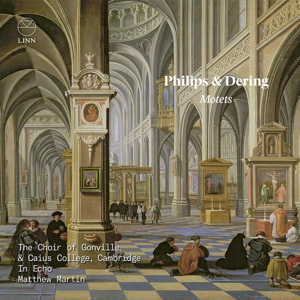

Peter Philips (1560/61-1628)

Richard Dering (c1580-1630)

Motets

In Echo

The Choir of Gonville & Caius College, Cambridge/Matthew Martin

rec. 2022, Holy Trinity Church, Minchinhampton, UK

Texts and translations included

Reviewed as a stereo 16/44 download from Outhere

Linn CKD717 [62]

It makes sense to bring Peter Philips and Richard Dering together in one recording. They were contemporaries, although Dering was twenty years Philips’s junior, and therefore was of a different generation. Both worked for some time at the continent, more in particular the Spanish Netherlands, which was firmly in the hands of Catholic rulers. That was just as well for both of them, as they were Catholics. Working conditions for people like them were not easy under the rule of the staunchly Protestant Elizabeth I. Their older peer William Byrd knew everything about that, but he had the good fortune that the Queen very much appreciated his music, which allowed him some freedom to be active as a composer.

The backgrounds of the two composers were different, though. Philips was born and bred Catholic, and emigrated for religious reasons. He never returned, and died in Brussels, where he had been active as an organist. Dering was born Protestant, and went to Italy in the retinue of Sir Dudley Carleton, the English ambassador to the Republic of Venice. It is assumed that in his time in Italy he converted to Catholicism. When Carleton returned home in 1615 (the next year he was appointed ambassador to the Netherlands), Dering decided not to return to England, but rather look for employment on the continent. In 1617 he took up the position of organist to a community of English Benedictine nuns at the Convent of Our Lady of the Assumption in Brussels. In 1625 Charles I married the Catholic Henrietta Maria, the youngest daughter of Henry IV of France, and Dering returned to England to serve in her private chapel as organist.

From a musical angle the two composers have in common that they mixed the traditional English style – still very much the stile antico – with the latest fashions coming from Italy. They treated the latter in somewhat different ways, due to the time they were in Italy. Philips was there in the 1580s, which was the time the stile antico was still dominant. He was especially influenced by the madrigals of Luca Marenzio, and this had its effect on the way he connected text and music. In Rome he also became acquainted with the polychoral style which was practised there, and this resulted in a number of motets for eight voices in two choirs. Dering was in Rome at a much later time, when the seconda pratica had already established itself. This left its mark in his oeuvre, in that the vocal music he published in Brussels includes a basso continuo part. Many of his motets also show the influence of the declamatory style that was one of the hallmarks of the new fashion.

The pieces selected for the present recording attest to the various features just mentioned. The Italian sense for contrast and drama comes to the fore, for instance, in Dering’s setting of Factum est silentium, a motet for St Michael’s Day, which starts quietly, depicting the peace and quiet in heaven. Then the voices exclaim that the dragon fought with the archangel Michael. In Christus resurgens by Philips, the contrast between the first section and the opening phrase of the second, referring to Christ’s dying for our sins and set for the low voices, is emphasized in that the Alleluia, which traditionally closes the first section, is omitted. In his setting of the Salve Regina we notice some of the traits that would become the hallmark of baroque settings of later times, such as the use of sighing figures and pauses. Dering’s Jesu dulcedo cordium is an example of the influence of the modern declamatory style that was one of the features of the Italian monody. He employs antiphonal effects in the closing episodes of his Christmas motet Quem vidistis pastores.

The ‘continental’ traits in the oeuvre of these two composers are emphasized in this recording through the participation of instruments, playing colla voce. In a few cases the cornett substitutes for the upper voice. The instrumentalists also perform four instrumental pieces, among them the Pavan and Galliard Dolorosa by Philips, originally conceived as a keyboard work, but performed here in the way of a piece for ‘broken consort’. It works rather well.

It is quite surprising that the works of these two composers, although quite large in number, are not that often performed and recorded. That certainly goes for Dering, who is not that well represented on disc. However, even Philips is mainly known for his keyboard works, which are frequently played, whereas his vocal music is not that often performed and recorded. It is not that their works lack quality – on the contrary. This disc shows that there is much to discover, and the juxtaposition of the two styles of their time is particularly interesting.

This disc is a most welcome contribution to the acquaintance of their sacred oeuvre. The Choir of Gonville & Caius College has performed and recorded early music in the past, under its then director Geoffrey Webber. This is the first time a recording under Matthew Martin has crossed my path, and I like what I have heard. With its 24 voices it is larger than what may have been the standard at the time (although it is hard to prove how many singers were involved in performances at the time). Historical considerations apart, I feel that with a smaller ensemble the features mentioned above, especially the declamatory features, would have come off better than with a ‘chamber choir’ formation. A smaller ensemble would also have resulted in a stronger presence of the instruments. That said, I admire the way these motets are performed here, given the size of the ensemble.

Taking all things into consideration, this is a very nice disc, which should convince everyone that both Philips and Dering have something to say and deserve much more attention.

Johan van Veen

www.musica-dei-donum.org

twitter.com/johanvanveen

Help us financially by purchasing from

Contents

Peter Philips (1560/61-1628)

Ecce vicit Leo a 8

Loquebantur variis linguis a 5

Richard Dering (c1580-1630)

Jesu dulcedo cordium a 5

Peter Philips

Pavan and Galliard Dolorosa

Richard Dering

Factum est silentium a 6

Peter Philips

Ave Jesu Christe a 8

Richard Dering

Virgo prudentissima a 6

Peter Philips

Ut re mi fa sol la

Jubilate Deo a 8

Richard Dering

O bone Jesu 5

Peter Philips

Gaudens gaudebo a 8

Richard Dering

Fantasia a 5

Peter Philips

Christus resurgens a 5

Salve Regina a 5

John Dowland (c1563-1626)

Paduan a 4

Richard Dering

Quemvidistis pastores a 6