Déjà Review: this review was first published in July 2004 and the recording is still available.

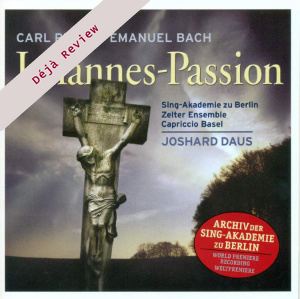

Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach (1714-1788)

Johannes-Passion (1772)

Elisabeth Scholl (soprano); Alexandra Petersamer (contralto); Gunnar Gudbjörnsson (tenor: Evangelist); Jochen Kupfer (bass: Jesus); Maximilian Schmidt (Pilatus); Julio Fernández (tenor, Petrus); Stefanie Dasch (soprano, Maid); Simon Berg, Daniel von Berndsdorf (Servants)

Zelter-Ensemble der Sing-Akademie zu Berlin

Barockorchester Capriccio Basel/Joshard Daus

rec. live, 9 September, 2003, Kammermusiksaal, Philharmonie, Berlin

Text and translation included

Capriccio C60103 [2 CDs: 87]

This is an important document, not least because what is actually captured on these discs is the first performance of this work since 1772. The score is presently housed in the archive of the Berlin Sing-Akademie after its discovery in the Ukraine. C.P.E.’s version of the Christ story is a dynamic one, with plenty of drama and much interaction between the various soloists and the chorus – a chorus that represents the Jews as well as performing the chorales.

C.P.E. has, perhaps rightly, accrued a reputation as being somewhat eccentric, an impression surely gleaned from some of his keyboard works in particular. In the present instance that aspect of his persona is not particularly pronounced although some distinctly jerky lines in the strings in the work’s first aria, track 9, for contralto, ‘Liebster Hand! Ich küsse dich’, remind us just who the composer is. What is in evidence, though, is a remarkably wide expressive vocabulary that he uses at all times appropriately to the situation.

The Johannes-Passion sees C.P.E. indulging in ‘parody’ (i.e. using other composers’ music for his own ends – there was no copyright then, remember). Certainly his model appears to be Telemann’s Johannes-Passion. C.P.E. also turned to a Passion by Gottfried Heinrich Stölzel for four of the arias and duets, plus the occasional nod towards his father, J.S. As the booklet notes put it, ‘So far as is known, the two arias ‘Verkennt ihn nicht’ and ‘So freiwillig, ohne Klage’ are the only parts actually composed by Carl Philipp Emanuel himself’!

What matters, of course, is the end result. The devotional chorale that sets the work on its path, ‘Erforsche mich, erfahr mein Herz’ (‘Examine me, prove my heart’) determines the tone. In performance terms, it is true we are not dealing with the Bach-Collegium Japan here, but this is still carefully shaped and balanced singing. These traits are to characterise the choral contributions throughout, right up to the final chorus (‘Ruht wohl, ihr heiligen Gebeine’; ‘Rest well, ye holy bones’) and the finale Chorale (‘Darum woll’n wir loben’; ‘So let us praise’). As protagonists (as the Jews, mentioned above), the choir seems to relish its involvement in the action.

The Evangelist on this occasion is Icelandic tenor Gunnar Gudbjörnsson (since 1999 on the payroll of the Deutsche Oper, Berlin, and Walther in Barenboim’s Teldec Tannhäuser). His voice is pleasing (and nicely suited to this repertoire, on this hearing), his diction excellent and he provides a real highlight of the set in his aria on the subject of Christ’s noble bearing of suffering (CD2, track 2). At a smidgen under ten minutes, this aria represents the longest single movement of the entire piece.

Jochen Kupfer is a fairly well-known name (listed here as a bass), having recorded with Sinopoli (Friedenstag) amongst others (even Suzuki on the BIS cycle of Bach Cantatas). He certainly carries authority as the Saviour, and his aria, ‘Verkennt ihn nicht, den Gott der Götter’ (‘Do not misjudge him, God of Gods’, CD 1 track 19) is a gem (and how the orchestra digs in here, full of life). The arias really do seem to be the highlights of this work.

Soprano Elisabeth Scholl has a pure voice and is eloquent except when her voice hits the higher reaches, where she can become shrill. This can be heard in her extremely sad aria, ‘Unbeflektes Gotteslamm!’ ‘(Unspotted Lamb of God!’, CD 1 track 23), an aria lifted to the heights by the miraculously intertwining violin parts. Alexandra Patersamer has a rich contralto voice that graces ‘Liebste Hand! Ich küsse dich’ (‘Dearest hand! I kiss thee’), leaving one wishing this aria is longer than its 5’41 duration.

The weakest of the soloists comes in the form of Maximilian Schmidt’s rather tremulous Pilatus.

Structurally, perhaps the music on the second disc is marred by too long a stretch of recitative, so that the chorus ‘Oh, ein grosser Todesfall!’ (‘O, a great occasion of death!’) comes as a welcome event. This chorus actually represents a touching meditation on Jesus’ death.

The whole seems admirable paced and balanced orchestrally by Joshard Daus (apparently a Celibidache disciple). The greatest compliment I can pay this performance is that the standard is so high it is difficult to believe it is taken down live. Only the undeniable concentration from first note to last attests to this.

If you are even vaguely curious, I do recommend you hear this work. It contains moments of great beauty as well as operating on a real dramatic trajectory which only serves to emphasise its moments of repose.

Colin Clarke

Help us financially by purchasing from