “…is written on a single large page where the staves criss-cross in a bizarre way (but with meticulous performance indications!)” – it is perhaps the latter which prevents the piece disintegrating into a complete free-for-all – indeed, several instrumental phrases recur and consequently suggest that the Serenata might be more tightly controlled than it actually is. To my mind, I’m afraid it still projects the rather anonymous type of generalised modernity to which I referred earlier.

The disc closes with an extensive and entertaining collage Venetian Journal, which makes use of a tape part as well as an instrumental group of 17 players. Premiered in 1972, it begins in medias res with taped extracts of Italian opera arias and folk songs fading in and out of blocks of primitive sounding percussion and concrete sounds, as if to plant the idea of a Venetian travelogue in the listener’s mind. This certainly creates a most atmospheric effect. Melodic fragments are slowed down and sped up, distorted and blown away. A pronounced American voice quotes Boswell. The tenor alternates speech and sung aspects of the text over a colourful instrumental tapestry which incorporates what I can only assume are fragments of Venetian vernacular music. Venetian Journal is certainly the most interesting offering on the disc and mystifying though its juxtapositions may be to listeners such as this reviewer who have never experienced the delights (or the dirt) of Venice for themselves. It certainly compensates for the academic dryness of some of the other works here. The work is enthusiastically performed by the Bruno Maderna Ensemble (under the baton of Gabriele Bonolis) and seems to have been more sympathetically recorded than the couplings. The tenor Gianluca Bocchino certainly makes the most of the exaggerated, ironic, multilingual references to hedonistic excess, enthusiasm for the arts and moralistic guilt which feature in Boswell’s text. There are plenty of colourful outbursts for the instrumentalists too, notably trumpet, bass clarinet and double bass. There is certainly a kinship with some of Berio’s more overtly theatrical pieces.

Good as it is to have the comparative rarity of a new Maderna collection, to my ears, alas, it seems that much of his music has dated more rapidly than that of several of his contemporaries, and not just those Italian compatriots to whom I referred earlier. Notwithstanding the excellence of the playing and Maderna’s undoubted historical significance, I suspect this disc is ultimately one that the specialist is more likely to appreciate than the general listener.

Richard Hanlon

Help us financially by purchasing from