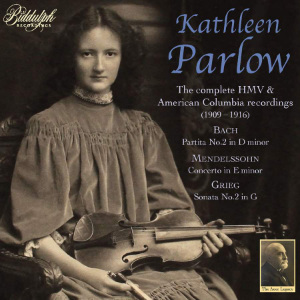

Kathleen Parlow (violin)

The Complete HMV and American Columbia Recordings

rec. 1909, London: 1912-1916, New York; 1941 and 1957, Canada

Biddulph 85036-2 [2 CDs: 158]

Canadian violinist Kathleen Parlow (1890-1963) shared the distinction of being, with her contemporaries Efrem Zimbalist and Mischa Elman, a leading exponent of Leopold Auer’s training. She gave the Belgian premiere of the Glazunov Concerto, on the composer’s recommendation, in 1907, was signed by HMV two years later – she was still in her teens – and based herself in England until 1925. Her early tours with the Beecham Symphony impressed the leader of the orchestra, Albert Sammons, who remembered her as the most impressive female violinist he had heard – perhaps his admiration was increased by the number of different concertos she performed on the orchestra’s famously barnstorming British tour during October 1909: Saint-Saëns No.3, Bruch, Glazunov, Halvorsen, Tchaikovsky and Brahms.

Parlow hasn’t fared well when it comes to reissues. Pearl included a couple of her sides in a volume of the Violin on Record and APR included all four of her HMVs in their Auer Legacy but otherwise the large part of her legacy has been ignored. I’ve never come across a single CD devoted exclusively to her recordings which makes this twofer even more welcome.

Those early HMVs show her splendid facility in Paganini’s Moto perpetuo – fast and precise – as well as her stylistic affinity in the two Halvorsen pieces with the added advantage of her sheer charm. Her anonymous pianist was very well recorded and there is a successful balance between the two instruments. Fortunately, this collection has been compiled in strict chronological order rather than grouped by composer, so that it charts the course of her recorded career accurately. It should be noted that she never made any commercial electric discs and that these are all acoustics, from the four HMV sides through the 1912-16 American Columbias, many of which were also released in Britain on British Columbia. (I’ll have something to say about the CBC broadcasts which form a generous appendix.)

She essayed the usual sweetmeats expected of fiddlers of the time, genre pieces with anonymous accompaniments though when she was granted a piano accompanist it was Charles Adams Prince. She is a proficient Kreisler performer though occasionally cavalier rhythmically, something that applies to her Chopin arrangements. Thomas Moore’s The Last Rose of Summer is appropriately refined and even elfin – very different in other words to Elman’s combustible flower, one that burns in the dying light under his fleshy fingers. For all her chaste double-stopping I think you’d rather luxuriate in his voluptuary splendour. Unfortunately, as so often with violinists of the time, she was often accompanied by a brass bandy little ensemble, not by a piano – I disagree completely with note writer Wayne Kiley (otherwise fine) that this in any way attests to her status. If anything, it actually signifies the opposite. Kreisler, Heifetz and Elman all had piano accompaniments not ersatz salon-style ones, and so did Maud Powell and Ysaÿe.

Technically speaking she has a long bow, a fast trill and is rhythmically buoyant, not least in Bach’s Gavotte from the Partita No.3. But she can lack ardour sometimes, as she illustrates in the central section of Arensky’s Serenade and whilst she is sweetly reserved in Massenet, sweetly reserved isn’t always enough for expressive commitment. One can also hear in her teacher’s arrangement of Tchaikovsky’s Melodie in E flat that she prefers to float than emote and the result is a little small-scaled. In April 1916 Columbia asked her to record Sarasate’s Habanera from Carmen, which she did adeptly, and then to re-record five things she’d recorded only four years previously. Presumably they had faith in their increased recording fidelity over that brief period – I suspect you’ll find it hard to hear – though it’s a shame they didn’t increase the range of her discography instead.

That’s the extent of her HMV and Columbia discography – just 30 sides. However, she did also record for Edison, firstly in around 1912 – the same time she contracted to record for Columbia. These are not included. Nor are her Nipponophones, around 13 sides of which were recorded during her tours to Japan in 1922-23 with pianist Willy Bardas. Though both labels had a fixation with re-recording staples from her discography there are new things in the Edisons and Nipponophones so perhaps one day we will have them on CD as well.

There was plenty of time for her to have recorded again before she withdrew from the concert stage in the late 1920s, taught in New York in the 1930s, and returned to Canada where she devoted herself largely to teaching and to her string Quartet. However, after her last 1916 recording and those Japanese recordings nothing more was to be heard from her. She seems to have had financial problems, as well as an overbearing mother, and there are suggestions that she had a breakdown in the late 20s.

