Hues and Shades

Dathanna

rec. 2019-23, Dublin, Ireland

Orchid Classics ORC100278 [66]

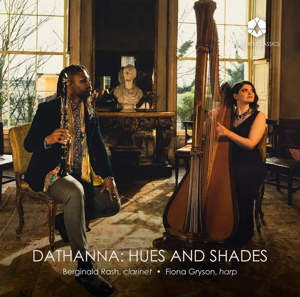

Dathanna, an excellent duo made up of clarinettist Berginald Rash and harpist Fiona Gryson, is new to me, and I was delighted to make their acquaintance. The booklet notes tell us that the ensemble was founded in 2016 and is based in Ireland. This last fact might have been deduced from their chosen name, since ‘Dathanna’ is an Irish word which means ‘colours’. This appears to be the duo’s first recording and what a fine debut it is: a delightful disc, mixing famous composers with the relatively obscure, everything played with sensitive understanding and thoroughgoing technical skill, the whole full of subtle and evocative music-making.

Fiona Gryson is Irish, while Berginald Rash is American-Irish, but now resident in Dublin. Both performers are clearly fascinated by what the booklet notes call “timbral hues and shades, colours of sound, phrasing, texture and virtuosity through musical expression” (the notes are said to be the work of “Berginald Rash, edited by Fiona Gryson and Fionnula Gryson”).

The earliest work is that by Bochsa, who died in 1856; the latest is that by Alamiro Giampieri, which was published in 1948 (though consciously written in the style of the Nineteenth Century. The disc’s centre of gravity, chronologically speaking, is the second half of the Nineteenth Century and the early decades of the Twentieth. As Rash writes, the album seeks to present “a soundscape reminiscent of the warmth and setting of 19th century salon music concerts” and, Dathanna succeed convincingly in doing this. No doubt, recording engineer Aidan McGovern deserves credit here too, as does the venue for the recording sessions, the Academy of Sound based in a townhouse on New Bride Street in central Dublin.

Of the nine composers represented on the disc eight are French, the one exception being the Italian Alamiro Giampieri. Very little of the music was originally written for clarinet and piano. Ravel’s Pavane pour une infante défunte, Debussy’s Petite Pièce and La Fille au Cheveux de Lin, along with Satie’s Trois Gymnopédies were all written for piano solo, while Ravel’s Pièce en forme de Habanera was written for bass voice and piano. Saint-Saën’s ‘Clarinet Sonata’ was composed for clarinet and piano, as were Pierné’s Canzonetta, Cahuzac’s Cantilène and Giampieri’s Il Carnevale di Venezia. Bozza’s ‘Aria’ was originally scored for alto saxophone and piano, while the score of Bochsa’s ‘Thème et Variations’, part of his Grande Sonata, specified that the work was for clarinet (or violin) and piano (or harp).

I assume, given the absence of any information contradicting this assumption, that all the pieces were adapted for clarinet and harp by the performers. All of the arrangements work well and without exception every track on the disc provides some delightful instrumental textures and a deal of beautiful music. Naturally, a few pieces stand out and deserve special mention.

One such is the gorgeous version of the Pavane pour une infante défunte. Ravel is reported to have said, surely not entirely seriously, that he chose the title because he liked the sound of the words! But in choosing them he surely didn’t ignore what they meant. For me, the key word (along with ‘Pavane’) is ‘infante’. English translations of the title usually give this word as ‘princess’ but it actually has a more precise meaning. It is a French translation of the Spanish word ‘infanta’, i.e. “a daughter of the ruling monarch of Spain, specifically the eldest daughter who is not heir to the throne” (Oxford English Dictionary). As Norman Demuth puts it (Ravel, 1947, p.10), “the whole raison d’être of the work is the stately pavan danced in front of the bier of a Spanish princess, which dance was a characteristic one of old Spain”. I have read several writers who report that Ravel said that he had in mind an Infanta of the kind depicted by Velasquez, but I cannot vouch for the authenticity of this supposed remark. It is undeniable, however, that Spain and its music(s) were always important to Ravel; his “mother was Basque and sang Spanish folk-songs to him from his infancy” (James Gibb, Keyboard Music, ed. Denis Matthews, Penguin Books, 1972, p.274). The Pavane pour une infante défunte belongs with other works by Ravel such as ‘Alborada del gracioso’, from (Miroirs, 1904-5), the Pièce en forme de Habanera (1907), Rhapsodie espagnole (1909), Bolero (1928), and Don Quichotte à Dulcinée (1932-33), all of which have, to borrow a phrase coined by Jelly Roll Morton, a “Spanish tinge”. In the case of Pavane pour une infante défunte that Spanish quality emerges more fully in this version for clarinet and harp than it does in either the original piano version or Ravel’s orchestration thereof. Guitar-like chords and figurations emerge with particular clarity in the plucked sound of the harp. Ravel dedicated the Pavane pour une infante défunte to the Princesse de Polignac (née Winnaretta Singer), who regularly hosted private concerts at her mansion in Paris’s Avenue Henri Martin. It seems quite likely that Ravel played it there in more than one such concert. That background makes it a particularly suitable choice for this recording, given the Dathanna’s desire to create a “soundscape reminiscent of the warmth and setting of […] salon music”. Indeed, though it may smack of heresy to say so, I find myself enjoying this particular arrangement of Pavane pour une infante défunte morethan either the original version for solo piano(for its greater range of colours) or Ravel’s version for orchestra (for its delightful intimacy).

