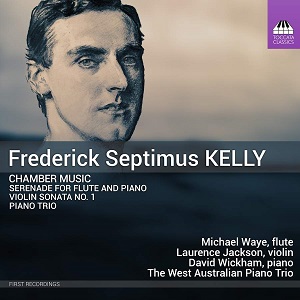

Frederick Septimus Kelly (1881-1916)

Violin Sonata No 1 in D minor (1901)

Serenade for Flute and Piano, Op 7 (1911)

Piano Trio (c.1905?)

Laurence Jackson (violin), Michael Waye (flute), David Wickham (piano)

The West Australia Piano Trio

rec. 2021/2022, Crank Recording, Perth, Australia

Toccata Classics TOCC0702 [66]

Pianist David Wickham’s insightful notes (from which I will quote with thanks) call Frederick Septimus Kelly ‘The Lost Olympian’. Born in Sydney in May 1881, he had a very significant career as a pianist and composer ahead, and he was an Olympic rower. His death at thirty-five whilst in action on the Somme was a loss especially to Australian music.

It is amazing how much music Kelly did compose. Recordings include a two-disc set ‘A Race against Time’ on ABC Classics (481 4576) of songs and piano music. Another double album on ABC Classics (review) contains orchestral works, including his best known Elegy in memoriam Rupert Brooke (who had died not long before Kelly), often heard on Remembrance Sunday. Toccata Classic has already released his piano music (review).

The orchestral twofer includes the Serenade for flute, harp, horn and strings. On this disc, we have Kelly’s version for flute and piano. He wrote it when he was sailing to Sydney from England, as a response to hearing flautist John Lemmone who played in an on-board ensemble. The booklet has the following to say about the Serenade’s five movements. The Prelude is ‘a pleasing confection of French flute music and the English folk idiom’. The longest movement, Idyll, is the ‘most exploratory and original of the set harmonically’. In the Minuet, Wickham hears ‘stout cornemuse-like pedals and horn calls that duet with the flute’. The Air and Variations reminds us further of the intended neoclassical elements in the work. The Jig finale is in ‘a Purcellian measure with a French structure and rhetoric’. The whole is perfectly balanced, civilised and charming.

Even if not the first, Kelly’s Violin Sonata No 1 may have been the most significant of the genre by an Australian at that time. Its twenty-six minutes tell us that it was meant as a major statement. Kelly was only twenty at the time. After his education at Eton, he attended Balliol College, Oxford. His father Thomas fell gravely ill, so Frederick had to sail back home. The work was composed there, and the initial performer was Kelly’s clearly talented brother Bertie.

The first of three movements begins with a portentous, even tragic, Adagio before embarking on a sonata-form Allegro vivace. The second subject is particularly memorable, as is the opening theme of the Andantino movement. For me, Kelly is at his best when he is thoughtful and does not overcrowd his ideas with too much counterpoint. The dramatic Allegro vivace finale, as David Wickham says, is a considerable nod towards Mendelssohn, and Brahms is never too far away. But it is what one would expect of a very young composer at that period. Still, he demonstrated an almost prodigy-like understanding of writing for the violin and indeed for the accompanying piano. One wonders how Kelly’s music might have developed had he lived longer.

It is thought that the Piano Trio is incomplete, as it consists of only two movements. The long first, marked Lento (moderato), is an intense and powerful utterance. It again looks to Brahms and Mendelssohn. The second movement is a rather Dvořákian brief, quick-silver Scherzo and Trio. Was the work ever completed at all, or will more movements turn up one day? Perhaps Kelly had to concentrate on the sport of rowing. The booklet says: ‘His solo sculling record of 1905, established at Henley-on-Thames, stood unbeaten until 1938. In 1908 he was a member of the British eight that won a gold medal in the London Olympic Games.’

No matter. The Piano Trio torso is a fine work. It presages a composer who could well have made a significant mark on early twentieth-century music. It is wonderfully performed, as are the other pieces on this disc. The musicians appear to be incredibly committed musicians and to really believe in this music. David Wickham should especially take a bow. He has prepared the editions and scores for this recording. But let us face it: the music points to potential. Except for a few sections in each work, it lacks a memorably strong individuality. Even so, one hopes for more music like this in future projects.

Gary Higginson

Previous review: Jonathan Woolf (October 2023)

Help us financially by purchasing from