Antonio Cesti (1623-1669)

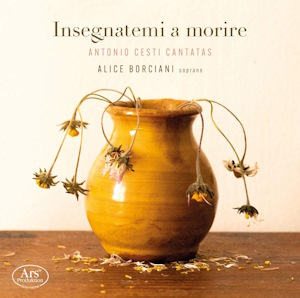

Insegnatemi a morire – Cantatas

Alice Borciani (soprano)

Ensemble Il Zabaione Musicale

rec. 2021/22, Tonstudio Waldenburg, Switzerland

Ars Produktion ARS38640 [56]

The Italian secular cantata is quite popular among performers of our time. That is easy to understand: the texts include often strong emotions, which allow performers to show their skills in the department of expression. They are also easy to perform in that the scoring is modest: mostly just one voice and basso continuo, sometimes with a few additional instruments. Most recordings concern cantatas by Alessandro Scarlatti and composers of later generations, such as Vivaldi or Porpora. In comparison, the cantatas written before Scarlatti are little-known, with the exception of those by Barbara Strozzi. A composer whose name is better known than his music is Pietro Antonio Cesti. Seven of his cantatas figure on a disc recorded by Alice Borciani and the Ensemble Il Zabaione Musicale.

Cesti was born in Arezzo, where he started his musical activities as a choirboy in the cathedral. He joined the Franciscan order at Volterra in 1637. In 1634 he became organist at the cathedral of Volterra and soon after also maestro di cappella. At some moment he came under the patronage of the Medici family in Florence. He had strong ties with several people and circles in that city. Despite his appointments as a church musician the core of his activities was in the field of opera. As a tenor he sang in several opera productions, among them in the Florentine premiere of Cavalli’s Giasone. Cesti’s first opera, Alessandro vincitor di se stesso, was performed in Venice in 1651. The next year he was appointed Kapellmeister at the court of Archduke Ferdinand Karl at Innsbruck, where he stayed for five years. There his opera L’Argia was performed in 1655 at the honour of Queen Christina of Sweden, who had abdicated after her conversion to Catholicism, during her visit at Innsbruck on her way to Rome. According to witness accounts that performance lasted more than six hours. Other operas followed, among them L’Orontea (1656). After staying in Rome and Florence from 1658 to 1662 he returned to Innsbruck, and in 1666 he became deputy Kapellmeister at the imperial court in Vienna. In 1667 he composed another long opera, Il pomo d’oro, at the occasion of the wedding of Leopold I and Infanta Marguerita of Spain. That or the following year he left Vienna and returned to Florence, where he died in 1669.

Early in his career René Jacobs gave Cesti quite some attention, recording his opera L’Orontea and some of his cantatas. In 1980 he put together a pasticcio of extracts from operas by Cesti, which he performed in Innsbruck, together with the soprano Judith Nelson. The recording of this live performance was released by ORF. These forays into his oeuvre seem not to have resulted in a substantial number of recordings. Several of his operas are available on disc, and his cantatas have been the subject of recordings, but otherwise most of his music is included in anthologies. As far as I have been able to find out, the cantatas performed here are new to the catalogue; only Insegnatemi a morire seems to have been recorded before.

The soprano Emöke Baráth included one of Cesti’s cantatas in a programme which is largely devoted to Barbara Strozzi (Erato, 2019), and that makes much sense, as her cantatas show strong similarity with those of Cesti. They are rather free in structure and have little in common with the cantatas by Scarlatti and later generations, which consist of clearly separated recitatives and arias. Here the transition from recitative to arioso and aria is fluid. It is the text and the affetti which are decisive for the form Cesti adopted. It is notable that whereas later composers used texts which were pretty much standard and not written specifically for a composition, Cesti worked closely together with the poet Giovanni Filippo Apolloni, who is the author of the lyrics of all the cantatas performed here. Alice Borciani, in her liner-notes, states: “The theme of love, often accompanied by hints of bitterness and sorrow, is treated by Apolloni with the awareness of a poet who can judge the demands a composer would have on poetry when setting it to music. The poetic material is deliberate and articulate in its choice of metric and is rich in rhetorical devices which Cesti skilfully sets to music using a wide and complex range of musical compositional techniques and gestures. The result is an anthology of refined compositions that are highly varied in terms of length, narrative structure and melodic creativity.”

The summaries of three cantatas may give an impression of what they are about. Alpi nevose e dure: “The classical theme of unrequited love is treated in the first person in this short cantata. The protagonist asks the Alps to hide the blinding, disturbing sun from him (a metaphor for the beloved) and to show him the way to death, which is the only way to free him from his torment.” Insegnatemi a morire: “The protagonist turns to the stars, the ‘Numi’, who guide his bitter destiny, and begs them to tell him how to end this torment in the most drastic way: through death.” That’s all pretty heavy stuff. Quanto sete per me pigri is different: “‘The Impatient Lover’, the title of Apolloni’s poem, aptly describes the content of this cantata. The protagonist, who always speaks in the first person, turns to Time and asks it to speed up the hours that separate him from the moment when he will meet his beloved.”

Ms Borciani mentions that Cesti makes use of various ways to illustrate the text, linking up with the tradition of madrigal composers of the late 16th century, such as word painting, harmony and rhythmic variation. It is regrettable that for those listeners who don’t understand Italian, it is impossible to observe the connection between text and music. The booklet includes the lyrics, but no translations. In recordings like this one, where the texts are not generally known and cannot be found at the internet (unlike liturgical texts), translations in a common language as English are in fact indispensable. The omission is all the more unfortunate, as Cesti’s music is seldom performed and recorded, and deserves to be better known. The short summaries in the booklet are helpful, but no compensation.

That said, even without understanding the text, this disc can be enjoyed. That is due to the quality of the music: Cesti undoubtedly was a great composer, and those who know some of his operas will recognize that. It is also due to the performance. Alice Borciani edited the cantatas, put together the programme and wrote the liner-notes. This is definitely a labour of love, and that shows. Her performances are excellent; even when one does not understand the texts, the various emotions in the cantatas are eloquently conveyed and communicated to the listener. She takes the right amount of rhythmic freedom in the recitativic episodes, and she makes effective use of the messa di voce, an important tool of singers in the 17th century.

I should not forget to mention the members of the ensemble Il Zabaione Musicale. Orí Harmelin (theorbo) and Elam Rotem (harpsichord) deliver excellent support in the basso continuo, and Eva Saladin and Sonoko Asabuki are responsible for the fine performances of the instrumental pieces by Giovanni Buonaventura Viviani, a contemporary of Cesti, who worked for some time in Innsbruck, where they must have met. These pieces are inserted as welcome breathing spaces between the often heavy emotions exposed in Cesti’s cantatas.

Johan van Veen

www.musica-dei-donum.org

twitter.com/johanvanveen

Help us financially by purchasing from

Contents

Antonio Cesti

Lasciatemi in pace

Giovanni Buonaventura Viviani (1638-1692)

Aria sesta

Antonio Cesti

Alpi nevose e dure

Insegnatemi a morire

Giovanni Buonaventura Viviani

Symphonia seconda

Antonio Cesti

Ricordati mio core

Quanto siete per me pigri, o momenti!

Giovanni Buonaventura Viviani

Aria terza

Antonio Cesti

Piangente un dì, Fileno

Ferma Lachesi, ohimé