Another highlight is Saint-Saëns’ Clarinet Sonata. Though I cannot say, this time, that I prefer this new version to the original score for clarinet and piano, it is certainly good to have and hear this alternative version, which freshens up one’s responses to the music in the process of defamiliarizing the familiar. The opening passage of the first movement, in which an attractive berceuse-like melody is heard above a series of calm eight-notes, is one instance where the harp is perhaps preferable to the piano. The moment when that quasi-lullaby returns after some stormier music is one of the highlights of this lovely, and loving, performance. Though written in the last year of the composer’s life only the third movement (Lento) sounds somewhat autumnal, even elegiac. The second movement (Allegro animato) introduces that Lento by way of contrast, being, in the words of Berginald Rash, “fun, spritely and bouncing filled with whirls and spins in the clarinet and harp”. These two instruments seem particularly appropriate here. More so, indeed, than in that much graver third movement – the one place where I seriously doubted this adaptation. The last movement (Molto allegro) is, again, full of energy and, in echoing material from the first movement completes a fascinating musical circle.

The first of Satie’s Trois Gymnopédies fares particularly well in this translation for clarinet and harp. Satie’s piano pieces lend themselves well to sympathetic arrangement, and this is one of the loveliest I have heard, not least because it respects the apparent simplicity of the original. Rash and Grysin do full justice to the piece, Rash’s long lines being a thing of rare and special beauty.

Of the lesser-known works, I found particular delight in Louis Cahuzac’s ‘Cantilène’. For much of the Twentieth Century Cahuzac was a significant figure as a clarinettist and a teacher of his instrument (Gervase de Peyer was among those who studied with him). He was born at Quarante in Languedoc and studied at the Conservatoire in Toulouse, before going on to further study at the Paris Conservatoire where, in 1899, he was awarded first prize in clarinet. He went on to a distinguished career as a soloist whose interpretative skills were valued by significant composers. So, for example, he performed Debussy’s Première rhapsodie, with the composer at the piano, while Milhaud dedicated his ‘Sonatina for clarinet and piano’ to Cahuzac, and in 1956 (at the age of 76) he recorded Hindemith’s Clarinet Concerto, conducted by the composer. Cahuzac’s own compositions were, I believe, all for the clarinet, including ‘Fantaisie sur unvieil air champêtre’, ‘Pastorale cévenole’and ‘Variations sur un air Pays d’Oc’; I have very distant memories of hearing the last of these played by a student pianist and a student clarinettist in Oxford’s Holywell Music Room around 1970. As some of those titles suggest, Cahuzac’s music often rememberedwith pleasure, and evoked, the area of France in which he grew up. That is also true of his ‘Cantilène’, beautifully played on this recording – a lyrical remembrance at times nostalgic, yet quietly but affirmatively celebratory. Berginald Rash’s notes fittingly describe it as “a single-movement work in A-flat Major that employs a jubilant cantabile tune in the clarinet supported judiciously and lovingly in the harp that returns again and again, each time more insistently and more lovingly” – a description which does justice both to Cahuzac’s craftsmanship and the rich emotion of the piece. This performance makes me want to hear more of Cahuzac’s compositions.

Richly enjoyable, this disc is full of subtle and evocative music-making and full, too, of pleasant surprises. I am, as I hope I have made clear, full of admiration for the skills of the two performers and for the evident empathy between them.

Glyn Pursglove

Help us financially by purchasing from

Contents

Gabriel Piernè (1843-1937)

Canzonetta, Op. 19 (1888)

Louis Cahuzak (1880-1940)

Cantilène (publ. 1971)

Camille Saint-Saens (1835-1921)

Clarinet Sonata, Op. 167 (1921)

Maurice Ravel (1875-1937)

Pavane pour une infante défunte (1899)

Pièce en forme de Habanera (1907)

Eugène Bozza (1905-1991)

Aria (1936)

Erik Satie (1866-1925)

Trois Gymnopédies (1888)

Nicholas Charles Bochsa (1789-1856)

Thème et Variation

Claude Debussy (1862-1918)

Petit Pièce (1910)

La Fille au Cheveux de Lin (1909/10)

Alamiro Giampieri (1893-1963)

Il Carnevale di Venezia, Capriccio variator (publ 1948)