So, it’s a good thing that CBC made some recordings of her in the 1940s and 50s and these have been circulating among collectors for years. Even I have the Mendelssohn Concerto on CD. It’s from a CBC Symphony broadcast conducted by the British-born ex-fiddler Geoffrey Waddington (1904-1964). He had moved to Canada as a child and was to make a few recordings before his sadly premature death. He’s a bluff character on the rostrum but ears should instead be on Parlow as this is her only known surviving concerto recording. Her slides in the opening bars are rather gruesomely Old School and some of her playing is decidedly awkward, though she is more stylistically apposite in the slow movement and is more confident in an exciting finale. She had only just returned to Canada to teach at the University of Toronto so one wonders how much practice she had under her belt – as well as the last time she’d given a concerto performance. Later in the year there was the opening movement (only) of the Grieg Sonata No. 2 with Ernest MacMillan as pianist, a rather winning example of her circumscribed tonal qualities and stylish affinity with Nordic music.

She certainly played the Sibelius Concerto around this time and continued to broadcast quite widely – including the Bach solo Sonatas and Partitas and the Elgar Concerto, it would seem. Whether they have survived is doubtful but it would be good to think they have. But what has survived is a broadcast on 15 January 1957 when she was 66. There’s just the Andante from Bach’s Sonata in A minor. It may lack tonal breadth and she was at a dangerous age for a violinist but it’s a creditable performance. Of more significance is the whole of the Second Partita given on the same broadcast. Her lower strings aren’t as vibrant as her upper ones but that is something that was true of her recordings back in 1912. She glides through the Partita in some style and when it comes to the Chaconne she gives a wholehearted reading. True, there is roughness in some of her shifts but her dynamics are finely conceived and she gets around the notes. One can hear her audibly tire around nine minutes but she fights through and brings her direct, unshowy technique to bear. Unlike most other violinists she ends the Chaconne mired in deep melancholy.

I like the transfers. Maybe the fact that the collector Raymond Glaspole is listed as one of the transfer engineers – I assume many of the 78 copies used are from his collection – has something to do with that; the sound is forward and Parlow’s violin is well caught. Top has been retained and there’s no sign of roll-off or any horrible use of noise reduction.

This is a long overdue salute to Parlow, a patrician artist of technical legerdemain and discreet tonal qualities.

Jonathan Woolf

Help us financially by purchasing from

Contents

CD1

Niccolò Paganini (1782-1840)

Moto perpetuo, Op.11

Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750)

Air; Air on the G String arr Wilhelmj

Johan Halvorsen (1864-1935)

Mosaique No.4 ‘Chant de Veslemøy’

Danse norvégienne in A, No.2

Fryderyk Chopin (1810-1849)

Nocturne in D, Op.27 No.2 arr Wilhelmj

With anonymous pianist

rec. 1909

Franz Schubert (1797-1828)

Moment musicale No.3

Riccardo Drigo (1846-1930)

Valse bluette arr Auer

Fritz Kreisler (1875-1962)

Liebesfreud

Fryderyk Chopin

Nocturne in E flat, Op.9 No.2 arr Sarasate

Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827)

Minuet in G arr Burmester

Thomas Moore (1779-1852)

The Last Rose of Summer

Antonín Dvořák (1841-1904)

Humoresque in G

Anton Rubinstein (1829-1894)

Melody in F

Johann Sebastian Bach

Gavotte from Partita No.3 in E, BWV1006

Anton Arensky (1861-1906)

Serenade

Riccardo Drigo

Serenade, Op.30 No.2 arr Auer

Jules Massenet (1842-1912)

Méditation arr Marsick

Antonín Dvořák

Indian Lament from Violin Sonatina in G

Fritz Kreisler

Tambourin chinois, Op.3

Henryk Wieniawski (1835-1880)

Garden Scene from Gounod’s Faust

Pietro Mascagni (1863-1945)

Intermezzo from Cavalleria rusticana

Felix Mendelssohn (1809-1847)

Andante from Violin Concerto in E minor, Op.64

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky (1840-1893)

Melodie in E flat, Op.42 No.3 arr Auer

Johan Svendsen (1840-1911)

Romance in G, Op.26

With Charles Adams Prince (piano): orchestral accompaniment

rec. 1912-16

CD2

Pablo de Sarasate (1844-1908)

Habanera from Fantasie on Bizet’s Carmen

Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827)

Minuet in G arr Burmester

Franz Schubert (1797-1828)

Moment musicale No.3

Thomas Moore (1779-1852)

The Last Rose of Summer

Riccardo Drigo (1846-1930)

Valse bluette arr Auer

Fryderyk Chopin

Nocturne in E flat, Op.9 No.2 arr Sarasate

With Charles Adams Prince (piano): orchestral accompaniment

rec. 1916

Felix Mendelssohn

Violin Concerto in E minor, Op.64

CBC Symphony Orchestra/Geoffrey Waddington

rec. November 1941

Edvard Grieg (1843-1907)

Violin Sonata No.2 in G, Op.13: I Lento doloroso-Allegro vivace

Sir Ernest MacMillan (piano)

rec. November 1941

Johann Sebastian Bach

Violin Sonata No.2 in A minor, BWV1003; III Andante

Violin Partita No.2 in D minor, BWV1004

rec. January 1957